GRIECHENLANDBUCH

For Christmas 1942 my father gave me a book. Its wine-red cardboard binding showed the eagle of the German Air Force, but instead of the usual swastika it held an olive branch in its talons. Below there was the simple title "Griechenlandbuch."

It was a curious find. On immaculate, white paper two young soldiers told the glowing story of their adventures during two months of wandering through the recently subjugated country. They had gone on their journey entirely by themselves, unarmed, in complete disregard of the abundant partisans everywhere.

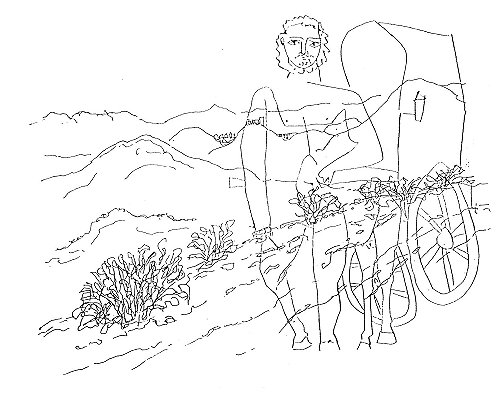

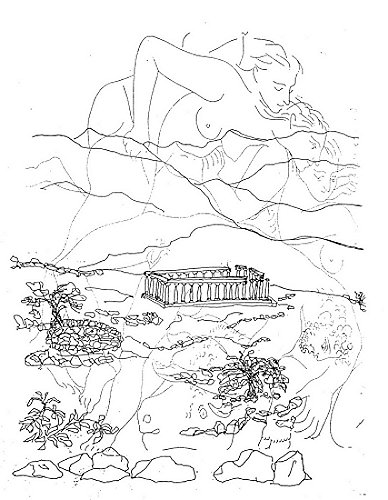

Scattered throughout the text were drawings of the Greek landscape, the old sanctuaries, and occasionally of the people they had seen and met. The drawings had a breathtaking quality, very thin lines barely indicated sea, mountains, olive trees, temple ruins, and Byzantine churches. Nothing was hidden in these transparent drawings, nothing superfluous, no shadows, and above all, behind all, suffusing every object, the light, the merciless fire of the Greek sun.

The text was written by an unknown, Erhard Kästner, the drawings were by Helmut Kaulbach. The commander in chief of the South-West European Air Command had temporarily relieved these two men of their duties and sent them out to write this book to be presented to his soldiers for Christmas. A declaration of love for the defeated country in the middle of a total war, a strange book.

Touched and fascinated by the clarity and light that Kaulbach's drawings promised, I carried this book around with me for the next ten years. It was the only one of my books that I was allowed to take with me, when we were driven from our home in Silesia in 1946. A friend to whom I had lent it in Göttingen, finally lost it.

Kaulbach died in Russia. Kästner wrote a second version of the book after the war, however, he never recovered the innocence of the first.

The fighting in central Europe ended, but the internecine war in Greece raged on well into 1950, tragic and brutal, between friends and brothers, fathers and sons, refugees from Asia Minor and the locals, communists, republicans, and royalists.

In the summer of 1952, in a youth hostel in Florence, my brother Gerhard and I met a couple from New Zealand who had just visited Greece. I will never forget how the vivacious, dark-haired, young woman for a whole evening excitedly described to us the longed-for land. Encouraged, Gerhard and I set out for Greece in the summer of 1953.

We were almost penniless, slept under the stars and lived of bread, olive oil, black coffee, fried eggs, and tomatoes and grapes stolen from the fields along the road. Sometimes we hitched a ride, once or twice the local bus picked us off the street - and to our embarrassment refused our money - but most of the time we went on foot. For three glorious months we hiked through Attika and the Peleponnesos, over the mountains of the Troizenias to Epidauros, across the Argolid to Mycene and Tyrins, from Megalopolis along the valley of the Alpheios to Karytena and Andritsena, and over the wild mountains of Arkadia to Bassai and Olympia. On the 10th of October we sailed from Patras back to Brindisi, steerage, on the old "Kyklades."

We learned Greek from the people we met on the road, in the shops and villages, into whose hospitable houses we were invited, peasants, emigrants, who had returned after a lifetime in America. For the foot-operated drill of a young village dentist we designed a an electric generator, which remained a fantasy, because it was much too expensive. Simple people and highly educated ones, like Nonda Spiliotopoulos, the bored heir to a vast shipping business, who spoke four languages and who - attracted to my innocent brother - spoiled us in his villa in Poros for two whole weeks... They overwhelmed us with their hospitality and charm.

But it was the landscape, the blue sea, the mountains, the uncompromising barreness of this stony land and the light, the terrible light of the Greek sun, which with its magical power for ever altered the pictures of my imagination. Since then I live with and of these pictures, and when Gerhard died I became aware that this "Arcadia" of my memories had turned into an Icon of great power.

I have been back to Greece many times, with Gerhard in 1954 and later with Barbara. But I had never seen the places again that we visited on this first trip. I told myself that I did not want to burden Barbara with these memories, but now I believe that I may have been subconsciously afraid to tempt these strong impressions and possibly lose the images I lived of. How could I expect to ever experience again the high of my 22nd birthday?

Meanwhile, almost 40 years had passed, and I thought that I was old and strong enough to take Barbara to the sacred places of the Peleponnesos, to celebrate my 60th birthday. But I underestimated the forces that are present in these "power spots," as the North American Indians call such places. I was well aware that there are strong subterraneous relationships between Delphi, Bassai, and Dodona or Athens, Epidauros, and Troizen, and Gerhard, who had no sense for such things, ridiculed me all his life long for my "mystical notions." But the dark, chthonic currents that course through this earth, that give the Greek landscape and its very old sacred sites their power, I did not understand then. Nor was I aware that my "Great Icon" derives its power from these very same forces.

Thus it happened that these travels to Arcadia brought a string of most unexpected experiences of the mind. Puzzled, I realized that none of my many travels to other, far away countries, to India, to Tibet, to China had ever tested all my understanding as severely as this land, which I had believed to know so well, whose mentality and myths have been so close to me since my earliest childhood.

The most important insights I gained "cannot be said," as Wittgenstein concludes, one cannot describe them with our normal language. Neither can they be photographed, as I learned to my regret. Such things are invisible to the camera. But I knew from Kaulbach that one can draw them: I set out to redraw Kaulbach's Greece, to search for the transparent clarity in its landscapes and its dazzling light.

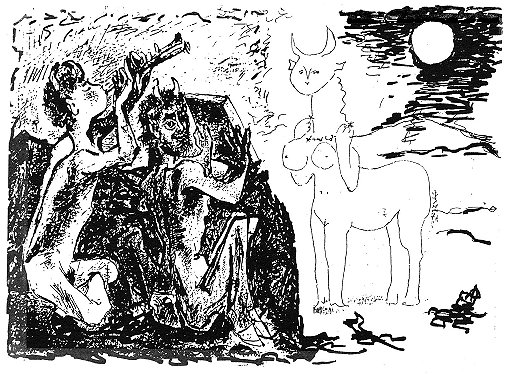

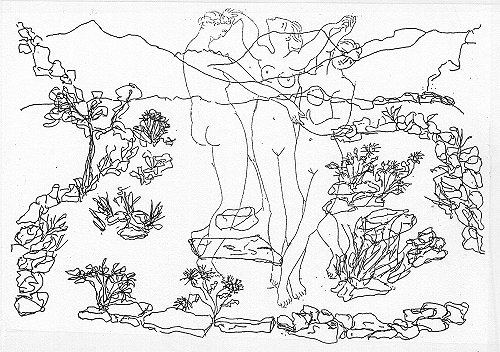

However, how to draw the dark "powers" lurking in and underneath the surface, how to show the age-old myths that give this land its numinosity? After several weeks of contemplating this question, I, one day, rediscovered another old friend in spirit, Picasso. He has never been to Greece, but he knew exactly what I perceived: the gentle, the erotic, and the barbaric aspects of the most human gods that man has ever conceived of, and who, to this day, still very much populate the Greek countryside. I am sure Picasso would have forgiven me my changing, manipulating, and copying his drawings in order to populate my Greek underworld with them. After all, he knew more about their chthonic aspects than I had known.

THE GREAT GODDESS

To Marija

Gimbutas,

hoping that she will allow

a man to persue her

Goddess

I always thought that the numinosity of the number Three was a patriarchal Indo-European invention, a symbol of the male sex. Now I know that the Trinity is female, and that it is much older than the Indo-European migrations. It originally stood for the Triad of the Great Goddess, the three transformational aspects of Woman: virgin, mother, and old crone.

The differentiation of the Goddess into the three distinct, anthropo~morphic aspects of Kore, Demeter, and Hekate is surely a male invention of the later Greek era. Before that no systematic religion existed, and there was only one Great Goddess. Even in classical representations of the fifth century BC Demeter and Kore, mother and daughter, often look so much alike, that they cannot be distinguished without their attributes. Demeter holds an ear of grain and Kore a pomegranate, symbols of golden maturity and budding fertility. But at the same time, the red pomegranate was a symbol of death: those who eat of it, who love and produce seed will die, are claimed by Hades. Just as Kore, having eaten of the pomegranate and been loved by Hades, had turned into Persephone, the queen of the dead, and had disappeared in the underworld.

However, through the entreaties of her unhappy, half crazed mother, Zeus finally permitted Persephone to spend two thirds of the year as Kore among the living. Only winter did she spend in the land of the dead. Thus, she became the personified promise of "resurrection," because in spring time, visible to everybody in the sprouting and greening of the young grain, she returned to begin a new cycle of life.

This many layered myth is confusing and hard for us to grasp, solely because in the meantime we have become used to giving "names" to the "objects" of our subconscious. Our paradigm, invented by the Greeks, is analytic-linear and no longer "synchronistic." But the "atomoi" of the subconscious are truely indivisible, are archetypes which include their contrary, which can be "known," grasped, or seen in toto, but which cannot be described with linear sequences of words and letters.

In the pre-Helladic matriarchy this was much simpler, there were no gods or goddesses, there existed no organized "religion", one "knew" only the one "Great Goddess", who suffused everything, plants, animals, and the earth, and her forms were manifest in the landscape.

During the past eighty years archaeologists have dug up a veritable flood of objects form this "pre-European" period in the South-Western Ukraine, in the Balkans, in Northern Greece. These finds, newly dated, have turned out to be far older than once thought, to belong to the period between 7000 and 1500 BC. Thousands of richly decorated, anthropo~morphic figures, some uncannily "modern" in their abstraction, allow us to draw a believable, if not unanimously accepted, picture of the religious ideas of the agricultural, sedentary matriarchy of Old Europe. Marija Gimbuta's photographs of these sculptures read like a veritable catalogue of the images of our subconscious. Regrettably, C. G. Jung did not live to see these images, they would have lent his theories strong support. They are representations of the Goddess in her varying manifestations. Filled with eggs she appears as the pregnant Goddess. She wore the masks of her sacred animals: bird, dog, frog, bear, or pig. As bee, as chrysalis, or with the Minoan butterfly-ax she pointed at her annual epiphany and rebirth, and in rigor mortis, as flat "marble idol" she accompanied the dead into the graves of the Cycladic Islands.

The overwhelming majority of these figures is female, but there are also a few male figures. They show the man as phallic fertility- or year-god and already in the earliest times, as an immensely sad "thinker," who, his head cradled in his hands, bemoans his sad fate. During matriarchal times the life of a man must have been terrifying. As year god or king of the zodiac he was selected by the queen to share her bed as her spoiled lover, only to be ripped, limb by limb, into bloody pieces by her priestesses after twelve months, at the full moon of the midsummer night. His blood was then poured over the fields to fertilize the new seed. It comes as no surprise that he drank, as a Cycladic version shows him. Later, in the third and second millennium, he invented music to console himself. He learned to play the melancholic harp or the lustful double flute. But of these most beautiful figures of Old Europe, made of wonderful, semi-transparent Parian marble, we only own six or eight pieces, and they were all found on the islands surrounding Amorgos the eastern most neighbor of Thera-Santorini, the superbly sophisticated Island of Atlantis.

However, the greatest manifestation of the Goddess was Gea, the Earth from whose womb all life came and grew and to whose body it returned in order to be revived from the dying seed. She held out the promise of an eternal, cyclical life and, visible to all, her bodyscape showed all the threatening and gentle signs of her female nature. It was possible to touch her, dig in her, sow and reap her, man could wander across her body, and, sheltered between her breasts, he could dwell, sleep, or dream.

And thus already very early in this, her sacred landscape, in the lap of a mountain-fringed megaron, at a spring between her breasts, at the mysterious opening of a dark gorge, or under her tree-hair, man began to build sanctuaries where he venerated the presence of the Goddess. The oldest among these sites are unfortified. Never do they occupy the heights of mountains. Those belonged to her alone. Despite its many stones, the felicitous landscape of Greece is as female as few other on this earth, and across it are strewn innumerable power spots. Those who have a sense for such places, for the powers that dwell in them and for the forces that connect them with each another and the landscape, their powers can still be as tangible today as they were eight thousand years ago.

In the middle of the fifth millennium arrived the first hordes of Indo-European Dorians on their horses from the Russian steppes. Swinging bronze lances and hatchets, they raided the defenseless villages of matriarchy: real men, handsome, blonde, strong heroes. One can follow their recurring waves by the circular graves which they dug for their dead among the rectangular shaft graves of the locals. Their royal graves were filled with weapons and precious gold jewelry. Not everywhere did they destroy the old villages and towns. They found the land fertile and to their liking and often stayed on, shaking the local men out of their resigned stupor, inciting them against the mother queen, and into raping her priestesses. The rapes and the sheer endless bloodshed of those times live on in the Greek heroic myths to this day. Within the next two thousand years matriarchy found its end.

But the women survived, seduced the Heroes with their sensual dark beauty, inherited their female consciousness to the children they bore them, and gave life to their art, their religion, and their fantasies. From this forced hieros gamos of opposites sprang the Greek miracle that defines our life and thinking to this very day. The euphoria of this marriage lasted less than a thousand years until the genetic substance of the conquerors was spent. Then Greece sank back into the nameless chaos in which it existed before the Dorian invasions. Other invaders of the once again defenseless land, Romans, Christians, Turks carried away the last remains of classical Greek culture.

The Great Goddess, however, lives on in our subconscious, in the new gods and even in some of their Christian descendants, in her sacred places and temples, but most of all in the mountains, valleys, springs, and fields of the Greek Earth. And there she is still able to give happiness, peace, and insight to those, who try to understand her age-old being.

Heraion Akraia 15.9.1991

THE HERAION AKRAIA

Almost nobody seems to know the temple of Hera at Cape Melangvi, the Heraion Akraia, "Hera of the Cliffs." It lies a few kilometers west of the village of Perachora, at the outermost tip of the peninsula extending from Mount Geraneia into the Golf north of Korinth.

Together with the Heraion of the Argolid, this is one of the oldest sites in Greece, dating back to the early sixth century BC. And nowhere is the presence of the Great Goddess more evident than here, yet it is a lovely place without the threatening aspects that often haunt her oldest sanctuaries.

In former times the pilgrims must have come from Korinth by boat to land in the small, nearly circular harbor. Today one has to climb down the precipitous cliffs from the road above, facing the blue sea and the few remnants of the sanctuary below, at the water's edge.

However, the signs that show the presence of the Goddess can only be seen, when one finally stands on the foundations of the temple. And they are unmistakable. Two huge horns frame a small megaron with the head of the reclining Goddess marked by a triangular block between them, just as Mount Iouktas appears between the horns of Minos in Knossos, or like the horns and triangles that to this very day protect the churches and doors of the old houses in the Khora of Amorgos. Now, one realizes that the temple lies between the thighs of the Goddess, who is cooling her legs in the sea. Remains of a second temple can be found higher up in a small wood that modestly covers her crotch and the hole of an immense cistern.

We spent a very hot noon there. Trying to cool herself, Barbara swam in the warm, transparent sea. I, however, no friend of unknown waters, slept in the shade of the curly pubic hair of Mother Earth and dreamt of the bull that had one day come across the sea and had scared her maidens away for ever.

Mykenai, The Ravished Goddess 16.9.91

MYKENAI

In Mykenai I am still overcome by dread. The first time Gerhard and I were there, we spent a full-moon night on the roof of the archaeologists' hut. A warm wind blew from the Argolid plain below. One could almost touch the mountains of the inner Peleponnessos across the valley in the silvery light. Late that night an Englishman joined us. None of us could sleep, and thus we began to recite the old horror stories of the end of the Atrides in the bloodbath at Mykenai. We all knew these myths since childhood: The tale of the homecoming of the victorious Agamemnon after the Troian war to meet Klytaimnestra, whom, in an earlier feud, he had raped and taken as his wife, after slaying her husband, his uncle.

Filled with the old hatred for the man who had ravished her, Klytaimnestra together with her lover Aigisthos had plotted her husband's murder. A bath is watiting for the tired victor. As the doomed man steps from his bath, Klytaimnestra throws a net over Agamemnon and helps Aigisthos to cut down the defenseless, naked hero. With the sacred axe of the Goddess, at the last moment, Klytaimnestra castrates him and hacks off the head of the dying man who has fallen into the bathtub. And all who have come with Agamemnon from Troia die at the hands of Aigisthos' men. Swearing the most terrible oaths, Kassandra, the unhappy Troian prophetess, tries to defend the twins she bore Agamemnon. In vain, "men died like pigs at the feast of a king," the epic says. According to Pausanias, they were buried in the great circular grave outside the castle gate - where they were found by Schliemann, eighteen adults and two children. Klytaimnestra, however, profanes the day with celebrations, the day of the full summer moon on which the king must die.

The killing did not end here. Orestes, Agamemnon's and Klytaimnestra's only son, hidden by fate, had survived the slaughter, and seven years later returns to avenge his father. Thirsting for revenge, his sister Electra secretly brings him into his father's castle. No one recognizes him except his old nursemaid, who calls Aigisthos to come to greet the stranger. Orestes has no difficulty in killing the unarmed Aigisthos. Then he decapitates his mother who has by now recognized him and on her knees begs for her life.

The fate of the Atrides is fulfilled, Orestes has avenged the murder of his father. However the Great Goddess is still alive: A matricide demands to be expiated. The Erinyes-Furies, the terrifying executioners of the Goddess, pursue the mother-guilty Orestes until he collapses in a deathlike coma. His life seems at an end.

Aischilos, however, knows a remarkable sequel to this terrible story of fate and guilt, and for good reason. Apollo appears, makes the Erinyes fall asleep, because not even he can kill them with his arrows. He shakes Orestes out of his dead faint and carries him before the court of the elders of Argos. With the god's help, the elders grant Orestes a reprieve of a year in exile. In search of release from his guilt, Orestes roams from sanctuary to sanctuary, followed by the reawakened, mightily furious Erinyes. Half crazed, towards the end of the year, he reaches enlightened Athens where Apollo convinces the council of the elders to retry his case. Apollo, now supported by Athena, argues, that to avenge his father's murder was a son's duty that exceeded even the crime of matricide. With the vote of Athena, Orestes is acquitted and healed and converted to the new gods, returns to Mykenai.

In the Aischilos tragedy the Erinyes circle the theater howling: "We, the conscience of the past, cast out like dirt by these new gods. Driven into the dark underground, weh, we shall breathe fury and utter hate into man's mind. Earth, ah, ravished Earth!"

Of this end I had no knowledge; only recently did I come across this final part of Aischilos's Oresteia in one of Cornelius's old books from Berkeley.

Earth, ah, ravished Earth.

With new eyes, I see Mykenai: Two mountains, right and left, between them a deep ravine and a lower, third hill on which the castle of the Atrides stands. From the road below the two breasts and the cleft between them are so stark, that the castle is hardly recognizable - but it crowns the head of the Goddess. What sacrilege, her most sacred place occupied by people, usurped by the alien men from the far North, who dug up the sacred earth with their swords and war axes.

Gaia, raped Goddess.

For a millennium the horrified people of the Argolid watched the Goddess persue the transgressors and witnessed the terrifying tragedy in Mykenai, until Aischilos's Apollo released Orestes and enlightened him:

The Goddess is dead!

Long live the King!

But we should not let ourselves be fooled, the original sin of modern man, the rape of Gaia has not been atoned for. The mythos of Mykenai is as horrorful, as it was two millennia ago. The Erinyes still breathe hate and madness into our split mind.

Armin on the Road to Arcadia 18.9.91

ARMIN

Half a day I had spent in Athens calling all kinds of places to find the cheapest rental car. Finally I had found what I had been looking for at Pappas Rental Car, at half the going price. I had ordered the car, and next morning we had gone to pick it up. It was just around the corner from our hotel.

To our amazement we found that the little car was pulled by a centaur. I rubbed my eyes, but the centaur was still there. A handsome, strong centaur, with a broad chest and a good-natured face. Well, we told ourselves, why not travel to Arcadia with a centaur as companion and draught-animal? Nobody has done that in recent times.

Barbara steered the car and the big manbeast was happy to be reigned by such a gentle and considerate woman. He was easily satisfied and only needed a soft-boiled egg and two slices of bread with butter and honey for breakfast to be happy. Occasionally, he also liked to feed on the over-ripe figs that grew by the wayside.

We called him Armin in memory of the yak that carried Heinrich Harrer through Tibet and also because, with his shaggy hair and archaic nature, he did look startlingly like those equally ancient animals. He accepted his foreign name with equanimity. Above is a drawing of him on the road from Karytena to Andritsena in the Arcadian mountains. I also tried to take several photos of him and the car, but curiously, Armin can not be seen on any of these pictures. Always, there appears only a shabby, small Honda.

It was Armin who took us to Ypsous and into its charmed inn. We found a room under the roof with a huge fireplace and slept under heavy local sheep blankets. Ypsous is a flourishing village in the Arcadian mountains surrounded by half deserted ghost towns. I asked a young man, who had come from Athens with his girl friend for the weekend, why he thought Ypsous to be so special. He laughed, "how can I say it in English? Ypsous is a proud village and that is, why we love it."

For us the inn keeper became the main attraction of Ypsous. He had, in his youth, seen much of the world travelling as a steward on a boat. I never quite rid myself of the feeling that Armin and he were conspiring in some way to lead romantic tourists to this enchanted place. I had asked the inn keeper why the village had two names. The locals call it, much less beguiling, Stamnitza. "Oh," he said, "when Pausanias traveled through here," as if this had just happened last year, "he visited Gortys and the Gorge of the Lousios below, but he did not dare to come up here. The locals had told him that `up high,' which is `ypsous' in Greek, there roamed man-eating wolves and mountain lions. And that is how the name Ypsous got on to your maps."

I perked my ears. In all my travels in Greece, no one had ever mentioned the name of Pausanias, the famous traveler of the second century AD, who has written the first guide book to the sights of Greece. I eagerly continued to listen to him, and he told me that down in the gorge, below the monastery of Aghios Ioannis Prodromos, there was a very old nymphaion, which had been dedicated to the nymph Leda. "You know the story of Leda and the swan, don't you? Well, Leda was very attractive, and Zeus promptly fell in love with her. But she resisted his advances. So he changed into a swan, surprised her while she was bathing in the Lousios, and coupled with her. Later Leda delivered a golden egg from which hatched Artemis and Apollo. As we all know, to escape Hera's terrible jealousy, Leda was forced to deliver the twins on far away Delos."

This was fantastic, Pausanias the bard still roaming Arcadia, Leda the local nymph, and Artemis and Apollo jumping from Leto's, the Night's, Golden Egg that had actually contained Helena, what charming confusion of the old myths! But then again, there are deeper connections between Leda and Leto, both were aspects of the Goddess of the Underworld. Incredible, in this enlightened century, the ancient myths retold to beguile the unwary visitor in the best Oral Transmission.

But there was more to come. When he saw my fascination with his stories, he told me in confidence: "Only a few people know that Pausanias, when he was an old man, was exiled and spent the end of his days on a farm not far from here." He described a vague route to the place on a map... The source of this tale I have not discovered yet, could it have been Hesiod's "Days and Works"? But Hesiod had not been banned to Arcadia.

In the meantime a few young Athenians had gathered around us to listen to these stories. Faithfully, our host repeated everything once more in Greek. Finally, overcome by doubt, one of the girls asked him, where from was all his knowledge came, they had never heard of one Pausanias nor of Leda and the Swan. "Oh," he said full of honest admiration, "the German tourists taught me all this, they know so much more about our ancient history than we do."

Next morning we made our way down into the Lousios Gorge. Part of the way we drove down a terrifying road to just above the monastery, from where you had to hike on a donkey path. The monastery of Aghios Ioannis Prodromos, the "First on the Way", my favorite Orthodox saint, clings precariously to an almost vertical rock face. Karl G#tz, an old friend from Tチbingen, had accidentally stumbled unto the place in 1954 and had described it as "fairy-like." Since then, I had longed to see it one day. The monks were not particularly enthused about our visit, they had other worries. But they let us rest for an hour on their flying balcony and admire the wild setting.

Then we scrambled down the old monopati to the rushing river, for a real river it is in this dry country, most certainly worth of its own nymph. The nymphaion was there as promised. Leda or not, it has certainly been in use for thousands of years: a moss-covered cave with a karst spring from which the water gushes with great force. All around it there are holes in the rock that must have once held votive statues of the nymph.

Then Barbara decided to take a bath. Stark naked she waded into the rushing water, shouting of it coldness. And I sat in the dark hole of the nymphaion, jealously watching for the swan that surely would come swooping down on her at any moment.

Much later, at home, I read my Pausanias. Too bad, he does not write a word about a nymphaion, or about Leda and the Swan in the Lousios Gorge, nor has he heard anything of Ypsous, and most certainly he has never been banned to a farm in Arcadia. But Pausanias assures his readers that the Lousios was the coldest river in the world, at least in countries where it does not snow, and there he may yet be right.

But does "truth" really matter here? Pausanias says: "When I started to write, I always thought that the old Greek tales were often really silly. Now, that I have been to Arkadia, I have understood that the old myths have to be considered in the way the great Greek wise men did, to them these stories contained riddles rather than foolishness."

On that evening the moon was full. During the past few days I had bothered Armin with the question of whether he knew of female centaurs. Obviously, he was embarrassed by my question and mumbled crossly, "Nobody has ever seen a female centaur. For Hera's sake, we get so old, we do not need any children." But this answer had not satisfied me, and I asked the same question of our sagacious host.

"I have never seen one," said he, " but the locals claim that they sometimes appear during full moon when a Pan plays his flute especially sweetly. Go to the Heroon on the hill tonight, and maybe, if you are lucky... But be careful, don't talk to them, centaurs are exceedingly jealous." A hero'on is the old Greek name for a temple to the heroes.

So, when the sun set we went in search of the heroon - of course, without Armin. The "heroon" turned out to be an ordinary war memorial to all the fallen sons of the village since the War of Independence. But when we scared up a pair of lovers there, we knew that we had come to the right place.

Arcadia, The Centaur Maiden 18.9.91

It took a while until the moon rose behind the mountains, but even before it appeared we could already hear a Pan blow his flute. Arcadia is the home of Pan, and to this day its mountains are full of his descendants. This Pan played especially well. When finally the moon cast the valley below us into its magical light, he blew still higher, louder and more seductively, and all of a sudden, there we saw this lovely centaur maiden only a few hundred feet away from us. A rather lecherous Pan, looking at us for approval, held a mirror in his hands to direct the moon's rays at the shy girl. As vain as any other young girl, she looked at herself in the mirror and rearranged the necklace she wore. She looked so innocent and lovely.

Of course, we never told Armin of this encounter, and thus, we may be the only people - besides Picasso - who ever saw a centaur maiden.

Bassai, The Temple of Apollo Epikouros 19.9.53

To Vincent

Scully,

who taught me to see this land with new eyes.

Bassai is one of the most beautiful of the "Jewel Boxes of the Gods," as Vincent Scully calls the Greek temples so aptly. Surrounded by wild, stone-strewn mountains it lies five hours on foot from the nearest village. In its loneliness the temple of Apollo Epikouros, built from local gray limestone, grows out of a mountain side entirely at one with this landscape.

In 1953 it took Gerhard and me an entire day to walk there through oak woods and across rocky mountain, following all the time a hand sketch of the path that a student of architecture from Bielefeld had drawn for us. Bassai became the greatest experience of that long-ago summer, so full of beauty.

We slept in the southern antis of the temple, because it had been warmed by the sun during the day, and in the mountains the nights were cold in that late September. All day long we saw nobody, except for a shepherd girl, who suddenly in the morning appeared from nowhere with a bowl of goat milk for us, and who disappeared again as tracelessly as she had come.

The temple is unusually well preserved and full of puzzles. Pausanias tells us that the temple was built by Ichtinos around 420 BC. One has to know that Ichtinos was the most famous architect of classical Greece, who had built the Parthenon in Athens and the Hall of Mysteries at the sanctuary of Eleusis. At once one asks in surprise, why should such a great architect have taken on a commission for a building in this, according to Pausanias, most barbarous part of Greece? And why should anyone have wanted to build a temple on this rugged mountain ledge, hours from any inhabited place?

Already in the second century AD, when Pausanias visited the site, the temple was neglected and its four meter-high, precious wood and ivory image of Apollo had been stolen and moved to the market of the newly rich city of Megalopolis. Pausanias offers an explanation for this temple that one finds repeated in all text books: The good people of Phigalia, a marketplace six hours further down, had had it built to commemorate their rescue from a plague, and dedicated it to Apollo Epikouros, Apollo the Saviour. However, historical investigations have shown that the plague of 420 BC never reached Phigalia, and that the only epidemic that could have devastated the area occured much later. Since then the archaeologists have been arguing the date of the building, and some even dismiss the whole story including the authorship of Ichtinos.

To say it right away, I believe, Pausanias invented the story of the plague to explain Apollo's epithet Epikouros. Ichtinos, however, appears to me to be the only architect who could have designed such an ideosyn~cratic building. And people do not forget a name as famous as that of Ichtinos as easily as the date of a plague six hundred years before Pausanias' time.

Among the visible inconsistencies is the fact that the building is oriented not toward the West, as is the normal convention, but towards the South. Equally unusual and obviously related to this orientation, is a door in the eastern wall of the cella, which, say the archaeologists, had the purpose of allowing the morning sun to fall on to the image of the god. But then one discovers the pediment of the image, not in the center of the cella, its usual place, but off center, near the wall opposite to the door. It appears that the god had been made to look East over the mountains of Arcadia, somehow as the resolution of the entire "wrong" orientation of the building. Certainly a puzzling, seemingly arbitrary design for a great architect.

The unusual position of the image has a simpler explanation. We know from the sketches of a 19th-century visitor to the site, that a five meter high column stood at the end and in the center of the cella, precisely, where the great images were normally placed, and this column was crowned by a Corinthian capital, the earliest such capital in Greek art history. This column appears to have had no supporting function in the building.

Thus it appears that the venerated old replica of the god had to make way for an otherwise architecturally useless column. The first puzzle has been replaced by a second, even more enigmatic one, - or, strange thought, could this column have been the venerated object?

Bassai, View East from Mount Kotilon 22.9.91

Behind the temple of Apollo rises, moderately high, Mount Kotilon, which can be climbed in fifteen minutes. From its top one has a far reaching view of the mountains of Arcadia. In the East the view is bounded by Mount Lykaios, where Zeus had an altar as Zeus Lykaios, "Zeus of the Wolves" - of which, according to Pausanias, there were many in the area. To the West one overlooks the mountains of the Mynthias and senses the plain where Phygalia is located, and on a clear evening, the Kyparissian Sea glistens in the setting sun. The South, across several mountain ranges, is controlled by the threatening block of Mt. Ithome that dominates the almost one hundred kilometer distant plain of Messenia. The horizon behind Ithome, one discovers on a clear day, forms the Messenian Sea. Thus one can see the "two seas" from the center of the only land in Greece that had no access to the ocean.

A further reading of Pausanias, reveals the existance of another, older sanctuary on Mt. Kotilon, dedicated to Aphrodite and Artemis. After a little search we found the site. There, only indications of the foundations of the small temple and perhaps the altar plate have survived.

Bassai, Ruins of the Aphrodite-Artemis Temple 19.9.91 with Mount Ithome to the South.

A natural megaron cradles the temple, and it too, opens towards the South. If one now takes another careful look at the orientation of the Apollo temple, one discovers that the axis of both temples meet precisely on Mt. Ithome! Mt. Ithome, however, carried several very archaic sanctuaries, where until classical times human sacrifices were offered to Zeus and Artemis - naturally young men. The same seems to have been the practice at the altar of Zeus Lykaios. There is even archaeological evidence for this. Pausanias reports with horror that to his time at many places in these wild mountains sacrifices were offered, about which he would prefer not to speak. "It gives me no pleasure," he writes, "to inquire after these old rites. Maybe, they have to remain the way they have always been since time immemorial."

However, the human sacrifices practiced on Mt. Ithome and Lykaios prove, that, there, Zeus and Artemis were only the patriarchal caretakers of sanctuaries that had once belonged to the Great Goddess in one of her terrible incarnations.

It now becomes apparent that the location of the temple of Apollo in this lonely wilderness had a deeper reason: The place was a sacred site long before the temple's construction, and it lay at the intersection of several "force lines" that connected it with a number of other old power spots. In their "wrong" direction, both the sanctuary of Artemis-Aphrodite and the Apollo temple follow the forces that gave them their power, the earth-bound signs of the Great Goddess.

And now, we recognize the column in the temple. It is, of course, the Column of the Goddess, the symbol of her Sacred Tree that one finds above the Lion Gate in Mycene and on innumerable Minoan seal rings.

Thus the main "image" in the temple of Bassai was an abstract symbol of the Goddess, and Apollo was relegated to stand apart, to watch from the side lines.

Pausanias has more to say that helps to clear this mystery. He writes that his reason for visiting this remote part of Greece had been his intention to search for the dark Arcadian cult of "Demeter Erinyes." Eventually he found the last remnants of the cult in a cave in the mountains between Phygalia and Bassai. The cave has not been identified, but Pausanias gives a description of the Arcadian myth underlying the cult.

During the time of her desperate and confused wanderings in search of her abducted daughter Kore, alias Persephone, Demeter was raped in an Arkadian meadow by Poseidon in the shape of a stallion. From this forced coupling sprang a daughter Despina and a mysterious stallion named Asterion. Because of this rape and her great confusion, Demeter temporarily lost her mind and turned into a raving Erinye.

Thus in Arcadia a cult of a terrifying version of the Goddess's triad was celebrated: Despina, the Mistress, as maid, Demeter Erinyes as mother, and a third aspect "about whom," according to Pausanias, "one could not speak." Possibly it was a horse-headed Hekate as old woman. But there are also indications that Despina had a horse head. This terrible, revengeful trio, demanding atonement from the men who had violated them, haunted the mountains of Arcadia: In Arcadia the Goddess devoured men.

Pausanias also mentions a cult of Despina Epikouraia, a "helpful mistress" in temples in Megalopolis and Lykosoura, where during his time "the Mysteries were celebrated according to the Attic Rites," by priests imported from Eleusis. Today we know that these were rather late sites. Was Bassai the first attempt to reform the terrible powers of this ancient Arcadian Triad with the help of Apollo?

I argue that this was the case, and that such a reading of the architecture and the myth is the simplest explanation of Apollo's epithet Epikouros and the location of the temple far from town.

The nature of the Arcadian Goddess was so terrible, her power so pervasive that Apollo could only stand aside in Bassai, looking East through the side door seeking the assistance of Zeus Lykaios. The dread of and reverence for this Goddess lay so deep, that nobody was willing to face the consequences of removing her presence completely from the sanctuary. Thus, in a sanctuary that may have originally been dedicated to Despina, the good people of Phigalia called on Apollo for help to appease these ur-forces of Arcadia with his clarity, to break the female magic and to rescue man from the sensual arbitrariness of the virgin Goddess.

If one now looks at the architecture of the temple with this knowledge in mind, one gains a renewed respect for the genius of Ichtinos who dared to face these dangerous forces and cast their complex symbolism into a rational architectural form. The clarity of his temple design reflects that of Apollo.

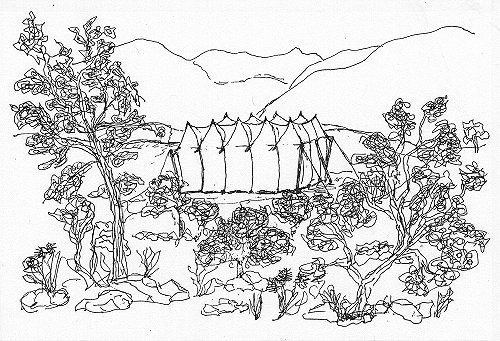

Bassai, The Tent Covering the Temple of Apollo 19.9.91

THE GREAT WRAPPING,

or

CHRISTO IN ARCADIA.

Today one can drive one's car to Bassai. All the way on the long serpentine drive, I tried to guess behind which corner the temple would first appear. But the road engineers have been unusually discrete, the parking lot is out of sight, and the temple remains hidden to the very end.

All the greater was our surprise, when a gigantic tent appeared looming over the last ridge: Ten steep, gothic spires held by masts and cables, an olympic sail ship run aground in the Arcadian mountains. For a second I thought it was the latest outrage of an ultramodern Hilton, but no, hidden under the white canvas lies the temple.

After the first shock we began to appreciate the surreal beauty of this construction. Christo would have been proud to have invented the wrapping. I cannot imagine a more fitting architectural sculpture for this sacred place of the Goddess, or a more beautiful invocation of her best aspects. With its sails humming in the wind, the huge Thing, defying gravity, floats south across the rocks. The broken noon light under its wings lets the gray stone of the temple appear new and different from past memories.

An earthquake four years ago had brought the building to the brink of collapse. The columns have shifted, the lintels are crooked and out of line, and at the moment the temple is held together by a corset of iron pipes from a gigantic erector set. A group of European sponsors is now in the process of taking the building apart completely, stone by stone, drum for drum, a thirteenth labor of Herakles. All around, between the bushes lie the pieces carefully numbered and stacked in long rows.

We spend a whole day there. Barbara hides somewhere and writes poetry. I wander through the noon light, eat the small, golden fruits of a wild plum tree - were the apples of the Hesperides as bitter as these? Finally I find sleep in the shade of an oak tree.

Now that the goat herds, these scourges of the Mediterranean landscape, have all but vanished, the land begins to recover from centuries of exploitation. The mythical Arcadian oak groves are increasing again, and Gea, what irony of our progress, appears new and lovely dressed like a young bride - even in late September

Bassai, The Death of Orpheus 19.9.91

THE DEATH OF THE BROTHER

Once, I had a brother, his name was Orpheus. When he was a child, I hated him, because he was musically so much more gifted than I. He was always praised by everybody, because he could hold a tune, and then he was given a violin.

But he was often unhappy, because he could not understand himself. Instead of writing poems, he one day gave away his violin, destroyed his music, and studied physics to follow his older brother.

We then lived together for many years. In these years I learned to love him, which was often embarrassing to him. Perhaps he felt pitied by me, he could never see his limitations or the strengths of his gifts.

I persuaded him into traveling together, to southern Germany, to Italy, and finally to Greece, in the hope that there he would find himself. But he could not see the things that meant so much to me and gave me strength. Often he was pursued by the Erinyes, and then he blindly ran straight ahead through the country side until he collapsed.

In Bassai he found peace and, sitting on a fallen lintel, spent hours painting the mountains towards the South, the row of teeth that marked the Taigetos and the block of Mount Ithome with the sea behind it. It was the only time that he took his watercolors from his backpack. I cannot find his painting any longer.

He was very shy with girls and only noticed, when they became offensive, that he attracted certain men, in Greece, in France. His first love was Barbara at a time when our first child was a year old.

Eventually the Erinyes hounded him to death. In great pain, in his last days, he told me that he had finally understood the meaning of his life and the message of Bassai.

I believe that one never loses people who one has loved, not even through death. Often I talk to this brother, telling him of the things I see, as if we were still walking together. Did he hear me in Bassai?

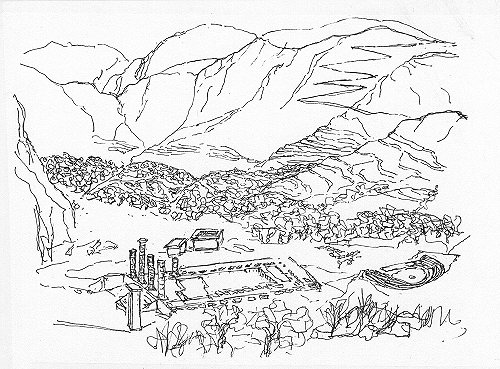

Delphi, Ruins of the Apollo Sanctuary 24.9.91

Delphi, Mykenai, and the Acropolis have turned into a kind of Greek Disneyland. Never ending streams of tourists throng the ruins, tired, bored, and uncomprehending. And the entry prices to these famous places have escalated into ransoms, eight dollars and if one wants to visit the museum, once more the same. If the authorities would only use the money for improvements, but the Archaeological Museum in Athens has turned into one of the saddest museums in the world.

One has to visit the sites late in the afternoon, when the dead-tired tourists seek peace and forgetfulness in the bars of their hotels. Then the sunlight is softer, and one has the place almost to oneself.

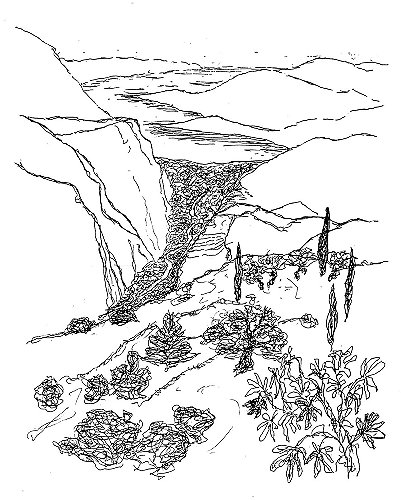

Delphi, The Pleistos Valley, Itea and the Sea 24.9.91

With this in mind, I had kept the morning ticket to the precinct of Delphi, but when at five o'clock I stood before the entrance, I could not find it anywhere. I searched all my pockets, the stub was lost. To buy a new one seemed extravagant. A sign of the Gods? Thus we scrambled up the steep hill outside the fence of the sanctuary like goats - and discovered the most beautiful spot in Delphi, high in the mountain, hundreds of feet above the stadion, with a view reaching from Itea by the sea to Arakhova at the pass to the East.

Delphi has the most dramatic location of all Greek sites. A steep valley climbs from the sea and the bay of Itea through a wild mountain scenery to finally broaden into a huge megaron. The floor of the valley is covered by a two-thousand-years old olive grove that like an immense, scaled dragon claws its way uphill. The wind passes in silvery waves through the gray leaves of the gnarled trees. The old pilgrim path followed the dry bed of the river Pleistos that meanders downhill through the grove to the sea.

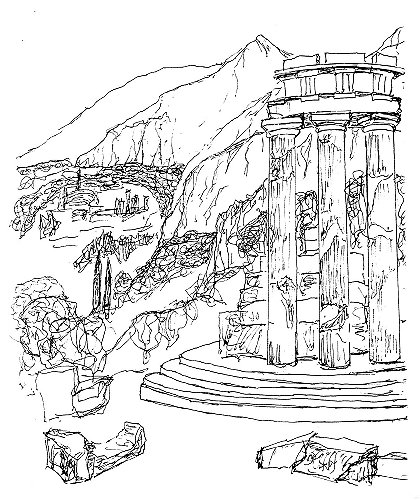

The sanctuary of the Pythian Apollo does not lie in the bowl of the megaron, as one would have expected, but is hidden from the eyes of the approaching pilgrim behind a mountain ridge, on the left shoulder of the valley. Now that the gleaming white temples have been reduced to a field of rubble, the ruins appear quite unimpressive. The once famous sanctuary of Apollo has been completely overwhelmed by the surrounding landscape. All the garish additions by the "new" gods, described by Pausanias, have vanished, and Delphi has returned to Gaia, whose sanctuary it once was.

Only when one searches the mountain slopes carefully, does one find the signs in the landscape that bestowed their numinosity to this place: Two rugged cliffs fall vertically into the valley, between them a deep, dark ravine with a strong spring of clear, cold water at its lower opening.

Because of the importance and age of the site, these sinister formations are laced with numerous old tales. Men, pursued by guilt, have jumped to their death from the Phaidriades, and from the Kastalian spring expiatory cures were expected by the faithful.

But apparently the Pythian Sibyl did not reside in this gorge, at least not since the time that Apollo slew the sacred snake of the Goddess. He must have dragged the oracle from of its old location into the daylight very early, already Pausanias knows nothing of an older place of veneration in the gorge. The spring had its nymph, Kastalia, however, the suspiciously young ancestry given her by the Greek myths, betrays her to be a late invention

However, the chthonic powers of the Goddess, her dark manifestations, Apollo could not touch, they lay below the conscious order of the new gods. He could not even usurp the power of the oracle entirely, despite all attempts at reform it remained to its end the unmistakable voice of the Goddess of the Earth. Henceforth it haunted the world, according to Pausanias, from an underground chamber beneath Apollo's new temple. The archaeologists have never found its location. They believe that the chamber and the cleft, over which the later Sibyl sat when in trance, have been buried by a mud slide or an earthquake. Only the rock below the temple from which the oldest Apollonian Pythia is said to have "sung her hexameters" is still being shown today.

Delphi, The Tholos, the Phaidriades, and the Sanctuary 24.9.91

By slaying the sacred snake, Apollo may have rescued mankind from the Pythian powers of the Great Goddess, but she revenged herself by bestowing an archetypal "reverse" on him, a chthonic aspect, which would forever cast a dark shadow over his originally youthful, clear beauty: Henceforth, Apollo became the protector of the most sought after, most feared, irrational, and sinister oracle of the Old World.

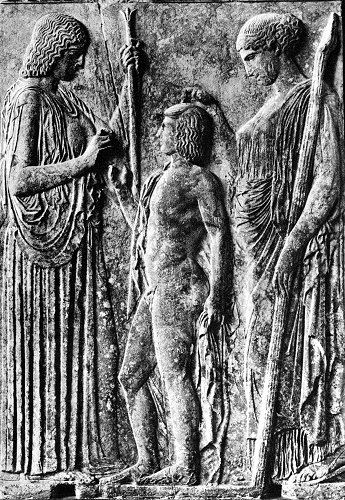

The Great Stele from Eleusis 21.9.91

THE GREAT STELE FROM ELEUSIS

Of all the objects in the Archaeological Museum in Athens I love the great votive stele from Eleusis best. It shows the Goddesses, Demeter to the left and Kore-Persephone to the right of the young Triptolemos, into whose hand Demeter is laying a grain of corn. Above his head Persephone holds the pomegranate. In her left Demeter carries a "column", her Sacred Tree and Kore the Torch of Light. The stele radiates a serenity that few other images from the classical period own.

The story behind the scene is the following. When Demeter was still young, gay, and innocent, she bore Zeus a daughter Kore and a son Iakkhos. She loved Kore beyond measure, and was inconsolable, when, one day, Kore disappeared without a trace. Kore had gone to gather red poppies in an Arcadian meadow, and nobody had seen her since. Desperate, Demeter asked everywhere for her daughter. The only one who had been near, was a swine herd, who had tended his animals in an oak grove not far from the meadow. He told Demeter how suddenly a great crack had opened in the earth, and how a carriage drawn by black horses had vanished in it a with great noise. He had heard cries of "Help! A Rape!" from inside the carriage. His pigs had run after the carriage, and they too had disappeared under~ground.

For weeks Demeter wandered across the land, refused to eat or drink, and dayly became more depressed. One evening she knocked at the door of Kelaios, the king of Eleusis, asking for shelter for the night. Because she had disguised herself, the good king did not recognize her, and offered her to stay and to become a wet nurse to his youngest son Daimophoon. Demeter accepted and during the following night, grateful of the king's hospitality, decided to bestow immortatility on Daimophoon. She used a puzzling magic, she roasted the infant over the open fire in the hearth, as one roasts grain. An older son of the king surprised her during this work. Demeter shot him an angry look, which changed him into a lizzard on the spot. The spell was broken, and Daimophoon died in the fire. In an attempt to console the despaired Kelaios, Demeter promised to introduce his remaining son into her Mysteries and to teach him the secrets of the grain. This child was Triptolemos. Thus Triptolemos became the first hierophant of the Goddess's Mysteries.

The Eleusian Mysteries became famous and survived until late Roman times. What was their secret? A fertility magic or the tenets of agriculture could hardly have held kings, emperors, poets, philosophers, and simple men in their spell for over a thousand years.

Before I try to unravel the mysteries of Eleusis, I have to finish the story of Demeter and Kore. After the mishaps in King Kelaios's house and not without great reluctance, Demeter finally asked Helios, the Sun God, for the whereabouts of her daughter. Helios, who saw everything, knew what had happened. Hades, the King of the Underworld, had fallen in love with Kore, and had obtained the half-hearted permission of her father Zeus to marry her. Hades had surprised Kore sleeping in the meadow among the red poppies, had raped her right then and there - what virgin ever lost her maidenhead in a conjugal bed in those days? - and had abducted her into the underworld in his carriage. There Kore made a deadly error. Hungry as she was after all the excitement, she ate the seven love seeds of a pomegranate offered her by the sly Hades, who knew only too well, that one who made love and ate of the pomegranate, could be claimed by the underworld.

After this discovery, Demeter, half deranged and blind, erred through the lands, and swore that she was going to halt all growth on earth until Zeus would bring her daughter back from the dead. Zeus did have a bad conscience, and when the people on earth began to die of hunger, he arranged for a compromise between Hades and Demeter. In the future, Kore would spend nine months with her mother on earth and three underground as Persephone, the Queen of the Dead.

We know that a symbolic re-enactment of this myth was at the core of the mystical rites in Eleusis. In the older mysteries women undoubtedly celebrated the transmission of female knowledge of birth and death from mother to daughter. Originally, the Mysteries of the Great Goddess were a female initiation cult, from which men were excluded. In the remote parts of the country this did not change until late Hellenistic times. To the Mysteries of the Three Goddesses in Arcadia men had no access. However, since Triptolemos's initiation into the Attic Mysteries men were admitted to the Eleusian celebrations. Demeter and Kore had taught Triptolemos much more than the ancient knowledge of the lunar cycles of female nature.

Our knowledge of the rites in Eleusis are very limited. Not only were the participants in the Mysteries forbidden to talk of their experiences, the greatest insights could simple "not be said", they were averbal. In the ritual the Last Things were shown without words, in symbols, just as the Christian priest "demonstrates" the Host before the faithful.

The great symbol, which the hierophant held up for all to see, was an ear of corn, the sign of maturity, Demeter's attribute. At the same time the grain was also a symbol of Kore. Because as the seed of grain dies in the earth, it germinates and initiates a new cycle of growth, ripening, and dying, just as Kore returns from the underworld in the spring, grows, makes love, dies, and diappears again in the earth.

There are indications that the transformations of Kore from virgin, through her rape, to her death and return were also enacted in Eleusis. But it is hard to imagine that this should have been a sacred theater, in which the hierophant reenacted the rape with a priestess, as some investigations of the Mysteries want us to believe. It was much more likely a showing of abstract symbols.

We know more about the climax of the rites. It took place at midnight. The mystagoges stood tightly packed in the great hall of the sanctuary. Each carried a candle, as yet unlit. The hall was in complete darkness. All knew Kore to be in the underworld. At this breathless moment, pregnant with anticipation, the hierophant appeared, holding up the ear of corn, and calling Kore by her ritual name Brimo, he shouted: "It is a boy! Brimo has born Brimos! Brimo anesti!" And from the depth of the altar appeared the Light that was now handed from pilgrim to pilgrim. Everyone lit his candle from it, until finally the room was filled with light. A wild euphoria overcame all and with shouts of "Brimo anesti" the people fell into each others arms and kissed each other with great joy without regard of their station in life: women and men, poor and rich, friends and strangers, kings and beggars.

She has

born a son!

Brimo anesti! Brimo is risen!

And all saw the miracles of the Ear of Corn and the Light.

Where I know these details from? The words of the hierophant, the ear of corn, the darkness at midnight, the emergence of the light, and the excitement of the pilgrims are all well known from a Homeric poem and from classical drama. But an almost identical ritual is still performed to this day: At the same time of the year, determined by the same lunar calendar, Orthodox Christianity celebrates Easter; the same pregnant darkness at midnight, the candles, the sudden light that wanders from hand to hand are all there. Only, the priest shouts "Christo anesti!" and all hug and kiss each other in great joy. It would not surprise me, if the Greek Easter colors, the red of death and the underworld and the white of light, existed already at Eleusis. And both rituals have the same meaning: The Promise of the Resurrection of Man.

But here end the parallels. From here the Christian and the Eleusian path run tangentially apart. In the Greek myth the ear of corn showed the cyclical nature of all life on earth, including that of man. In the Christian myth the God leaves earth in a straight, tangential line. The Christian myth promises man's resurrection through Christ at the end of our time. In the Greek myth Kore testified, that "resurrection" can be found in the age-old mystery of woman, here and now. And through love, Woman does not only reproduce herself, but, the greatest of all obvious miracles, bears her opposite, a Son, Brimos!

As a Man, uninitiated in the mysteries of woman, Christ knows nothing of these eternally female mysteries. He knows nothing of the sacrament of birth. He never loved a woman, how can he know that physical love and death are one? Before he suffered his own, he knew nothing of death. He teaches the way of the negation of death through suffering and the centrifugal flight from the wheel of life on earth. The way of sufferance was also the one by which Gerhard gained his insight. The deep, joyful knowledge of woman about birth was buried forever by the Church's adoption of the Augustinian Dogma of Original Sin. Finally the murder of the Goddess had been fulfilled.

This is not intended as polemics against Christian dogma. The parallels between Orthodox Easter and Eleusis, which, curiously, none of Jung's students studying the Eleusian Mysteries has seen, is merely intended here to illuminate the happenings at Eleusis.

The adoption of Triptolemos by Demeter can now be seen as the mythological expression of the modifications the Greeks made to the initiation rites of matriarchy, with the intention of making them accessible and meaningful to men and women alike without destroying the fundamental substance of female insight. The symbolic reference to the cyclic character of the grain elevated the myth above the lunar, gender-bound cycles of woman that reigned matriarchy. The yearly rhythm of sowing, growing, and decay depends on the cycles of the male sun not that of the female moon. The same is meant by the appearance of the light at the Mysteries, it was a super-mundane demonstration of the fertilization of the creative darkness of woman by the male principle.

However, the final, decisive act of the drama was the miracle of the birth of Brimos. This demonstration of the unity of male and female by woman points to her role in the understanding of life and death. The miracle of Brimos completes the archetype of Demeter and Kore that shows the oneness of life and death and thus solves the ultimate question of the meaning of life.

Many years ago, long before I knew more of Eleusis than its name, I had a conversation with a young woman at an otherwise forgotten house party somewhere in Hollywood. I had just returned from a visit to Mount Athos - the sacred mountain of Orthodox Christianity in Northern Greece - and had described to her, how the monks there, exercised themselves in learning to conquer death without female help. "You know," said this woman, "I often feel really sorry for men. They know nothing. All their lives long they attempt to devise philosophies and religions, which they hope would take away their fear of dying." She smiled, however, she became serious again at once. "While listening to you, I just understood for the first time, why I have born four children in very close succession. At each birth I went through such a great euphoria, that I longed to repeat the experience. Every time, quite without pain, smiling to myself, I floated outside and above my body and watched the birth of the child take place. I just realized that this was an experience of death. It is given to woman to experience the unity of birth and death directly." Later she added: "I have thought about this. I believe, that this experience could also be accessible to a man who truely loves a woman. I assure you, like making love, death is a sensual experience full of surprises."

The ecstatic reports of men who took part in the Mysteries indicate, that the images shown in Eleusis may have conveyed a similar insight. Sophokles says: "Thrice happy is the man who has reached the goal (telos) in Eleusis. He alone will find life in death."

The tradition that gave power to the rites of the Mysteries is dead. The details of the sacred drama of Eleusis have been almost completely obscured. The ability, however, to reach the same insights still lies deep within ourselves, equally, in man and woman.

And if one day our subconscious reveals to us our death, when it presents us with the euphoric experience of wandering through its land with a clear mind, and we suddenly see the beauty of life in dying, then a knowledge of Eleusis may help to dispell all doubts and fears.

The Gestalt of a man's death is surely female. Happy is the man wo knows the woman, who will guide him through his Arcadia.