The Stones of Greece

The

Cycladic Islands

Google-Map

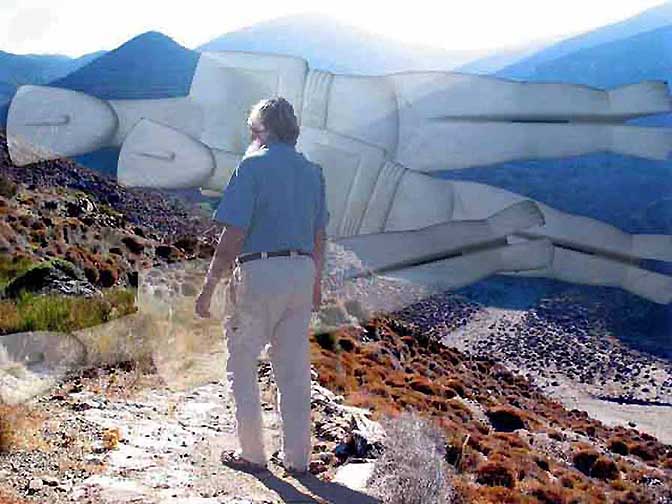

This last section is an indulgence on my part. The Cycladic Goddessess have beguiled me for decades. Barbara even gave me a one from Amorgos - a beautful museum copy - for my 60th birthday.... However, I have never taken the time to trace the Cycladic cemeteries where they come from, excavated and looted. “Oh,” said our host in Amorgos, “what do you want, a koukla (doll)? I know a couple of places where there are some.” But he would not tell me where. So we set out on our own.

In search of Dokathismata on Amorgos, October, 2005

But the Goddess confused all my topographical senses, and we never found the place. Moreover, next day she sent me a serious pleurisy; we had to end our vacation and fly home. - Our last visit to Greece....

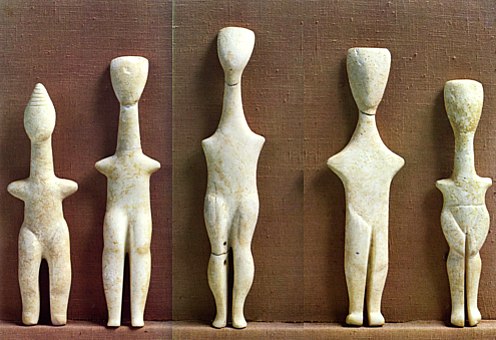

In the summer of 2011 I began to map the archeological sites on the Cyclades Islands and to unravel this confusing field. 2000 years, from the late Neolithic to High Minoan era: a female civilization under the reign of the Great Goddess. The finds are all from necropolis: the Goddess appears only as guide to the Other World, in endless stylistic variations - but, considering the time span, with little change of her abstract form. A sacred image, like her successor the icon of the Greek Panagia....

Like classical Greek marble sculptures, these images were painted – probably in - for us – shocking colors.

The figures in our museums are overwhelmingly undocumented artifacts that have been looted from graves. Until the beginning of the 20th century existed no interest or understanding of such “primitive”, abstract art. They were called “Cycladic Idols”. In the past 60 years a systematic archeological search of the Aegean has produced new locations and objects. It has even become possible to assign groups of sculptures to a dozen individual “masters” on stylistic grounds (Getz-Preziosi) . - Their confusing multiplicity can now be explained by the individualities of their sculptors, a startlingly modern thought.

This brief collection makes no claim to completeness; it is primarily concerned with finding the best photographs of the sculptures, reporting the latest discoveries, and locating the cemeteries on the Google Map. There exists no consistent monograph on the subject, which is up to date.

References and articles in the internet are few and they are often out of date by newer research: here are some worth looking at

History of the Cycladic Civilisation, (4000 BC –2006 AD!),

Wikipedia

Aegean

Prehistoric Archeology, General Chronology Dartmouth

Novoi

Gerodot, a large collection of relevant images (in Russian)

Gerodot.ru

Christos G. Doumas, “Early Cycladic Culture, The N.P.

Goulandris Collection,” N.P. Goulandris Foundation-Museum of

Cycladic Art, Atens, 2000

Pat Getz-Preziosi, “Sculptors of the

Cyclades: Individual and Tradition in the Third Millenium BC,” U of

Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1987

Peggy Sotirakopoulou, “The Keros

Hoard, Myth or Reality?”, J.P. Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2006,

partial view: Google

Books

Marija Gimbutas, “The Goddesses and Gods of Old

Europe, 6500-3500 BC,” U of California Press, 1982

Rolf Gross, August, 2012.

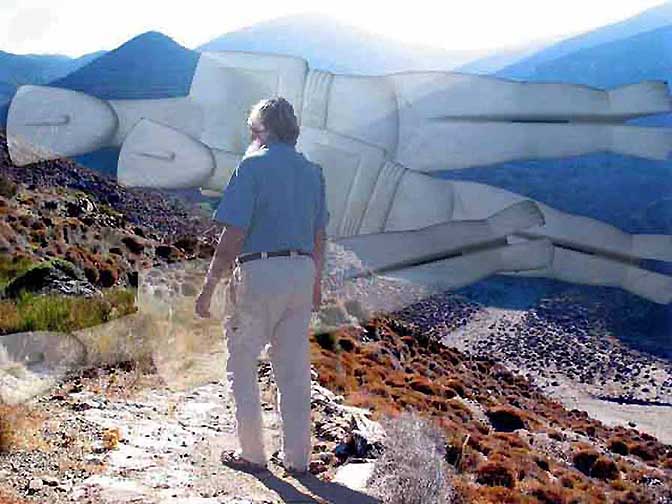

Chronology of the Cycladic Figurines

From

brown

university.edu

The Cycladic culture lasted 1200 years between 3200 and 2000

BC.

These dates are not based on C-14 nor are they

dendrochronologically calibrated. Marble has no C-14 signature. The

chronology was originally based on stylistic typification and that

offers - as we shall see in this case - no systematic, rationally

arguable historical sequence. The idea of attributing differences in

style and form to individual “Masters” is about the only way out

of this dilemma.

About 80% of the material comes from

unscientific digs – I.e. was looted - and consequentially, the

origins of individual artifacts are likewise mostly unknown.

Less

than 5% of the figurines are male – often imprecisely modeled - all

others are clearly marked as female (hips, breasts, pubic

triangles)

All figures and in fact all Cycladic objects were found

in cemeteries (graves). No shrines and very few settlements have been

excavated. Exceptions are Maroulas, Saliagos, Grotta, Daskaleio,

Phyliakopi.

Consequently we know very little about the daily

lives, society, and beliefs of these people.

We do know that men

made the sculptures and certain marble containers, played flutes and

harps (lyres), - hunted, thought deeply, horsed around, and

drank....

Except for the violin-shaped female form which together

with the belief in a “Great Goddess” is Neolithic - the Cycladic

culture has no demonstrable antecedents or, for that matter,

descendants. On the mainland the marble figures were imitated for a

while. In the islands the Minoan-Mycenean civilisation preserves no

memory of the Cycladic forms, of its marble sculptures, or of its

grave culture. The marble objects of Classical Greece, two-thousand

years later are completely new inventions.

The Cycladic culture

vanished from the historical horizon around 2000 BC. We don't really

know why. - It did not touch our consciousness until the 20th century

AD!

A strange phenomenon.

The First Mesolithic Settlements

in the Cyclades

7500-6000

BC

During the Paleolithic and Mesolithic periods people were hunters and fishermen who lived in caves: Franchthi Cave (20 000-3000 BC), Cyclops Cave on Gioura Island (7000-4000 BC). Apparently they were able to sail and conduct business across the Aegean Sea at least as far as Milos and the Anatolian coast. The oldest surface settlement (7500-7000 BC) in the islands recently excavated (2005) is the Mesolithic village of Maroulas on Kythnos. The Mesolithic was “aceramic”. Pottery, ceramics and, sculptures appeared only in the late Neolithic after 5000 BC in the Islands.

Kythnos,

Maroulas

7500-7000 BC[?] Mesolithic

The site at Maroulas on Kythnos appears to be contemporaneous with the Franchthi Cave in the Peloponnese and the Cyclops Cave on Gioura Island. The settlement constitutes the first Mesolithic open-air site with architectural remains in Greece and specifically in the Aegean.

Excavation at the site of Maroulas near Loutra, were initiated in 1996 by Sampson and continued in 2001 by the University of the Aegean in collaboration with the Cyclades Ephorate of Antiquities and the University of Krakovia (Krakow, Poland).

Excavation continued till 2005 and revealed more than 30 circular structures. The building technique of these constructions comprised numerous slabs as well as intermediate fillings with small stones. Without a doubt,these were the paved floors of shacks. Moreover, two semi-subterranean circular constructions were excavated inside natural rock-cavities. They preserved a number of successive floors, where food residues and layers of burning were found in situ.

Fifteen human skeletons in the characteristic “cross-legged” position were recovered under the floors of the circular constructions.The dead used to be placed inside a rock-cut cavity or a pit, either slab- or stone-lined, and finally covered with large slabs. Under the floors were also found secondary burials (skulls or parts of skulls).

All these elements refer to a Mesolithic

pattern also found in the Cyclops Cave on Gioura.

Chronologically the settlement was determined by three

(un?)calibrated C-14 dates between 8800 and 8600 BC.

Text quoted

from scrbd.com

Comment by RWFG: The (raw) C-14 dates are certainly too early, This excavation site is not mentioned elsewhere in the internet literature. Archeologists are jealous people and Krakow University & the University of the Aegean are no powerful credentials.

Late Neolithic/Early Cycladic EC

I

4500–4000

BC

Saliagos Island

Saliagos, a tiny, uninhabited island between Paros and Antiparos is

one of oldest documented sedentary settlements in the Cycladic

Islands. It was excavated by the British Archeological Institute in

Athens between 1964 and 1965. Estimates based on excavations in the

cemetery of Kephala put the number of inhabitants at between

forty-five and eighty. Studies of skeletons have revealed bone

deformations, especially in the vertebrae. They have been attributed

to osteoporosis, a sign of a sedentary lifestyle, but this affliction

is rarer than on the continent in the same period. Life expectancy

has been estimated at twenty years, with maximum ages reaching

twenty-eight to thirty. Women tended to live less long than

men.

Wikipedia

On Saliagos (which in the neolithic was connected to Antiparos), houses of stone without mortar have been found, as well as several Cycladic statuettes: among them a small, early violin-shaped and a sitting, steatopygous representation of a woman.

|

|

|

This Violin-shaped figure (c.4500 BC) is the earliest of this type

that has been documented. This late Neolithic figure has a flat

appearance and a frontal mien similar to that of the Violin figures

of the later EC I period. It has more naturalistic qualities

than the later examples indicated by the comparatively curvaceous

lines. However, this does not detract from the evident geometrical

form that make up this and later Violin figures. In this example, the

head is identified with great economy by a notch at the top of the

elongated, cone shaped neck which itself, almost appears to be an

extension or continuation of the body. Two triangular shapes protrude

to indicate the arms and then two more, identifying the legs in their

crossed pose.

Text and photos Michael

Michaelis

Early Cycladic EC I

Violin-shaped

Figures

3000-2800

BC

Naxos: Akrotiri, Sangri

Antiparos,

Schinousa

|

|

|

Early

Cycladic EC I,

Plastiras Figures

2800-2600

BC

Paros: Plastiras, Glypha, Dryos, Pyrgos

Naxos:

Akrotiri, Sangri,

Keros, Antiparos, Amorgos, Delos, Thera

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

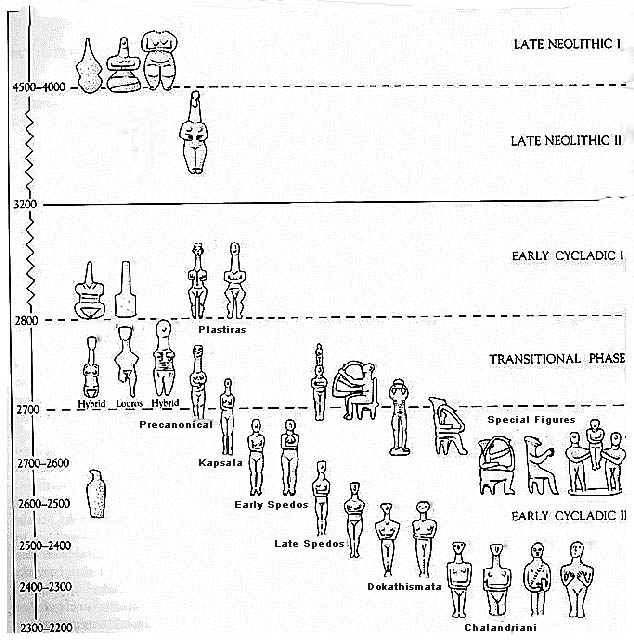

Early Cycladic EC II

Kapsala Figures

2700-2600 BC

Amorgos: Kapsala

Naxos: Aplomata,

Keros: Kavos, Daskaleio

These two figures are the first Cycladic marbles found, excavated by the German archeologist Ulrich Köhler (1838-1903) in one grave on Keros in the 1880s.

The

Hunter and his wife

Early

Cycladic II (2800-2300), Naxos-Spedos?

(l.) Nat. Archeol.

Mus., (r.) Goulandris Mus.,Athens

(seltisa.gr)

These are almost all representations of men among the hundreds of female sculptures from the islands. It seems obvious that the sculptors were men. There exist at least 6 harp players (Metropolitan, Getty, Badisches Mus, Nat. Archeo.Mus, a pair in a priv.Collection), two flutists, one damaged thinker, one drinker, and two or three hunters. – All from EC II around 2500 BC, all pensive or troubled self-portraits of men. The lives of the men in this “matriarchal” culture must have been difficult. This hypothesis cannot be proven, but it is supported by the objects excavated in the surrounding areas, the Balkans, Moldavia, Romania, Ukraine, and Cyprus (Gimbutas 1982). And of course, by the classical Greek myths, which describe the transition from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society (Theseus, Orestes, Medea, etc.)

Early

Cycladic Transitional EC I/ EC II

Louros

Figures

2800-2750

BC

Naxos: Louros Cemetery

Paros:

Dryos

Two

typical Louros figures, (Michaels)

After the “Baroque” Plastiras phase, which seems as if the Cycladic sculptors would continue making ever more realistic marbles, one courageous man began to shape them in most abstract forms. Of course, these figures can be considered to be a return to the violine shape, but their lucidity and spiritual radiance are far beyond the modified beach pebbles. Estheticaly and artistically they are a new stage in the development of the Cycladic mables.

Other

figures from Louros grave 26,

Stephanos Master, Nat.Arch.Mus.

Athens

(gerodot.ru)

Getz-Preciosi assigns them to the “Stephanos Master”, the name of the discoverer of the Louros site in central Naxos, but - like other students of Cycladic sculpture - she expends few words on them – an atavism...

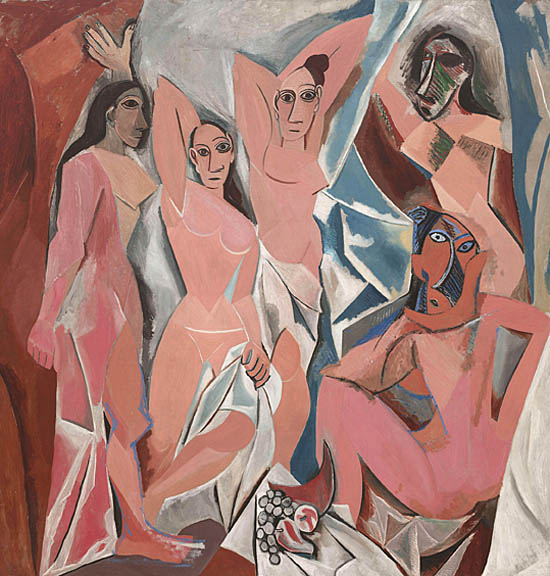

I am reminded of Picasso's Ladies of Avignon, who at the beginning of the 20th century revolutionized painting for the next 100 years.

Pablo

Picasso, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 AD

MOMA, New York,

(Wikipedia)

Early Cycladic EC II

Early

Spedos

2600-2500 BC

Naxos: Spedos, Aplomata

Les

Déesses d'Aplomata

EC II, Early Spedos ~2500 BC (Wikispaces)

During the Early Cycladic II period, the number of cemeteries

increased and each tended to have more graves and burials, reflecting

a rise in population and possibly a different organization of

society. The establishment of new burial grounds close to the sea

seems to suggest a shift to coastal, nucleated communities. While

cist-graves remained in use, their size and design was altered

slightly to accommodate multiple burials. The graves became deeper

and included a small platform separating the latest burial; earlier

burials were stored underneath the platform. Goods included marble

vessels and figurines, silver and bronze jewellery, cosmetic items,

beads of shell and stone, and pottery. Bronze weapons appear in a

very small number of graves. As in the earlier phase, there is

considerable variation in the quantity and quality of grave goods

(while many graves had no goods at all), reflecting a society of

varying wealth and status.

Goulandris

Museum

|

|

|

The Pregnant Goddess, 30 cm, Early Spedos EC II, provenance unknown

(collect. Waltz)

(Gorney

& Mosch, Munich)

The Cycladic sculptor had one advantage over Picasso, his Goddess was allowed to be pregnant resulting in some of the most touching images.

Early

Spedos, 132 cm, provenance unknown

private collection, Belgium,

not attributed to any master (Getz-Preciosi,

Plate X)

One of the largest complete Cycladic sculptures yet found. The piece is remarkable for its workmanship, surface finish and preservation.

Early Cycladic EC II

Late

Spedos

2500-2400 BC

Naxos: Spedos

|

|

|

Two excellently preserved works of the Goulandris Master (Getz-Preciosi, Plate IX) the most prolific sculptor of the canonical folded-arm figures displaying a calm force, a harmony of proportions, and refinement of lines.

Early Cycladic EC II

Dokathismata

2400-2300

BC

Amorgos: Dokathismata

Donousa, Kouphonisi

Dokathismata, EC II. 39 cm, from Keros(?)

Goulandris Mus. #206,

Ashmolean Master

(Panoramio)

Dokathismata, EC II. 2400-2200 BC, 27 cm, provenance.unknown

National

Archeo. Museum, Athens

Berlin Master

(greek-thesaurus)

Amorgos is a rocky, infertile island which does not produce suitable marble or could feed a large sedentary population. The master sculptors who produced these two elegant statuettes probably worked on Naxos and the figures were imported to Amorgos. During the third millenium Amorgos – the eastern-most island of the Cyclades – must have lived of the lively trade between the Clyclades and Anatolia. Its ship owners were rich just like today.

Early Cycladic EC II

Chalandriani

2300-2200 BC

Syros:Chalandriani

Chalandriani

Figure, 14 cm

2300-2200 BC, Goulandris Museum

Dresden

Master

(mfa.online)

By the 22nd century BC the Cycladic marble masters had exhausted their artistic resources. The figures decline and are eventually replaced by Minoan painted clay figurines. A natural disaster, like the explosion of the Thera volcano in 2100 BC, may have contributed to the demise of this culture, as may have the arrival of the Minoan people from the Hear East. As long as there exist no excavations of settlements in the Islands from between 2500 and 2000 BC, we will not know.

At this period, a new type of corbelled tomb emerged at the extensive

Chalandriani cemetery on Syros. In a corbelled tomb, the roughly

circular walls were made of courses of dry masonry decreasing in

diameter until only one slab was needed to seal the tomb. Although

the Chalandriani tombs were provided with side entrances, they mostly

held single burials. More than 600 graves have been found, clustered

in distinct groups; there is considerable diversity in the quantity

and quality of grave goods.

Goulandris

Museum

Sold

as Chalandriani Figure,

20cm, provenance unkown, chipped

shoulder

right arm above left!

Christy

Auction 2000

“Frying

Pan” from Syros, 2700 BC, Wikipedia

Frying pans are ceramic objects of unknown purpose from the archaeological strata called Early Cycladic II in the Aegean Islands and the Early Helladic I and II elsewhere in the Aegean. There has been much speculation over the mysterious purpose of what must have been prestige goods. Characteristically highly decorated, much care has gone into their making. They have been found at sites throughout the Aegean but are not common: around 200 have been unearthed to date. They are usually found in graves, although they are very uncommon grave goods; their rarity does not help to indicate their specific purpose.

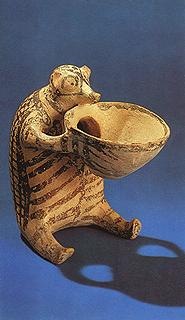

Chalandriani

Hedgehog bowl

Early Cycladic EC III

Phylakopi I

2300-1100 BC

Milos: Phylakopi

The

Lady from Phylakopi

Late Cycladic III, (1550-1100 BC)

(chronos)

In the Early Cycladic III period, many cemeteries were abandoned and

this has been thought to reflect a decrease in population. However,

it is also possible that this phenomenon indicates a shift of

occupation towards coastal urban centers, such as Phylakopi on Melos,

Paroikia on Paros and possibly Ag. Irini on Keos, Akrotiri on Thera

and Grotta on Naxos (although the corresponding levels of the latter

settlements are rather insufficiently explored, so far). Our

knowledge of EC III burial customs is very limited, since only a few

cemeteries of this period have been excavated. We do know, however,

that the Cycladic people continued to use cist graves, but the

rock-cut tomb also emerged during this period to accommodate multiple

burials. The few excavated tombs and cemeteries have included more

decorated pottery than earlier periods but very few items of other

materials.

Goulandris

Museum

Phylakopi (Greek=Φυλακωπή), located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its almost continuous inhabitance throughout the Bronze Age (i.e. from the early 3rd millennium BC until the 12th century BC), and in plentiful architectural and artistic findings; Phylakopi is an important site for understanding the development of the prehistoric Cycladic culture.

The excavations of the British School at Athens from 1896 to 1899 showed the continuity of life from the 3rd millennium BC to the late 2nd millennium BC, in three main phases. At the first phase (2300-2000 BC), the houses of the settlement were small, made of makeshift materials without squared rooms and without walls.

During the second phase (2000-1550 BC) the houses were made of stone with right angles, and in several instances they had a second floor. The walls are decorated with frescoes of flowers, birds and human performances. The relations with Minoan Crete were very close during this period. Perhaps Phylakopi was a Minoan settlement. Findings such as the fresco with flying fish (National Archaeological Museum of Athens, illustration) and the cylindrical vase stand with the representation of fishermen holding fishes indicate strong Cretan influence, or have been created by craftsmen from Crete. Plenty of Cretan vases have been found from the so-called "Kamares style" pottery. The city at that time was protected by strong walls.

In the third phase (1550-1100 BC) the city was at its largest and was protected by strong fortification. The roads converged at right angles. The settlement in this phase lived under the strong influence of the Mycenaean civilization on the Greek mainland. A Mycenaean palace was found at the northeast area of the town. The tombs are carved in the rock, consisting of one or two cells. Such tombs were found in Phylakopi, in Zephyria and in cape Spathi in the north-east of the island.

At the end of the Bronze Age, the city of Phylakopi was

abandoned.

Wikipedia

A Contemporary Story

The “Keros Hoard”

Early

Cycladic EC II

Early

Spedos

2700-2300

BC

Keros: Kavos, Daskaleio

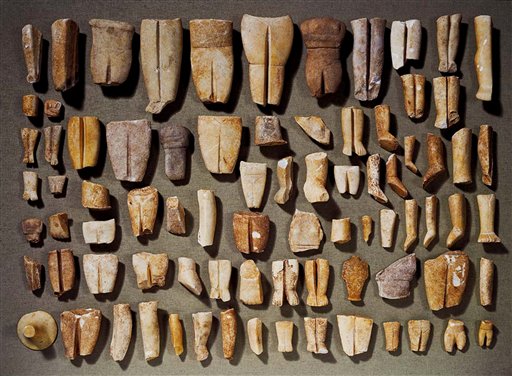

The

Erlenmeyer portion of “The Keros Hoard”, tumblr

In the 1960s, during the height of the archeological interest in Cycladic objects, fragments of broken figures and marble goods began to appear in profusion on the European market. They were supposed to come from Keros Island. Very few complete figures were among them. Only one grave, which had yielded the flute player and the first harpist in 1860, was known on the desolate, uninhabited island.

In the late 1950s C. Doumas had visited the island and found a diffuse area at a location called Kavos, where large quantities of broken pieces could be picked up on the surface. The obvious origin of the looted material. Various archeologists became involved in the mystery of what Pat Getz-Preciosi-Gentle had named the “Keros Hoard”. Meanwhile - the Greek government being unwilling to put a stop to it - the looting from the site continued.

Forty years later Pat Getz-Gentle (2008) would describe how the obejcts had been carried in suitcases to a Greek dealer (Koutoulakis) in Geneva and Paris, who carefully parcelled them out to eager collectors. A large part was acquired by the Erlenmeyer Collection in Basel, which was dispersed after its collector died.

In 1968 Colin Renfrew of the British Archeological School in Athens, visited the site, secided that it was not a cemetery and discovered an EC II settlement on the tiny island of Daskaleio, two-hundred meters from Kavo. Renfrew succeeded to found the Cambridge Keros Project, which persuaded the Greek government to permit a systematic excavation at Kavos and Daskaleio in 2006-2008.

The

Kavos excavation site in the fore-, Daskaleio Island in the

background, Times

At first Renfrew's finds only deepened the mystery: He found several shallow “dumps”, the trenches barely visible in the photo, with thousands of “discarded” pieces but no traces of human graves. Morever the sculptures had been broken in the 3rd millenium before they were brought to Keros from all over the islands. The excavation of Daskaleio revealed a sizable “sanctuary”, which must have been only in seasonal use. The island or Keros could not have supported a commensurate population year round.

Renfrew finally proposed that the site was the sacred depository of sculptures and other ritual marble objects from the Cycladic world. A hypothesis which the profession resisted for a while, despite that deposing holy icons in a precisely determined ritual is practiced in the Greek Orthodox Church to this very day, and Jewish religion knows of a similar depository of sacred texts at the Genizah in Cairo.

In reverse, this discovery shows that the female marble figures found in the Cycladic graves were in fact sacred objects: the Great Goddess as Guide to the Afterlife.