-

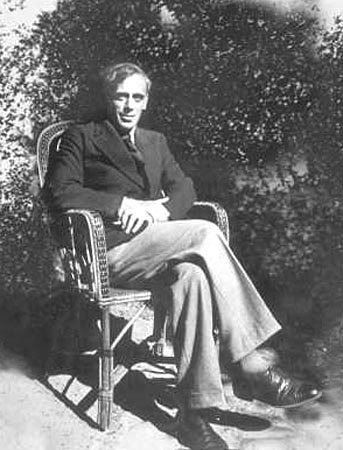

Sergey, Paris, 1930s

Photo dommuseum.ru

France

1925

– 1939

The

Lure of the Motherland

1927

– 1939

Sickly and

unemployed Sergey Efron idled around town. He was never able to hold

down a gainful job. Money simply didn't interest him. For a while he

continued acting as an editor for a Prague émigré

journal. In 1930 he earned himself a certificate as camera man in

film making. Tsvetaeva was proud of him, but nothing came of it.

Towards the end of 1930 he took a job as a physical laborer, but soon

lost that too. Marina rarely mentions Sergey's misfortunes, and

somehow he seems to have been completely indifferent to their

poverty.

|

|

It comes as no surprise

then that Sergey became attracted to various expatriate

organizations: new friends, long political discussions, the lure of

the New Russia. The most important one was the Eurasian

Movement.

The Eurasians rejected Communism but not the Revolution itself. Their

Messianic vision was that an “Eurasian Russia” would

overcome both. When the movement split towards the end of the

twenties, Sergey joined the “left”, pro-Soviet wing. For

a year Sergey was the editor of their journal Eurasia.

Marina

was not unsympathetic to the movement and was friends with several of

its members. The summer of 1930 they spent at a camp of the Eurasians

in the Savoie. At home they had unending, often bitter arguments

about a return to the Motherland. Everyone was for it except Marina.

The Soviet Union had a large number of enthusiastic admirers

among the idealistic, left-wing European intellectuals, especially in

France. Marina describes the ecstatic report of André Malraux

from a visit to Stalin's Moscow. In this intellectual climate the

idea of returning to the Motherland had much popular support among

the Russian expatriats, and the NKVD took advantage of that. They

seem to have infiltrated the left wing of the Eurasians

as

early as 1930. In their Savoie summer camps they supported political

re-education classes. Many Russians left France during the folowing

six years. Those who knew too much were imprisoned or shot on arrival

in Odessa.

|

|

|

Alya had grown up into

a accomplished graphic artitst. Marina spared no money on her

education. Salomeya Andronikova found her a job. In opposition to her

mother Alya drifted more and more towards Sergey's views. In November

1934 Alya (22) and Marina had a fierce argument. Marina finally

slapped Alya for a particularly contemptuous outburst. Sergey in a

furious rage, took Alya's side. [VS

p.320-21].

After this Alya left their apartment. She would be the first who put

her pro-Soviet convictions into practice.

Little is known for

certain of Sergey's being recruited by the NKVD. He did not confide

into Marina, who knew, as a matter of course, of his increasing

radical fanaticism. Viktoria Schweitzer describes an interview with

the daughter of the Bogengardts' [VS

p.328].

She told her of a secretive meeting between Sergey and her father in

1935, in which Sergey confessed his collaboration – Bogengardt

never saw him again. Unsubstantiated rumors in Russia [VB]

accuse Sergey of having actively participated in recruiting for the

NKVD and the Spanish civil war.

Marina bore the role of being

the sole provider of her family. During 1927-1938 she rented one

dismal, cheap apartment after the other in the Meudon area outside of

Paris. So it was a true disaster when the Czech government notified

her in 1929 that her stipend would end, unless she returned to

Prague. After protracted negotiations, friends in Prague persuaded

the authorities to continue paying her 500 kronen per month, half of

the original stipend.[VS

p.286]

Once or twice a month she would give poetry readings, her own

and those of other contemporary Russian writers. These readings were

sometimes arranged by friends. The most generous among them was

Salomeya

Andronikova, a member of an old Georgian noble family, who from

1926 to 1935 sent Tsvetaeva a monthly sum of 300 ffr from her own

pocket and occasionally another 300 ffr that she collected from

friends. To put this sum into perspective, the rent for their

apartment was around 100 ffr. Marina had no compunction to beg for

money. From a note to Salomeya we learn that she asked her to send an

extra 80 ffr for a pair of solid shoes.[VS

p.317].

Salomeya denied her nothing. She gave her clothes and furniture, and

helped to find a publisher for Marina's only book to appear in

France.

From 1923 to 1939 Marina had one close personal

friend in Anna

Tesková in Prague. She shared all her tribulations and

small successes with Anna in uncounted letters, the largest source

for her difficult 14 years in France. These letters affected me very

much. They are of no interest here, but I went through similar

experiences between 1945 and 1951 as the oldest of four siblings in

Germany, although mother was more down to earth and did not write

poetry. A horrible time, unimaginable if one has not gone through

years of hunger, cramped quarters, an emotionally paralyzed father,

and utter poverty.

To keep herself alive Marina still managed

to write, mostly at night. A list of her poems and prose writings

from these years can be found under Sources

and References. After the large Prague Poema

she

wrote predominantly prose. She published her poems of 1922-1925 in

book form, After

Russia, (1927) with

Salomeya Andronikova's financial help. Even the small edition of 500

copies that were printed of the book did not sell. During 1932 –

1939 she wrote four poem cycles: Poems

to a Son (1932), Poems

to an Orphan (1936), Desk

(1937), and Poems

to the Czechens (1938/39)

and a few single poems. She complains many times to Teskova that

taking care of her daily family chores did not leave her enough room

to jot down the lines that passed her mind. Besides nobody wanted to

print her poems – the book had shown that they were unsaleable.

The

first two cycles circle around Russia: the burning question of “to

return or not to return.” When she wrote “Poems to a

Son”, Mur was seven, even in Marina's eyes an unruly,

rebellious child. He was too young to understand Marina's agonies.

The poem must, therefore, have been directed equally at her other,

grown-up “boy”, Sergey, who had spent eight months during

1931 in a Red-Cross sanatorium in the Haut Savoie, because of his

tuberculosis.

|

Стихи

к сыну |

Poems to a

Son |

“Everybody in the

family pressures me to return to Russia,” Marina wrote to Anna

Teskova, “I cannot go.” A few months later Sergey must

have made up his mind. He applied for a Soviet passport. His

application was rejected. He had to “earn” it first.

Marina never mentioned any of this to Teskova; she may not have known

of Sergey's involvement with the NKVD, besides mentioning it would

have been dangerous.

For a while Marina translated Russian

poetry into French, her own and Pushkin, in the desparate hope of

earning some money. After weeks of laboring she admited to Teskova

that her efforts were dissatisfying, especially her work on her own

poems. Then she tried to write poetry directly in French. A few of

those have suvived: “Florentine Nights”, “Letter to

an Amazon,” “Miracle with Horses,” (all 1932). In a

letter to Rilke (July 26, 1926) she had characterized the three

languages at her disposal: “...French is,

an ungrateful language

for poets...”. Her French poems are dry, cold, - in short

“soulless”.

How much she longed for the love a

kindred man who could follow her poetic flights! Pasternak was too

distracted by his disintegrating marriage and moreover was terrified

of the authorities. Their correspondence never rekindled. And then

came the “catastroph”: Boris divorced his wife (1931) and

fell in love with a woman friend of theirs who was already married.

Marina was indignant and irate. “Zhenya (his wife) was there

before me, but to love another – no way! Boris is incapable of

loving. For him love – is suffering. I am not jealous. I no

longer feel any acute pain – only emptiness.” She writes

to Anna Teskova.

In June 1935 Pasternak was obliged by Stalin

to attend the “International Congress of Writers in Defence of

Culture” - ten days in Paris! Marina seems to have avoided him,

and he ran scared of the political watchdog who headed the Soviet

delegation. Rumors have it that he “saw” her in a

corridor of his hotel. He is supposed to have whispered: “Marina,

don't return to Russia, it's cold there, there's a constant draught.”

- Marina wrote Anna, “It was a non-meeting...” - and left

for the sea-shore with a sick Mur (he had had his appendix

removed).

Her Тоска,

nostalgia, homesickness for the Motherland was different from Alya's

and Sergey's. She had few illusions. The Russia she loved and longed

for was gone, the house on Tryokhprudny

Lane had

been razed and replaced by a shoddy apartment building. The people

she loved had left, were alienated, or dead. She carried her Russia

in her soul. For her there was nothing to be found in the new

“Rodina”. In 1934 she wrote a poem that expressed her

loss:

|

Тоска

по родине! Мне

все равно,

каких среди |

Homesick

for the Motherland. |

A year later she expressed her aversion even more vehemently:

|

Никому

не отмстила

и не отмщу

-- |

I

never revenged and never will avenge myself- |

In the hope that prose would be more acceptable and bring in better money, she wrote a number of articles. Some of her pieces were printed in various journals. But the life span of the journals was ususally short, and often enough her honorarium vanished with their demise. Her prose pieces are peculiar: sharply voiced opinions, mostly unpopular ones, alternate with lyrical evocations of an equally personal quality. They invariably made her more enemies in émigré circles than friends. A list linked to the originals is found in my Sources and References.

|

|

|

Photos dommuseum.ru

Alya, encouraged by her

fanatic father, became determined to return to the USSR. “What

can they do to me? I am innocent. Your dark tales are only

anti-Soviet propaganda.” Recalcitrant as she was, with her 25

years she needed to assert herself and break free of her unyielding

mother. She had no problem in obtaining a Soviet passport, they

needed people like her. She left in March 1937, seen off by a

cheerful group of friends and well-wishers. Only Marina was full of

dark premonitions.

The following twenty-four months of

1937-1939 are a blur, a single catastrophe. Marina's letters and

notes give no indication of what happened between her and Sergey. All

evidence is based on unsubstantiated hearsay and rumors. Viktoria

Schweitzer [VS

p.337]

tried to reconstruct that period. She doubts that Marina knew

anything, but feels certain that in the very end Sergey and she

talked.

On September 4, 1937 Ignaty Reyss, a Soviet agent who

refused return to the USSR, was murdered in Switzerland. Efron was

accused by the Swiss and French police to have been instrumental in

shadowing Reyss. It later emerged that he had also been involved in

tracking down Trotsky's son, L.

Sedov. Efron was interrogated by the French police. After the

first interrogation Efron disappeared. Apparently he was spirited by

the NKVD to the USSR. He had no choice, they held Alya as a

hostage.

A bizarre account of the details of his disappearance

appeared in the Parisian emigrant newspaper Renaissance

on October 29, 1937

[Sergey disappeared on 29 September 1937]. According to this article

Marina and Mur were in the Russian embassy car with Sergey that was

taking them to Le Havre. Near Rouen Sergey jumped from the car and

fled. The Russian agents must have caught him quickly. He did not

return. [VS

p.337] - The immediate result of this was that everyone avoided

contact with Marina.

A few weeks later Marina was interrogated

by the French police. She is supposed to have told them, “Efron's

trust may have been abused. My trust in him remains unchanged.”

She read them translations of her prose writings to show her

innocence. Apparently she convinced the police that she knew nothing.

Marina was cleared and let go.

But there was, of course, no

chance that she and Mur could remain in France. The question of her

return to the motherland had been decided for her. She was a possibly

dangerous witness. Two members of her family were practically under

house arrest in the USSR. The NKVD, barely veiled, pressured her to

return and even gave her a small allowance during the summer. After

Sergey's disappearance she and Mur lived in the small Hotel Inova in

Paris. She dedicated her last poem cycle, Poems

to the Czechs, Стихи к Чехии

(1938-39), to the sufferings of Bohemia before and during the German

invasion in March 1939. Hurriedly she distributed her manuscripts

among friends in France and Switzerland. She visited and arranged for

up-keep of the graves of the Efrons in Paris, Sergey's parents and

brother.

Their final departure was delayed for three days.

The Soviet embassy needed to make sure nobody interfered or saw her

off. She wrote a last letter to Anna

Teskova standing on the train to Le Havre. They left Le Havre on

June 12, 1939

A last stanza from her Poems

to an Orphan - Стихи о сироте

|

7. |

7. |

+

+ +