The Stones of Greece

Delphi

Google-Map

The

Sanctuary****

1500 BC- 393 AD

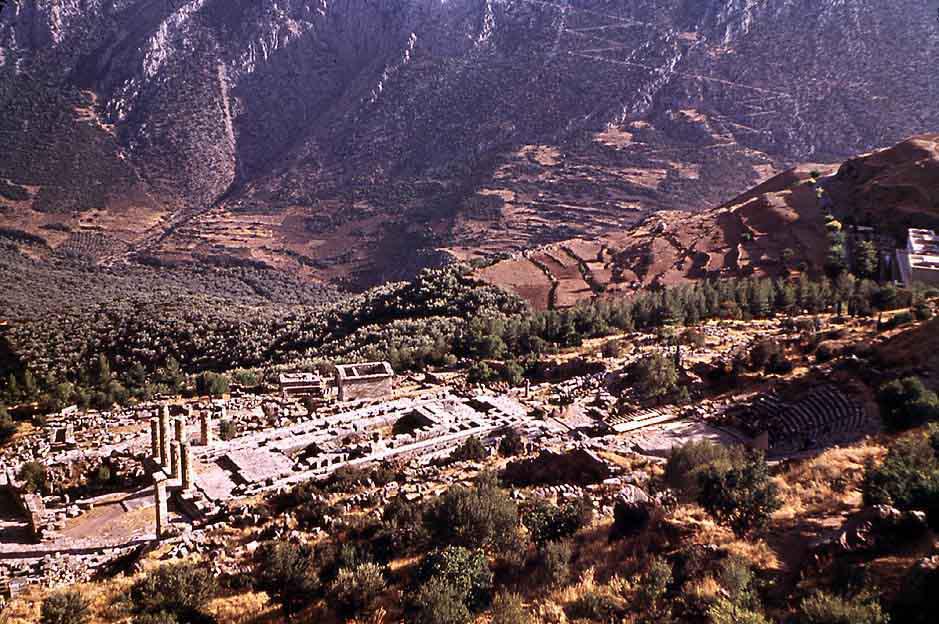

The Sanctuary from up high RWFG 1954

The Apollo Temple and the

theater. The Delphi Museum is visible on the far right.

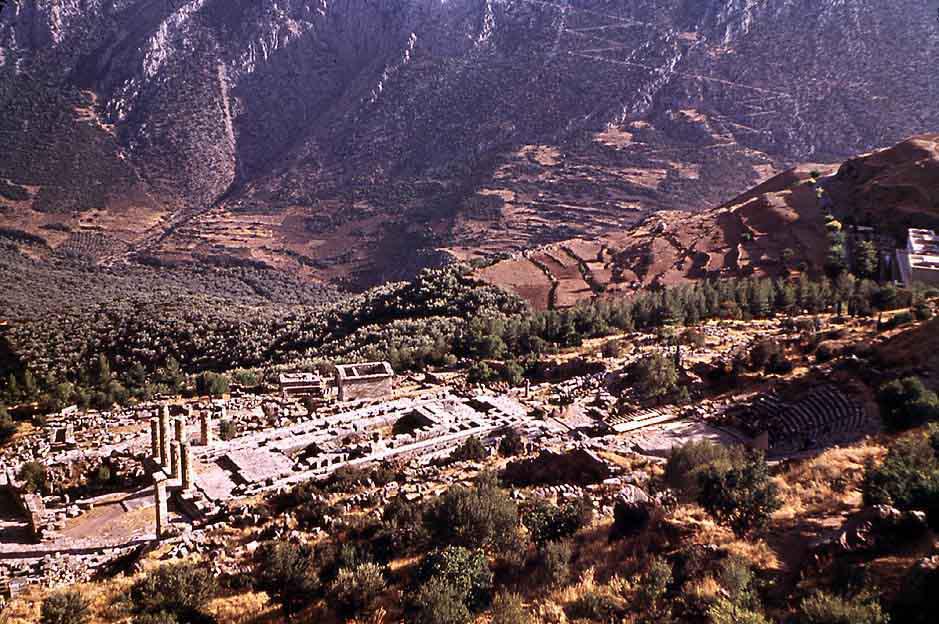

Located amidst breathtaking scenery in central Greece, the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi was the most important sacred site in the Greek world. Revered as early as 1500 BC, the sacred precinct was home to the Pythian Oracle, an entanced priestess through whose mouth the god counseled his people.

The Sanctuary as seen from the old path to Itea and the sea,

where

the pilgrims arrived and which Pausanias describes, RWFG 1991

Excavations reveal that Delphi was first inhabited in early Mycenaean times (15th century BC) and that priests from Crete brought the cult of Apollo to central Greece in the 8th century BC. The version of Apollo worshipped on Crete was Apollo Delphinious - the god in the form of a dolphin - and it was from this that the holy city derived its name.

As the center of the world and the dwelling place of Apollo, Delphi was thronged with pilgrims from across the ancient world. Generals, kings, and individuals of all ranks came to the Oracle of Delphi to ask Apollo's advice on the best course to take in war, politics, love and family. After the inquirer made a sacrifice, a priestess uttered a cryptic pronouncement in a trance which was then translated by a priest.

The 6th century BC saw the political rise of Delphi and the

reorganization of the Pythian Games, ushering in a golden age that

lasted until the arrival of the Romans in 191 BC. Numerous treasuries

were built in the Sanctuary of Apollo to house votive offerings of

grateful pilgrims. In the 4th century BC, a theater accommodating

5,000 spectators was built in the precinct. It was restored in 159 BC

by the Pergamene king Eumenes II and later by the Romans.

From

Sacred

Destinations

Maps of Delphi

Map of Delphi, Map copyright PlanetWare.com

Map of the Sacred Precinct, Map copyright PlanetWare.com

Delphi,

Apollo Temple***

4th cent BC

Apollo Temple and the Theater, RWFG 1991

The columns of the Apollo Temple, RWFG 1991

The Temple of Apollo seen today dates from the 4th century BC. There

were two earlier temples on the site: the first was burned in 548 and

the second was destroyed by an earthquake. Some archaic capitals and

wall blocks are preserved from the first temple and many wall blocks

and some pediment sculptures are extant from the second.

Wikipedia

The

Treasuries**

5th cent BC

The treasuries where the votive gifts of the supplicants were stored line the Sacred Way to the temple.

Treasury of the Athenians, 490 BC

Giagantomachie: the Goddess Thetis in Dionysos' Lion Chariot fighting

the Giants

North Frieze of the Treasury of the Siphnians 450 BC,

(in the Museum)

Photos ACSA umich.edu

Delphi, The Museum****

The feet of the Charioteer in the Museum, RWFG 1954

The first museum of Delphi was built in 1903 based on the plans of

the French architect Albert Tournaire and funded by the banker and

philanthropist Andreas Syngros. It was later modified to a larger

two-storeyed construction in 1938 based on the architectural designs

of museum architect Patroklos Karantinos. The extension in 1938 was

necessary in order to accommodate the growing collection of

antiquities found at the excavations by the École française

d'Athènes and their Greek counterparts in the later years. In 1975,

the museum was enriched with the chryselephantine objects that were

recently excavated along the ancient sacred way of the oracle

complex. In 1974, a new room was added for the exhibition of the gold

and ivory finds from the sanctuary.

From Wikipedia

For more informative and splendid illustrations: Latsis'

Museum Catalog

Delphi,

The Kastalian Spring**

~2000 BC - 493 AD

The Hellenistic basin of the Kastalian Spring, RWFG 1954

Before Apollo came along, the serpent Python was the ancient guardian of Delphi's Castalian Spring. Python was the son of the Greek goddess Gaia, Mother Earth, who was likely the original deity who was venerated at the site. Ancient legend has it that Apollo killed the Python, claiming the spring for himself. He then personally founded the oracle of Delphi, proclaiming:

”In this place I am minded to build a glorious temple to be an oracle for men, and here they will always bring perfect hecatombs, both they who dwell in Peloponnesus and the men of Europe and from all the wave-washed isles, coming to question me. And I will deliver to them all counsel that cannot fail, answering them in my rich temple.” (Hymn to Pythian Apollo, 285-295)

The Castalian Spring, in the ravine between the Phaedriades at Delphi, is where all visitors to Delphi — the contestants in the Pythian Games, and especially suppliants who came to consult the Delphic Oracle — stopped to wash their hair; and where Roman poets came to receive poetic inspiration. This is also where Apollo killed the monster, Python, and that is why it was considered to be sacred.

Two fountains, which were fed by the sacred spring, still survive. The archaic 6th century BC fountain house has a marble-lined basin surrounded by benches. There is also a Hellenistic or Roman fountain with niches hollowed in the rock to receive votive gifts. The Castalian Spring itself predates classical Delphi. The ancient guardian of the spring was the serpent Python, which was killed by Apollo in its lair beside the spring.

This spring in a ravine once provided drinking and washing water for

the priestesses who pronounced the oracles here. The spectres of

three women are said to sometimes wander the area, which is now

closed off to visitors - supposedly because of falling rocks.

However, a channel filled with water running from the spring comes

out to the pathway.

From Sacred

Destinations

The Oracle

at Delphi

2000 BC - 2000 AD

The Oracle telling King Aegeus that he will father a son – Theseus – when drunk, which, of course happened, and so drunk he was that he didn't notice that his wife also lay with Poseidon on the same night. - This started the mythical life of Theseus with the dichotomy of being god and human. (RWFG)

The oracles of Delphi were given in a small chamber in the Temple of Apollo called the adyton, which only the Pythia could enter. The Pythia (named for the Python slain by Apollo) was a priestess who spoke as a possessed medium for Apollo, the god of prophecy. Usually a middle-aged peasant woman, she was specially selected and trained for her role. She practiced sexual abstinence and fasting before giving oracles.

Questions were submitted to the Oracle on a tablet, some examples of which survive. When she was delivering oracles, the Pythia was said to be in a mild trance. The Pythia spoke for Apollo in an altered voice and often chanted her responses. The response was then written down and sealed by a priest and given to the inquirer. No copies of any answers have yet been found.

The Oracle only functioned on certain days and under specific circumstances. On one occasion recorded by Plutarch, the Delphi temple authorities forced the Pythia to prophesy on an inauspicious day to please the members of an important embassy. She went to the adyton unwillingly and was seized by a powerful and malignant spirit. In this state of possession, instead of speaking or chanting as she normally did, the Pythia groaned and shrieked, threw herself about violently and eventually rushed at the doors, where she collapsed. The frightened consultants and priests ran away, but later came back and picked her up. She died a few days later.

According to many ancient authors — including historians Pliny and Diodorus, the philosopher Plato, poets Aeschylus and Cicero, the geographer Strabo, the traveler Pausanias, and even a priest of Apollo who served at Delphi: the famous essayist and biographer Plutarch — the Pythia received her oracles from a chasm in the earth that emitted vapors "as if from a spring." Plutarch noted that the gas smelled of sweet perfume.

Strabo (64 BC-25 AD) recorded:

"They say that the seat of the

oracle is a cavern hollowed deep down in the earth, with a rather

narrow mouth, from which rises a vapor that produces divine

possession. A tripod is set above this cleft, mounting which, the

Pythia inhales the vapor and prophesies."

Modern study of the oracle began around 1900, when French excavations of the site were undertaken. When no chasm was discovered that matched the ancient reports, the English classicist Adolphe Paul Oppé declared that no chasm or gases had ever existed at Delphi. His strongly-argued report was immediately accepted. His theory was reinforced in 1950 when French archaeologist Pierre Amandry added that only a volcanic area, which Delphi was not, could have produced a gas such as the one described in the classical sources.

But in the 1980s, a geological survey discovered an active fault line

that ran along the south slope of Mount Parnassus and under the site

of the oracle. Given the prevailing opinion, no significance was

attached to the find. But faults are known to bring gases to the

earth's surface, and experts began to question the accepted doctrine.

This synopsis, written by a woman, is quoted from Sacred

Destinations