Contents

Capella Maggiore, Piero della Francesca, The Legend of the True Cross, 1452-1465

Arezzo

San Francesco

|

Contents |

Capella Maggiore, Piero della Francesca, The Legend of the True Cross, 1452-1465 |

Piero

della Francesca

b.

Borgo San Sepolcro 1416, d. Borgo San Sepolcro 1492

Piero was born in Borgo San Sepolcro around 1420. He appears to have studied art in Florence, but his career was spent in other cities, among them Rome, Urbino, Ferrara, Rimini, and Arezzo. He was strongly influenced by Masaccio and Domenico Veneziano. His solid, rounded figures are derived from Masaccio, while from Domenico he absorbed a predilection for delicate colors and scenes bathed in cool, clear daylight. To these influences he added an innate sense of order and clarity. He wrote treatises on solid geometry and on perspective, and his works reflect these interests. He conceived of the human figure as a volume in space, and the outlines of his subjects have the grace, abstraction, and precision of geometric drawings.

Almost all of Piero's works are religious in nature-primarily altarpieces and church frescoes-although his serene and noble double portrait Federigo da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza (1465, Uffizi, Florence) is one of his most famous works. The undisputed high point of his career was the series of large frescoes Legend of the True Cross, (1452?-1465?), done for the Church of San Francesco in Arezzo, in which he presents scenes of astonishing beauty, with silent, stately figures fixed in clear, crystalline space. These frescoes are characterized by broad contrasts-both in subject matter and in treatment-that create a powerful effect of grandeur. Thus, for example, the nudes in Death of Adam are contrasted to the sumptuously attired figures in Solomon and Sheba, the bright daylight of Victory of Constantine with the gloom of Dream of Constantine (one of the first night scenes in Western art). In addition, each fresco is organized in two sections-a square paired with a longer rectangle-which he exploits to create a marked sense of rhythm.

Piero's later works show the probable influence of Flemish art, which he assimilated without betraying his own monumental style. In works such as the Sinigallia Madonna (1470?, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino), he adapted to his own purposes an attention to detail and a meticulous treatment of still life that were characteristic of Flemish art. Certain aspects of Piero's work were significant for the northern Italian painters Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini, as well as for the later Raphael, but his art was in general too individual and self-contained to influence strongly the mainstream of Florentine art. He died in Borgo San Sepolcro on July 5, 1492.

The Legend of the True Cross

1452-1465

The Chapel

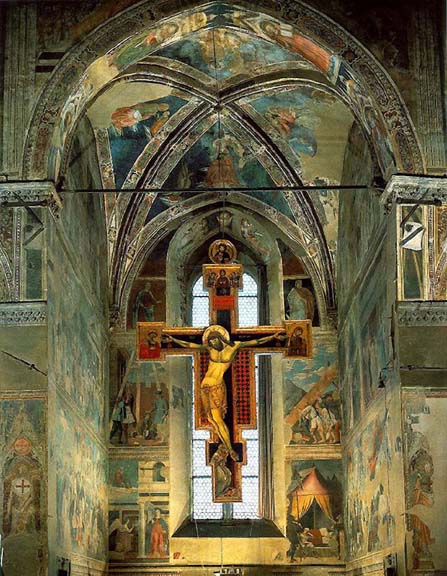

The work on a fresco cycle in the Cappella Maggiore of the church San Francesco had already begun in 1452 when Piero della Francesca visited the city. The Florentine painter Bicci di Lorenzo was working in the chapel, he died in 1452, leaving the decoration of the chapel barely begun. Piero probably began to work right after Bicci's death, covering in a few years the walls of the Gothic chapel with the most modern and most advanced - in terms of perspective - frescoes that the Italian 15th century could have created.

The 13th century Crucifix with Saint Francis was already in the church when Piero della Francesca frescoed the chapel; it has been recently placed above the main altar.

The Frescoes

The subject-matter of the stories illustrated by Piero is drawn from Jacopo de Voragine's "Golden Legend", a 13th century text that recounts the miraculous story of the wood of Christ's Cross. The story tells how Adam, on his deathbed, sends his son Seth to Archangel Michael, who gives him some seedlings from the tree original sin to be placed in his father's mouth at the moment of his death. The tree that grows on the patriarch's grave is chopped down by King Solomon and its wood, which could not be used for anything else, is thrown across a stream to serve as a bridge. The Queen of Sheba, on her journey to see Solomon and hear his words of wisdom, is about to cross the stream, when by a miracle she learns that the Savior will be crucified on that wood. She kneels in devout adoration. When Solomon discovers the nature of the divine message received by the Queen of Sheba, he orders that the bridge be removed and the wood, which will cause the end of the kingdom of the Jews, be buried. But the wood is found and, after a second premonitory message, becomes the instrument of the Passion. Three centuries later, just before the battle of Ponte Milvio against Maxentius, Emperor Constantine is told in a dream, that he must fight in the name of the Cross to overcome his enemy. After Constantine's victory, his mother Helena travels to Jerusalem to recover the miraculous wood. No one knows where the relic of the Cross is, except a Jew called Judas. Judas is tortured in a well and confesses that he knows the temple where the three crosses of Calvary are hidden. Helena orders that the temple be destroyed; the three crosses are found and the True Cross is recognized because it causes the miraculous resurrection of a dead youth. In the year 615, the Persian Kin Chosroes steals the wood, setting it up as an object of worship. The Eastern Emperor Heraclius wages war on the Persian King and, having defeated him, returns to Jerusalem with the Holy Wood. But a divine power prevents the emperor from making his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. So Heraclius, setting aside all pomp and magnificence, enters the city carrying the Cross in a gesture of humility, following Jesus Christ's example.

The scenes of the cycle are:

1.

Death of Adam

2. Exaltation of the Cross

3. The Queen Sheba

in Adoration of the Wood and the Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of

Sheba

4. Angels

5. Prophets

6. Torture of the Jew

7.

Burial of the Wood

8. Discovery and Proof of the True Cross

9.

Battle between Constantine and Maxentius

10. Constantine's dream

11. Annunciation

12. Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes

Battle between Constantine and Maxentius

1458, Fresco, 322 x 764 cm This episode certainly carried an important idealistic hidden meaning and also touched on contemporary events, at a time when Pius II was planning a crusade against the Turks. All attempts to reconcile the two churches had in fact failed, so that, after the Turkish conquest of Konstantinopolis, the only solution appeared to be to unite all Christians in the struggle against the Infidel.

In Piero's fresco, Constantine's face is a portrait of John VIII Palaeologus, former Eastern Emperor. And just as Constantine had gone into battle, leading his troops carrying the symbol of the Cross, so the modern Emperor can defeat the Infidel by leading all Christian armies into battle. But beyond this symbolism the battle between Constantine and Maxentius is depicted as a splendid parade, from which the crashing of arms has definitely been eliminated. The absence of movement immortalizes the horses with raised hoofs in the act of jumping, the shouting warriors with open mouths, all fixed once again by the unbending rules of construction according to linear perspective. Compared to the Battle of San Romano, painted by Paolo Uccello about twenty years earlier and which was one of the highest achievements of that Florentine pictorial perspective that inspired the young Piero, in the Arezzo fresco there is a totally new depth of space between the figures. A realistic atmosphere, conveyed by the bright lighting, emphasizes the various spatial planes. Within this composition, Piero della Francesca succeeded in reproducing, thanks to his highly refined use of bright colors, all the visual aspects of reality, even the most fleeting and immaterial ones. From the reflections of light on the armor, to the shadows of the horses' hoofs on the ground, to the wide open sky with its spring clouds tossed by the wind, the reality of nature is reproduced exactly, down to its most ephemeral details.

Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes

1460, Fresco, 329 x 747 cm

The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius wages war on the Persian King and, having defeated him, returns to Jerusalem with the Holy Wood. But a divine power prevents the emperor from making his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. So Heraclius, setting aside all pomp and magnificence, enters the city carrying the Cross in a gesture of humility, following Jesus Christ's example.

Burial of the Wood.

1455, Fresco, 356 x 190 cm

At the end wall of the chapel, around the stain-glass window and below the prophets were placed the Burial of the Wood (on the left) and the Torture of the Jew (on the right). These two stories were painted by Piero's main assistant Giovanni da Piamonte.

In the Burial of the Wood, Giovanni da Piemonte's heavy modeling draws the stiff folds of the bearer's garments and their hair, rather mechanically tied in bunches. On the Cross the vein of the wood, like an elegant decorative element, forms a halo above the head of the first bearer, who thus appears as a prefiguration of Christ on the way to Calvary. The sky covers half the surface of the fresco and the irregular white clouds are as though inlaid in the expanse of blue.

Death of Adam

1452, Fresco, 390 x 747 cm

Surrounded by his children, Adam sends Seth to Archangel Michael. In the background we see the meeting between Seth and Michael, while on the left, in the shadow of a huge tree, Adam's body is buried in the presence of his family. By placing all three stages of the story within the same background landscape, Piero is abiding by traditional narrative schemes already used by Masaccio in his fresco of the Tribute Money in the Brancacci Chapel.

Discovery and Proof of the True Cross

1460, Fresco, 356 x 747 cm

This is one of Piero's most complex and monumental compositions. The artist depicts on the left the discovery of the three crosses in a ploughed field, outside the walls of the city of Jerusalem, while on the right, taking place in a street in the city, is the Proof of the True Cross. His great genius which enables him to draw inspiration from the simple world of the countryside, from the sophisticated courtly atmosphere, as well as from the urban structure of cities like Florence or Arezzo, reaches in this fresco the height of its visual variety.

The scene on the left is portrayed as a scene of work in the fields, and his interpretation of man's labors as act of epic heroism is further emphasized by the figures' solemn gestures, immobilized in their ritual toil.

At the end of the hills, bathed in a soft afternoon light, Piero has depicted the city of Jerusalem. It is in fact one of the most unforgettable views of Arezzo, enclosed by its walls, and embellished by its varied colored buildings, from stone gray to brick red. This sense of color, which enabled Piero to convey the different textures of materials, with his use of different tonalities intended to distinguish between seasons and times of day, reaches its height in these frescoes in Arezzo, confirming the break away from contemporary Florentine painting.

To the right, below the temple to Minerva, whose facade in marble of various colors is so similar to buildings designed by Alberti, Empress Helena and her retinue stand around the stretcher where the dead youth lies; suddenly, touched by the Sacred Wood, he is resurrected. The sloping Cross, the foreshortened bust of the youth with his barely visible profile, the semi-circle created by the Helena's ladies-in-waiting, and even the shadows projecting on the ground - every single element is carefully studied in order to build a depth of space which, never before in the history of painting, had been rendered with such strict three-dimensionality.

Adoration of the Holy Wood (left side) and the Meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (right side)

1452,

Fresco, 336 x 747 cm (full painting)

Left side: Behind the

Queen of Sheba, kneeling in adoration, is her retinue of aristocratic

ladies in waiting, with their high foreheads (according to the

fashion of the time) emphasizing the round shape of their heads and

the cylindrical form of the neck. Their velvet cloaks softly envelop

their bodies, reaching all the way to the ground. The almost perfect

regularity of the composition is underlined by the two trees in the

background, whose leaves hover like umbrellas above the two groups of

the women and of the grooms holding the horses. And yet Piero's

constant attention to the regularity of proportions and the

construction according to perspective never gives way to artificially

sophisticated compositions, schematic symmetries or anything forced

Right side: This famous scene takes place within an architectural structure, enlivened by decorations of colored marble. Everything seems created according to architectural principles: even the three ladies standing behind the Queen are placed so as to form a sort of open church apse behind her. There is a real sense of spatial depth between the characters witnessing the event; and their heads, one behind the other, are placed on different planes. This distinction of spatial spaces is emphasized also by the different color tonalities, with which Piero has by this stage in his career entirely replaced his technique of outlining the shapes used in previous frescoes.

There is an overall feeling of solemn rituality, rather like a lay ceremony: from Solomon's priestly gravity to the ladies aristocratic dignity. Each figure, thanks to the slightly lowered viewpoint, becomes more imposing and graceful; Piero even succeeds in making the characteristic figure of the fat courtier on the left, dressed in red, looks dignified.