Sven Hedin's Tarantass Orenburg November 1893

Sven Hedin's Expeditions

1983 -1935

From Orenburg across the Pamirs to

Kashgar

3 Nov 1893 - 1 May

1894

Google

Map 1

To view his

route click on Google Map 1

Orenburg

14

November 1893

Sven

Hedin's Tarantass Orenburg November 1893

An unbroken railway journey of 1400 miles, the distance which separates Orenburg from St. Petersburg, is hardly an unmixed pleasure. The four days and nights which it takes to cross European Russia in this manner are, however, neither long nor dull. After leaving Moscow, there is always plenty of room in the train. You can arrange your corner of the carriage as comfortably as circumstances will allow, and let your gaze wander away over the endless fields and steppes of Russia. You may smoke your pipe in perfect peace, drink a glass of hot tea now and then, and trace the progress of your journey on a map.

At the end of four days of railway travelling I arrived, considerably shaken and jolted, at the important town of Orenburg. The town was not very interesting. In one place were sold all kinds of carts and conveyances, telegas and tarantasses. From Orenburg to Tashkend is another 1300 miles, so that I now had before me a drive nearly as long as the four days' railway journey. Thirteen hundred miles in a tarantass, in the month of November, across steppes and wastes, over roads probably as hard as paving-stones, or else a slough of mud, or impassable from snow!

I had already (1890-91) made the railway journey from Orenburg to Samarkand, and wished to take this opportunity of seeing the boundless Kirghiz steppes and the Kara-kum Desert. It is possible to travel by the post. But this means a change of conveyance at every station; and as there are ninety-six stations, the inconvenience and waste of time caused by the repeated unstrapping and re-arranging of one's luggage can be imagined. It is better to buy your own tarantass at the beginning of the journey, stow away your baggage once for all, stuff the bottom of the conveyance with hay, and make it as comfortable and soft as possible with cushions and furs—a tarantass has neither springs nor seats—and only change horses at the stations. As a rule nothing eatable is to be obtained at the stations. Upon quitting Orenburg you leave behind every trace of civilization ; you plunge into tracts of absolute desolation, and are entirely dependent upon, yourself.

I bought a perfectly new tarantass, roomy and strong, and provided

with thick iron rims round the wheels, for seventy-five roubles (£7);

I subsequently sold it in Margelan for fifty (£5). It was an easy

matter to stow myself and my luggage (about six cwt.) away in it; and

for nineteen days and nights without a break it was my only

habitation.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Irghiz

November

1893

The

way to Irghiz in Summer!

Panoramio

Irghiz, standing on an eminence overlooking the river of the same name, is a ukreplcnye (fort) and its commandant a uyasdny natyalnik, or chief administrative officer of the district. The place has a small church, and about a thousand inhabitants, including the garrison of a hundred and fifty men, of whom seventy were Orenburg Cossacks. The greater number of the inhabitants were Sart merchants, who come there periodically to barter with the Kirghiz.

Off we went again with our four-in-hand. The sun set about five o'clock ; and as it lingered for a moment, like a fiery cannon-ball, on the distant horizon, a subdued purple radiance was diffused across the steppe. At that hour the light produced very extraordinary effects. Having nothing with which to make comparisons, you are liable to fall into the strangest blunders with regard to size and distance. A couple of inoffensive crows hobnobbing together a short distance from the road appeared as large as camels, and a tuft of steppe grass, not more than a foot in height, looked as big as a vigorous tree.

Konstantinovka, Camels for

Horses

Nov 1893

In

Konstantinovka the horses were replaced with camels.

Behind Irghiz we plunged into the Kara-kum Desert ( Black Sand). Vegetation grew scantier and scantier, and in a short time we were immersed in an ocean of sand. This region was at one time covered by the waters of the Aralo-Caspian Sea, a fact evidenced by the prevalence of shells of Cardium and Mytilus, which are said to have been found far in the desert.

It was a moonlit night when I arrived at the little station of Konstantinovskaya, where the travellers' "room" was merely a Kirghiz kibitka (tent), not very inviting at that period of the year. From this place to Kamishlibash, a distance of eighty miles, Bactrian camels are generally used, as horses are not strong enough to drag the conveyances through the barkhans or sand-hills, which occur along that portion of the route.

I had only been waiting a few minutes at Konstantinovskaya when I

heard a well-known gurgling sound, and the fantastic silhouettes of

three majestic camels became visible in the moonlight. They were

harnessed all three abreast to the tarantass, and when the driver

whistled set off at a steady

trot. Their pace was swift and even, and they often broke into a

gallop.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Lake Aral

23 Nov 1893

Lake Aral lies 157 feet above the level of the sea; and its area is 27,000 square miles, nearly the size of Scotland. The shores of the lake are barren and desolate, its depth inconsiderable, and the water is so salty that it cannot be used for drinking purposes,

A thick fog bank hung over Lake Aral to the west; while in the north

and east the sky was clear. Between the stations of Alti- kuduk and

Ak-julpaz the road ran close by the side of the lake, often not more

than half-a-dozen paces from it. The fine yellow sand was so hard and

compact that the camels' hoofs left scarcely a perceptible trace; but

farther up it rose into sand-hills, and there the tarantass sank in

up to the axles.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Kazalinsk

25 November

1893

In

Kazalinsk Hedin's tarassa was drawn by 5 horses

Kazalinsk stands on the right bank of the Syrdaria, 50 miles by road

from Lake Aral. It consisted of 600 houses inhahabited by Russians

and Ural Cossacks. The rest of the population was made up of Sarts,

Bokharans, Tatars, Kirghiz, and a few Jews. The richest merchants

were natives of Bokhara; the Kirghiz, on the other hand, being poor.

Their more wealthy kinsmen live on the steppe, and derive their

riches from their herds

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Pheasants along the Syr-Darya

River

29 Nov 1893

For several days we followed the banks of the Syr-Darya (Jaxartes). Here the vegetation was very abundant. It consisted of kamish, saksaul, and prickly shrubs, which grew in thickets, forming a veritable jungle, through which the road often wound in a sort of narrow tunnel.

This was a favourite haunt of tigers, wild boar, and gazelles; and there were geese, wild-duck, and above all immense numbers of pheasants. These last were so bold, that they sat by the side of the road, and calmly contemplated the passer-by ; but the moment we stopped to fire they rose with whirring wings. Their delicate white flesh was indeed a welcome addition to my bill of fare, the more so as my provisions, so far as delicacies were concerned, had very nearly come to an end. The Kirghiz shoot the pheasants with wretched muzzle-loaders.

On November 29th the sunset was very beautiful. The heavens in the

west glowed as from the reflection of a prairie fire, and against it

the gnarled and tufted branches of the saksaul stood out in inky

blackness. The whole steppe was lit up by a magic fiery glow, while

in the east the sombre desert vegetation was bathed in gold.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Turkestan

1 Dec 1893

Turkestan

Akhmed Yasovi Mosque, 1397

Panoramio

At last we came within sight of the gardens of Turkestan, with its tall poplars, long grey, clay walls, in part new, though mostly old and ruinous, and its magnificent saints' tomb dating from the time of Tamerlane (fourteenth century). We were soon driving through the empty bazaar—it was a Friday (December 1st), the Mohammedan Sabbath—to the station-house, where a Kirghiz smith at once set to work to mend the broken axle of the tarantass.

The only object that could at all justify a delay of a few hours is

the colossal burial mosque, erected in 1397 by Tamerlane in memory of

a Kirghiz saint, Hazrett Sultan Khoja Ahmed Yasovi. Its pishtak or

arched facade is unusually high flanked by two picturesque

tower

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Chimikent

Dec

1893

Just as darkness was coming on, we reached the town of Chimkent, the first place that was familiar to me from my former journey.

There, one of the side horses of the troika became unmanageable,

kicked and reared, and would on no account let himself be harnessed.

It took six men to hold him, two on each side, one at his head and

one at his tail ; and when, at last, he was harnessed and let go, he

started off at a furious pace, so that his eyes blazed and sparks

flew from his hoofs.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

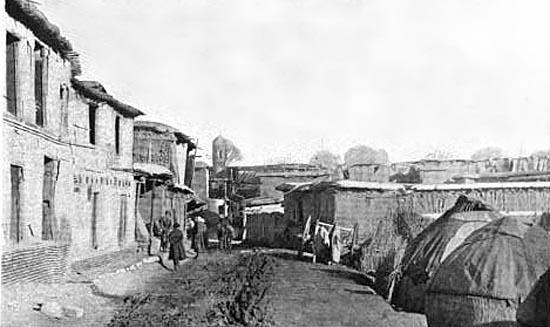

Tashkent

4 Dec 1893

The

streets of Tashkent

Two more long stages through mud a foot deep to Tashkent, and there was only a short piece of the road left. The way seemed to be endless ; although the road was now very good. I had had enough of tarantass driving ; and it was with a feeling of real pleasure that I turned into the streets of Tashkend shortly after midnight on December 4th, and secured a couple of comfortable rooms at the Ilkin Hotel.

Thus ended my nineteen days' drive; in the course of which I had covered 1300 miles. I had watched the days growing longer, although mid-winter was approaching, and had left behind a region that was swept by snowstorms, and where winter was in full career.

I spent nearly seven weeks in Tashkend. The governor-general, Baron Vrevsky, received me with boundless hospitality; I was his daily guest, and enjoyed the opportunity of making acquaintances who were of great assistance to me in my journey across the Pamirs.

During Christmas and New Year I was a guest at many festivities. Christmas Eve, the first and pleasantest during my travels in Asia, I spent at the residence of Baron Vrevsky in almost the same manner as at home in the North. Many of the Christmas presents laid out awaiting their future owners were accompanied with French verses ; and in the middle of the palace stood a gigantic Christmas tree, made of cypress branches, and decorated with a hundred tiny wax candles.

We spent the evening in the customary ways, in conversation, by a smoking samovar in the drawing-room, which was tastefully furnished with all the luxury of the East. Portraits of King Oscar, the Tsar, and the Emir of Bokhara, each signed with the autograph of the original, adorned the walls. The fair sex could not have been represented more worthily than by the Princess Khavansky, the governor-general's charming daughter, who did the honours at all entertainments, private as well as official, with grace and dignity.

Christmas Eve was kept en famillc; but for New Year's Eve Baron

Vrevsky invited some thirty guests to his house. As midnight

approached, champagne was served round, and in silence and with

uplifted glasses we awaited the striking of the clock. As the New

Year came in, the words "S' novom godom " ("A Happy

New Year to You!") were spoken to right and to left by each

person.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Chirchiq

25

Dec 1893

I had a great deal of shopping to do. I laid in a stock of tinned provisions, tea, cocoa, cheese, tobacco, etc., sufficient to last several months ; I also bought sundry small articles, such as revolvers, and the ammunition for them, clocks, compasses, musical-boxes, field-glasses, kaleidoscopes, microscopes, silver cups, ornaments, cloth, etc., all intended as presents for the Kirghiz, Chinese, and Mongols. In the interior of Asia textiles almost take the place of current coin ; for a few yards of ordinary cotton material you may buy a horse or provisions to last a whole caravan several days. Finally, on the special recommendation of the governor-general, I was enabled to purchase the latest and best ten-verst maps of the Pamirs, a chronometer (Wirdn), and a Berdan rifle, with cartridges and twenty pounds of shot.

When at length my preparations were all completed, I bade farewell to my friends in Tashkend, and started again on January 25th 1894 at three o'clock in the morning.

I had not got farther than Chirchick, where I had to pay 37 roubles

for the ninety odd miles to Khojent and for eight horses (for two

carriages were now necessary), when I was delayed for want of horses.

There was so much traffic that, although the stations keep as many as

ten troikas, they are often short of horses; and when a traveller is

unfortunate enough to clash with the post, for which the

station-masters are responsible, there is nothing for it except to

possess one's soul in patience.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Khojand

27 Dec 1893 - 2

Jan 1894

(aka Leninabad)

After several delays, caused by want of horses, I at last, on the 27th, reached Khojent, where my sole errand was to take measurements of the Syr-daria. I shall say a few words about these further on ; of the town itself I have already given a description in my former book. Suffice it, therefore, to say a word or two only about the large bridge which spans the Syr-daria. It is divided into two parallel roadways for the convenience of traffic, is provided with a black railing, and is built on piles resting on three wooden caissons filled with stones.

The owner, who is a private person, made a profitable contract with

the Government for thirty years. During the first twenty he was to be

allowed free possession of his bridge; but for the following ten he

was to pay 3000 silver roubles (£300) a year to the Government. Of

these ten years six have still to run. The cost of building the

bridge was put down at £5000; but it has had to be rebuilt twice.

When the ten years have run out,

the bridge is to be handed over to the Government in good

condition.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

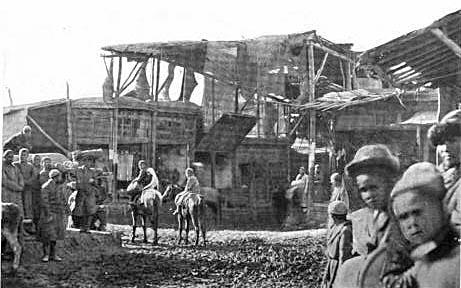

Kokand

4 -30 Jan 1894

Entrance

to a bazaar in Kokand

In Kokand there are thirty-five madrasas or Mohammedan theological colleges in the town. I mention in particular the madrasa Hak Kuli, which was founded in the year 1221 of the Hejra (1806). The madrasa Khan has eighty-six rooms and three hundred pupils. The madrasa Jami, with its large quadrangle shaded by poplars, willows, and mulberry trees, its minaret, its beautiful cloisters with van-coloured paintings on the chequered ceiling, and its carved wooden pillars, between which a number of young mollahs (theological students) were sitting reading, likewise has eighty-six rooms, but only two hundred pupils.

At the time of my visit there were five thousand students at the different madrasas in Kokand maintained by donations, while three hundred were living at their own expense. Besides the institutions which I have just mentioned, there were, connected with Mohammedan instruction, forty-eight mekteb-khaneh or schools for six hundred boys and two hundred girls, and thirty khari- khaneh or schools founded with money left for the purpose, and situated near the testators' graves. In these some three hundred and fifty pupils are educated. Finally, there were three Jewish schools, with sixty pupils. The population of Kokand was about 60,000, of whom 35,000 were Sarts, 2000 Kashgarians and Taranchis, 575 Jews, 500 Gypsies (Lulis), 400 Dungans, 100 Tatars, 100 Afghans, 12 Hindus, as usual moneylenders, and 2 Chinese. To this add 350 Russians and a garrison of 1400 men. The rest were Tajiks.

In Kokand I visited a couple of hammam (hot baths), naturally without

making use of them; for they offered the opposite of what we

understand by a bath, and were rather hot-beds for the propagation of

skin diseases. They were entered through a large hall, with

carpet-covered benches and wooden columns; this was the room for

undressing in. From that you passed through a number of narrow

labyrinthine passages to dark, steamy, vaulted rooms of different

temperatures. In the middle of each there was a platform on which the

bather is rubbed and washed by a naked shampooer. A mystic twilight

prevailed in these cellar-like crypts, and naked figures with black

or grey beards flitted about through the steam-laden atmosphere. The

Mohammedans often spend half their day in the bath, smoking, drinking

tea, and sometimes even taking dinner. The moral condition of the

town is terribly degraded; the female dancers, who perform at

weddings and other ceremonies, contribute to this in no small

degree.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Margelan

4

-22 Feb 1894

After sending my baggage direct to Margelan in a couple of arbas (carts), I left Kokand on January 3Oth in my old tarantass, and directed my course northwards to Urganchi, a largish kishlak (winter village), where the fair was in full swing and the streets full of people. The road led through an unbroken succession of villages, and on either side of it were ariks or channels, tributaries of the irrigation system which waters the oasis of Kokand.

On February 4th, via Yaz-auan, I reached Margelan, the chief town of Fergana, where the governor, General Pavalo-Shveikovsky, received me with great courtesy. During the twenty days I spent in his house, occupied in completing the last preparations for my journey across the Pamirs, he showed me the greatest kindness, and gave me much valuable advice.

During my stay with Baron Vrevsky in Tashkent we had many conversations together about the Pamirs, the outcome of which was, that I conceived the idea of crossing that region on my way to Kashgar. But no sooner did I mention my purpose than, almost with one accord, well nigh every voice was raised to dissuade me from it.

There were only two men who did not see my project in such dark colours, namely General Vrevsky and Major-General Pavalo-Shveikovsky; they encouraged me in it, and promised to do all that lay in their power to render it as practicable and as easy as possible.

The route which I mapped out before starting led over the Alai Mountains by the pass of Tenghiz-bai, then up the Alai valley alongside the Kizil-su (river), climbed the Trans-Alai range, and went down by the pass of Kizil-art to the lake of Kara-kul, over that lake, through the pass of Ak-baital, and so on to Fort Pamir on the Murghab. The entire distance amounted to over 300 miles, and was divided into eighteen short day's marches, with five days extra for rest.

I hired horses from an old Sart trader at the rate of a rouble (about

2s.) a day for each—seven baggage animals and one saddle-horse for

myself. According to the agreement I made, I incurred no

responsibility for loss or injury to the animals, and was under no

obligation in the matter of feeding them or attending to them. These

duties were performed by two men, who took with them three additional

horses carrying supplies of forage.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Islam Bai of Osh

Islam

Bai from Osh

In Margelan I had appointed a jighit (Sart courier) named Rehim Bai

as my right-hand man. In addition to his experience of Asiatic

travel, he was an excellent cook, and spoke Russian. I gave him 25

roubles a month. But on this journey he came near to losing his life,

and left me at Kashgar.

When Rehim fell ill, his place was taken

by one of the two horsemen who accompanied him. Islam Bai, whose home

was at Osh, proved the better man of the two, and throughout the

entire journey served me with a fidelity and devotion which merit the

warmest praise.

The following pages will best show how great is the debt of gratitude I owe to this man. We travelled side by side through the terrible Desert of Gobi, facing its sand storms in company and nearly perishing of thirst; and when my other attendants fell by the side of the track, Islam Bai with unselfish devotion stuck to my maps and drawings, and thus was instrumental in saving what I so highly prized. When we scaled the snowy precipices, he was always in the vanguard, leading the way. He guided the caravan with a sure hand through the foaming torrents of the Pamirs. He kept faithful and vigilant watch when the Tanguts threatened to molest us.

The services this man rendered me were incalculable. Except for him my journey would not have had such a fortunate ending as it had. It gratifies me to be able to add, that King Oscar of Sweden graciously honoured him with a gold medal, which Islam Bai now wears with no small Sven Hedin, "Through Asia"

Uch-Kurgan

23 Feb 1894

Utch-kurgan is a large village picturesquely situated on the river

Isfairan, at the point where it emerges from the northern declivities

of the Alai Mountains. I was received with a flattering welcome. A

mile or two outside of the village I was met by the volastnoi (native

district chief) of the place, accompanied by his colleague, the

volastnoi of Austan, a place higher up in the mountains. The former

was a Sart; the latter a Kirghiz. Both wore their gala khalats

(coats) of dark blue cloth, white turbans, belts of chased silver,

and scimitars swinging in silver-mounted scabbards. At their heels

rode a numerous cavalcade of attendants. These dignitaries escorted

me to the village, where a large crowd had assembled to witness my

entry and enjoy the .rare pleasure of a real tamashah (spectacle).

After dastarkhan (refreshments) had been offered round, the caravan

started again, escorted by the troop of horsemen.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Isfairan Valley

26 Feb

1894

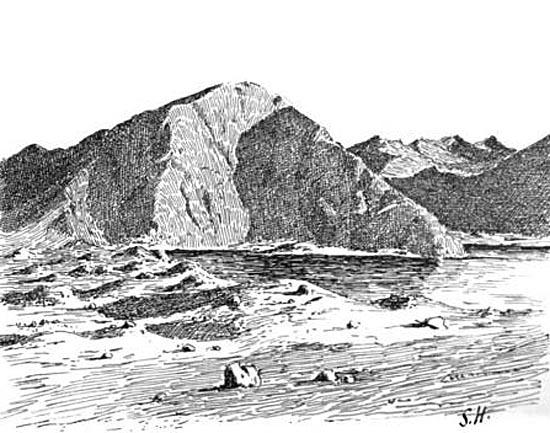

Isfairan

Valley above Austan

The valley of the Isfairan grew more sharply contoured as we advanced, and narrowed at the end to a width of only a few hundred yards. At the same time the path ascended, following in part the bed of the stream ; though in places it ran along the face of steep, well-nigh precipitous slopes. The river has cut a deep channel through the coarse-grained conglomerates, and its waters, dark green in colour, but clear as crystal, danced merrily along among the boulders.

Time after time we had to cross over the stream on wooden bridges, which sagged and swayed at every step we took. One of these was known by the significant name of Chukkur-kopriuk, that is the Deep Bridge. Seen from the lofty crest along which the path ran, it looked like a little stick flung across the narrow cleft far down below.

The first horse of the string, the one which carried the bags of straw, together with my tent-bed, was led by one of the Kirghiz guides. But, despite the man's care, when he came to this spot the animal slipped. He made frantic efforts to recover his feet. It was in vain. He slid down the declivity, turned two or three summersaults through the air, crashed against the almost perpendicular rocks which jutted up from the bottom of the valley, and finally came to a dead stop in the middle of the river. The bags burst and the straw was scattered amongst the rocks. Shrill shouts pierced the air. The caravan came to a standstill. We rushed down by the nearest side-paths. One of the Kirghiz fished out my tent-bed, as it was dancing off down the torrent. The others encouraged the horse to try and get up. But he lay in the water with his head jammed against a large fragment of rock, and was unable to respond to their exhortations.

The Kirghiz pulled off their boots, waded out to him, and dragged him

towards dry land. It was however wasted labour. The poor brute had

broken his back; and after a while we left him lying dead in the

middle of the river, whither he had struggled back in his dying

agonies. The straw was swept together, sewn up again, and packed on

one of the other horses, which carried it till we reached our

night-quarters at Langar.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Austan

24

-25 Feb 1894

In the hurry of my departure from Margelan I had forgotten one

thing—namely, a watch-dog, to lie outside the yurt at nights. The

oversight was made good in a curious way. On 25th February, whilst we

were doing the next stage to Langar, an expansion of the valley 26

miles farther on, a big Kirghiz dog, yellow and longhaired, came and

joined himself of his own accord to our troop. He followed us

faithfully throughout the whole of the journey to Kashgar, and kept

grim karaol (watch) outside the tent every night. He was christened

Yollchi, or " Him who was picked up on the road."

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Langar

26 Feb 1894

Before we reached the end of our day's journey we were suddenly overtaken by the twilight. The shades of night crept thicker and thicker together in the deep narrow gorge, choking it with gloom. But after a while the stars began to peep forth; and their keen glitter, piercing the obscurities of the ravine, gave us a faint light by which to continue our perilous journey.

I have encountered a fair share of adventures and dangers in High

Asia; but the three hours' travelling which still lay before us till

we reached Langar were, I believe, the most anxious of any I had

hitherto experienced. The first ice-slide was merely the forerunner

of others to come. They now followed one another in quick succession,

each more perilous than the last. Thus we walked, and crept, and slid

slowly on, beside the black abysses gaping for their prey

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Tenghiz-Bai Pass

27 Feb

1894

The

top of the pass

The difficulties of the road were almost inconceivable, and our labours trying in the extreme. But by dint of persevering we managed to surmount all obstacles, and came to a trough- shaped depression on the summit of the range, where the snow was fully six feet deep. A deep and narrow pathway had been trampled through the snowdrifts. But it was like a shaking bridge laid across a bog. One step off the path, and the horses plunged up to the girth in the snow; and it took all our combined efforts to dig them out again, and get them back upon the " bridge." All this occasioned serious loss of time.

At length we reached the top of the pass safe and sound, and with all our baggage intact. There we rested an hour for tea, made meteorological and other observations, took photographs, and admired the entrancing scenery.

At mid-day it began to snow. A thick mist came on, hiding everything from view, and preventing us from seeing where we were going to. One of the Kirghiz went on first and sounded the depth of the snow with a long staff.

To add to our difficulties, it began to blow a gale from the west.

The snow still continued to fall, and the mist did not lift. The

Kirghiz said that a violent snowstorm was raging up in the

Tenghiz-bai pass; we might thank our stars we had got through it in

time. And indeed it was a stroke of fortune to escape in the way we

did. A day earlier and we might have been crushed under the avalanche

; a day later and we might have been annihilated by the buran

(snow-hurricane).

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

The

Caravan in Allayi Valley

28

Feb-1 Mar 1894

Snowed-in

Allayi Valley

During the night between 28th February and 1st March the wind howled and whistled through the tent hour after hour, and at length rent several narrow slits between the separate pieces of felting. In the morning, when I woke up, the floor of the tent was braided with ribbons of drifted snow ; one of them ran diagonally across the pillow on which my head rested. But what cared I about wind and snow? I slept like a bear in his winter lair. The storm continued to rage all the next day. The wind, which blew from the west, whirled thick clouds of snow, as fine as powder, past the yurt (tent) from morning till night. In fact every minute the tent itself threatened to go, although we lashed it down with extra ropes, and supported it with additional stakes.

On the 2nd March we travelled as far as the winter village of Gundi.

But before starting in the morning we took the precaution to send men

on in advance to clear the path and trample a passage through the

snowdrifts. And fortunate we did so, for the old track was completely

obliterated by the storm. We kept as close to the

southern foot-slopes of the Alai Mountains as we possibly could.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Jan Ali Riding through the Snow

6

March 1894

Jan

Ali riding through a snow drift

Early on the 6th March we began to make preparations as if for a military campaign. Before daylight four men started on camels to trample a path through the snowdrifts. The Kirghiz told me, that some winters the snows were a great deal worse than they were that winter. Sometimes they were piled up higher than the top of the tent, and intercommunication between the auls had to be kept up by means of yaks specially trained to do the work of snow-ploughs, in that with their foreheads and horns they shovel narrow tunnels or passages through the snowdrifts.

After marching ten hours we decided to halt, although the region

around was desolate in the extreme—not a blade, not a living

creature to be seen. The men cleared the snow away from the side of a

low hill, and there stacked the baggage for the night.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Kyzil Art Pass

9 Mar

1894

pass of Tenghiz-bai, especially as we were favoured with the best of weather. Bor-doba, our last rest stop lay at such a great altitude that the climb thence to the pass, which crosses the highest ridge of the Trans-Alai, was not especially steep.

On the very highest point of the pass stood the burial- cairn of the

Mohammedan saint Kizil-art, a mound of stones, decorated with the

religious offerings of pious Kirghiz, namely tughs (i.e. sticks with

rags tied round them), pieces of cloth, and antelopes' horns. Arrived

at this shrine, my men again fell upon their knees, and thanked Allah

for having preserved them on the way up to the top of the dreaded

pass. They told me, that Kizil- art was an aulia or saint, who in the

time of the Prophet travelled from the Alai valley to the countries

of the south to preach abroad the true faith. In the course of his

journey he discovered this pass, to which he gave his

own name.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Pik Lenina 7134 m

in the

summer

Pik

Lenina in the summer

Panoramio

North Shore of Lake Kara-kul

10

Mar 1894

Lake

Kara-kul in summer

Panoramio

On the southern side of the range there was at first a good deal of snow; but it soon began to get thinner. At the end of a march of eight hours' duration we came to the little caravanserai of Kok-sai. The name of this place is indelibly engraven upon my memory. It was there I recorded the lowest temperature it has been my lot to observe in the course of all my journeyings through Asia. The quicksilver thermometer fell to - 36°8 Fahr. (-38°2 C.), that is, almost as low as the freezing- point of mercury.

South of the pass of Kizil-art the landscape changed its character entirely. There was a far smaller quantity of snow. Over large areas the surface of the earth was bare and exposed, in others buried under sand and the debris of disintegrated rocks.

The sun set at six o'clock. At the moment of his disappearance the shadows of the mountains on the west side of the plain raced across it so swiftly that it was difficult for the eye to follow them. Then they slowly mounted up the flank of the mountains on the east side, till nothing but the topmost pyramidal peaks were left glowing in the evening sunshine. A quarter of an hour later, and the entire region was dimmed with the twilight. The mountains on the east stood out like pale, chilly spectres against the background of the rapidly darkening sky; whilst those in the west were like a black silhouette thrown upon the brighter — light blue and mauve tinted—atmosphere behind them.

We halted not far from the shore of Great Kara-kul, taking sheltered

in an earthen hut, where we passed the night in warmth

and comfort.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Overnight on Karakul Island

11

Mar 1894

On the morning of 11th March I set off to cross the lake towards the south-west, taking with me a specially selected portion of the caravan, namely two Sart jighits, two hardy Kirghiz, all of us being mounted, with two pack-horses carrying the baggage. We also took with us provisions and fuel to last two days, as well as a tegher- metch (a small conical Kirghiz tent), an iron bar, axes, spades, and the sounding apparatus and line. Before leaving the rest of my people, I arranged with them to meet us at the next camping-station, not far from the south-east corner of the lake.

The Kirghiz said, the island had never before been visited by human beings. We pitched the small yurt (tent) we had brought with us, and immediately in front of the entrance made a fire of teresken faggots.

We woke up early the following morning, frozen, numbed, and out of humour. We rode across the ice about three miles due west from the island, then stopped and set about sounding the depth of the western basin.

As we moved along, every step the horses took was accompanied by

peculiar sounds. One moment there was a growling like the deep bass

notes of an organ ; the next it was as though somebody were thumping

a big drum in the "flat below"; then came a crash as though

a railway-carriage door was being banged to; then as though a big

round stone had been flung into the lake. These sounds were

accompanied by alternate whistlings and whinings; whilst every now

and again we seemed to hear far - off submarine explosions. At every

loud report the horses twitched their ears and started, whilst the

men glanced at one another with superstitious terror in their

faces.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Digging Sounding Holes through the

Ice

12 Mar 1894

Shortly after passing a little promontory, we saw before us the long fjord, or gulf, which cuts deep into the southern shore. It presented a striking picture. We cut our last sounding-hole right in the middle of the mouth of the fjord.

They went on for two and a half miles, and made another sounding-hole. When they finally reached the southeast shore it was dark, and they could not find their caravan and had to camp out another night - (a long story omitted here).

At bout six o'clock in the morning day broke, and we mounted into the saddle, hungry and stiff with cold. We rode southwards for an hour, till we came to a place where there was a little scanty yellow grass, left by the last flock of sheep which browsed over the spot in the autumn. Whilst the horses grazed for an hour or two, I and Shir got a good sleep, for the sun was up and kept us warm.

Having mounted again, we pushed on still towards the south. On the way we met a solitary Kirghiz, travelling on foot from Rang-kul to the Alai valley. As with most of his race, his eyes were as sharp as a hawk's; he had discovered us nearly two miles before meeting us.

I and Shir found our comrades at the end of another hour's riding.

Our first concern was to thaw our stiffened limbs and warm ourselves

with hot tea ; then, whilst the horses were eating their fodder, we

despatched our breakfast, consisting chiefly of mutton and tinned

provisions

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Muzkol Valley

14 Mar1894

Lake

Karakul fom the southeast.

The country rose from the Kara-kul very gradually towards the south. Before we had travelled far, we rode into a broad valley, stretching between two parallel mountain ranges, which ran north and south, and were sheathed in snow. As a rule a larger quantity of snow falls every year in this valley than around Great Kara-kul, though the depth seldom exceeds four inches. Thick clouds hung about the mountain-tops; everywhere else the sky was perfectly clear.

The valley into which we turned was the valley of Mus-kol, which led up to the pass of Ak-baital. There was but little snow on the ground ; but as we advanced, the surface became more and more thickly strewn with disintegrated debris.

Upon my arrival in camp, I was met by four Kirghiz, wearing their

gala khalats (coats). They had been sent from Fort Pamir to welcome

me, and had been waiting five days, with a tent and supplies of food

and fuel. They told me that my long delay had begun to make the

Russian officers at the fort uneasy. As a matter of fact, we had been

seriously delayed by the enormous quantities of snow we met with in

the Alai valley.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Rest on Ak-Baital Pass

16

Mar 1894

Ak

Baital Pass, 4655 m

The next day brought us a hard climb of ten hours' duration right over the Ak Baital pass, which rises to the pretty respectable altitude of 15,360 feet.

A sharp snowstorm, waxing for a time into a hurricane, gave us a

chilling welcome in the pass. The ascent was tough work for the

horses, chiefly in consequence of the extreme rarefaction of the air.

They had to exert themselves to the uttermost, and frequently stopped

to gasp for breath ; and despite our utmost care often fell. The pass

consisted of two distinct ridges, separated by a stretch of almost

level ground, which took us a good half-hour to ride over. It was

covered with snow to the depth of 12 to 16 inches. On the summit of

the pass we rested a short while. In the Ak-baital pass another of

our overworked horses fell dead. One of the Kirghiz bought the skin

from Islam Bai, the leader of the caravan, for two roubles.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

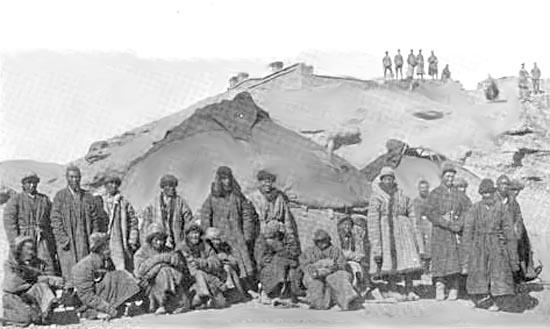

Fort Pamir1

19 Mar- 7

Apr 1894

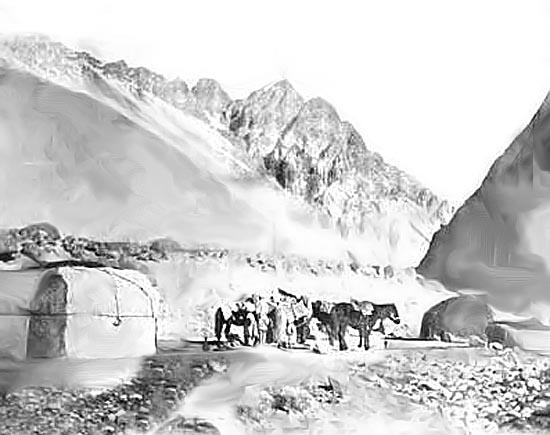

Members

of SH's caravan under Fort Pamir

On 19 March we accomplished the last stage of this portion of our long journey, namely the lower extremity of the valley of Ak-baital, and the part of the valley of the Murghab which we had to traverse to get to the Russian outpost on the Pamirs.

The first thing we noticed, upon catching sight of the fort at a distance, was the Russian flag flying from its north-west corner, proclaiming the sovereignty of the Czar over the "Roof of the World." When we drew nearer, we saw that the ramparts were beset with soldiers and Cossacks to the number of 160, drawn up in line. They gave us a cheer of welcome ; and at the main entrance I met with a hearty reception from the commandant, Captain Saitseff, and his officers, six of them in all. They conducted me to the room in their own quarters which had been ready for me a whole week. A yurt was set apart for the use of my men.

As soon as I got my baggage stowed away, I went and had a good bath, and then joined the officers at mess. It was a meal not soon to be forgotten. I delivered the greetings I had brought from Margelan. I had a thousand and one questions to answer about my adventurous ride across the Pamirs in the middle of winter.

Then, when the Cossack attendants served round the fiery wine of

Turkestan, the commandant rose, and in a neat speech proposed the

health of Oscar, King of Sweden and Norway. If ever a toast was

responded to with real sincerity and gratitude, it was when I stood

up to return thanks for the honour done to my king.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

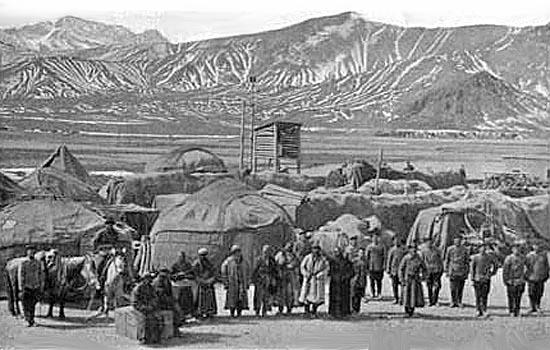

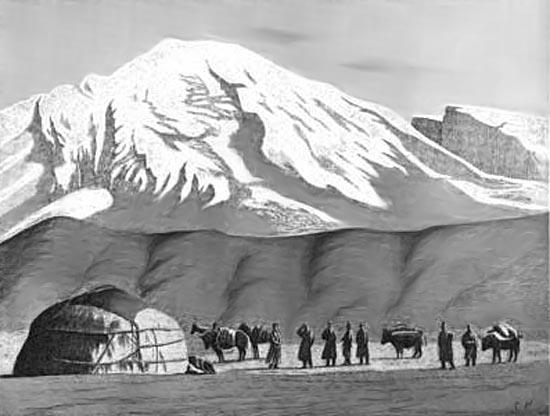

Yurts at Fort Pamir

Mar/Apr

1894

Yurts

at Fort Pamir

Fort Pamir, situated on the right bank of the Murghab, at an altitude of 11,800 feet above sea-level, was built (1893) as a check upon Chinese and Afghan aggressions upon the territories of the former Khans of Kokand.

Although the Russians conquered the khanate in 1875 and 1876, for some time they bestowed but little thought upon the region of the Pamirs. It was only thinly populated and very difficult of access, and possessed nothing to invite attention. General Skobeleff, for as far-sighted as he was, never seems to have given it a thought. But when the neighbouring powers began to stretch out their hands towards it, Russia awoke to the necessity for energetic action.

Colonel Yonnoff's famous expedition was the first result of the change of policy on the part of the St. Petersburg authorities. It was an expedition which opened up political questions of a grave and delicate character; which however were satisfactorily terminated by the labours of the Anglo-Russian Boundary Commission in the summer of 1895.

Our day was generally spent in the following manner. Every man had

tea (first breakfast) in his own room. At noon precisely a signal by

roll of drum called us all together for a substantial breakfast.

After that we had tea again in our own private quarters. At six

o'clock a fresh drum-signal reminded us that dinner was ready. After

dinner we broke up into little groups, to each of which coffee was

served round. We then talked until late into the night; and towards

midnight I and the commandant used to have a snack of supper.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Lakes Shorkul-Rangkul

I7

Apr 1894

On 7th April 1894, after partaking of a substantial breakfast, I bade adieu to Fort Pamir, though I was escorted a good distance on my way by the commandant and his officers. Arrived at the little torrent of Ak-baital, we found some of the Cossacks awaiting us with tea. Then, having thanked my Russian friends for the splendid hospitality they had shown me during those never-to- be-forgotten days—a last shake of the hand from the saddle, a last wave of the cap, and away 1 spurred towards the north, followed by the interpreter of the fort, the Tatar, Kul Mametieff, whom the commandant sent with me as a guard of honour.

Just as daylight was fading, we came to the twin lakes Shor-kul and Rang-kul, which are connected by a narrow sound. There we took up our quarters for the night, camping in a yulameika, a tall, conical tent with no smoke- vent.

Meanwhile my right-hand man, Rehim Bai, had fallen ill, and all the

way to Kashgar was totally unfitted to discharge his regular duties.

We had to transport him thither like a bale of goods on the back of a

camel. His place was taken by the man of whom I have spoken before

—Islam Bai ; and it was during this part of my journey that I first

learned to know and value that excellent man's many

excellent qualities.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Camp Fort Rangkul

11 Apr

1894

Arrival

at camp Fort Rangkul

Chuggatai Aul - First

Chinese

12 April 1894

I speedily learned that all sorts of wildly extravagant rumours were flying about the neighbourhood concerning me. It was said, that I was a Russian, coming at the head of three-score Cossacks, armed to the teeth, to make a hostile raid into Chinese territory. My arrival had therefore been looked forward to with not a little apprehension. But when the Kirghiz saw me ride up alone, accompanied by only a small band of their fellow-believers, their fears quickly subsided, and they gave me a very friendly welcome. All the same, they lost no time in sending off a mounted messenger to Jan Darin, commandant of the little Chinese fort of Bulun-kul.

The next morning therefore I was not surprised to see the emissaries of the Chinese officer ride up, bringing greetings of welcome. They were also charged to find out who I was, and what was my business. The head of the " embassy " was one Osman Beg of Taghdumbash, a fine-looking Kirghiz, with a handsome, intelligent countenance. He commanded a lanza or troop at Bulun-kul. His companions were Yar Mohammed Beg, chief of the frontier-guard stationed at Kiyak-bash, and a mollah or priest. All three wore white turbans and parti-coloured khalats (long Kirghiz coats). Their mission accomplished, they rode back to Bulun - kul, to make their report.

On the 13th April we camped only a very short distance

further.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Lake Bulung-Kul - The Mandarin

Appears

13 Apr 1894

Mustagh

Ata from our camp

On the 13th April we camped only a very short distance further. We had scarcely got our baggage stowed away, when a yuz-bashi (chief of one hundred men) came to announce that the acting commandant of Bulun- kul, the Kirghiz officer Tura Kelldi Savgan, together with Chao Darin, his Chinese colleague of Tar-bashi, a little fort at the mouth of the Ghez valley, were on the way to pay me a visit.

I had barely time to get outside the yurt, when up they trotted, with half a score Chinese soldiers at their heels. A gay spectacle they made too, with their grey trousers, shoes, and scarlet tunics, decorated with large Chinese characters in black. Every man was armed with a rifle, and rode a white horse, bearing a red saddle and big stirrups which rattled noisily.

I invited them to step inside the tent, and bade my men serve an extra dainty dastarkhan (lunch), consisting of sardines, chocolate, preserved fruits, sweet cakes, and liqueur—delicacies which I had brought with me from Margelan specially to tickle the Chinese palate. Chao Darin conceived a particularly strong affection for the liqueur, and inquired how much a man could drink without getting intoxicated. My cigarettes too met with much appreciation; although my Chinese friend Chao Darin preferred his own silver-mounted water-pipe.

Conversation was carried on between myself and the mandarin under considerable difficulties. At that time I was not sufficiently master of the Kirghiz tongue to be able to speak it fluently. I therefore expressed myself to Kul Mametieff in Russian. Kul Mametieff conveyed my meaning in the Turki language to the mandarin's interpreter, a Sart from Turfan, and he in his turn passed on the message in Chinese to Chao Darin.

As soon as they learned of my intention to make an attempt to climb Mus-tagh-ata, they objected to Kul Mametieff going with me, on the ground that he was a subject of Russia. But when I showed them my pass, and the letter I carried from Shu King Sheng, the Chinese ambassador at the Court of St. Petersburg, addressed to the Dao Tai of Kashgar, they withdrew their opposition, but stipulated that, immediately we came down from the mountain, Kul Mametieff should take the shortest road back to the Russian Pamirs.

I announced that it was my intention to return their visit without delay; but both officers declared, that they had no authority to admit a European inside the fort in the absence of the commandant, Jan Darin, who had gone to Kashgar, but would soon return.

In this laborious way we parleyed backwards and forwards for five mortal hours. When at last they rose to go, I thought to make a good impression upon them by presenting them with a Tula kinshal (dagger) and a silver drinking-cup. They protested, it was not at all the right thing for me to offer them presents after such a recherchd dastarkhan ; that it ought to be the other way on, seeing that I was their guest. But in the end they suffered them selves to be persuaded, saying they hoped to have an opportunity to return my presents when I came back from my trip up the Mus-tagh-ata. We never saw a glimpse of the gentlemen again; although they indicated their presence by forbidding the Kirghiz of the neighbourhood to furnish me with supplies of mutton, fuel, and other necessaries.

The rest of the day was spent in making preparations for the ascent of Mus-tagh-ata. I decided to take only four men with me, namely Kul Mametieff, Islam Bai, and the two Kirghiz, Omar and Khoda Verdi.

In the evening we were honoured with a visit from some of the Chinese

soldiers from the fort. They asked to be allowed to peep into one or

two of my commissariat boxes and yakhtans (packing-cases). We

afterwards learnt that up at the fort they believed all my boxes were

packed full of Russian soldiers, who in that way were being smuggled

across the frontier. The fact that each and every trunk I had was

only capable of holding at the most about one-half of a soldier did

not in any way help to allay their suspicions

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

First Ascent of Mustagh Ata

14 Apr1894

Mustagh

Ata and little Lake Karakul

It was the 14th April when we set off to climb the great

Mus-tagh-ata. A low hill in the vicinity gave us a distant view of

the Little Kara-kul (near Subashi), a beautiful Alpine lake embosomed

in deep mountains, whose reflections played upon its surface,

constantly changing its waters from blue to green and from green to

blue.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

Lake Bassyk-Kul Camp

15-16

Apr 1894

Meeting

Togdasin Beg chief of the Kirghiz of Su-bashi

April 15th. The farther we went the more broken grew the surface. We came to the little Alpine lake of Bassyk-kul, with its fantastic shore-line. A low hill in the vicinity gave us a distant view of the Little Kara-kul, a beautiful Alpine lake embosomed in deep mountains, whose reflections played upon its surface, constantly changing its waters from blue to green and from green to blue.

Here we were met by a stalwart horseman, Togdasin Beg, chief of the

Kirghiz of Su-bashi. He received me politely and in a friendly

spirit, and conducted me to his large and handsomely appointed yurt.

This man subsequently became one of my best friends amongst the many

I made in Asia.

They abandoned the climb and returned to

Subashi:

As soon as we got our tent in order, we were honoured by a stream of visitors, who kept coming all the evening. First there were all the Kirghiz of the neighbourhood. Then we had the Chinese soldiers of the garrison, amongst them some Dungans (Chinese Mohammedans). All the sick too of the valley came to me begging for medicine. One old woman said she had the Kokand sickness. Another patient suffered from toothache. A third had a pain in his nose. One of the Dungan soldiers experienced an uncomfortable feeling in his stomach when a storm was blowing. And so they went on. I treated them one and all in the same simple fashion, by prescribing for each alike a small dose of quinine. And on the principle that the bitterer the remedy the more efficacious it is—a principle which is thoroughly believed in by all Asiatics—they went away universally satisfied.

The next day we were entertained at tea by the notables of the

Kirghiz auls and by certain of the Chinese soldiers. In the evening

Togdasin Beg came to my tent by invitation, and was entertained with

a liqueur and the harmonies of a musical-box, which so enraptured

him, that he declared he felt twenty years younger. He said he had

never enjoyed anything so much since the days when the great Yakub

Beg ruled over Kashgar. Somewhere about twenty years earlier, he told

me, the Sultan of Turkey sent a large musical-box as a

present to Yakub Beg.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"

The

cemetery at Subashi

Panoramio

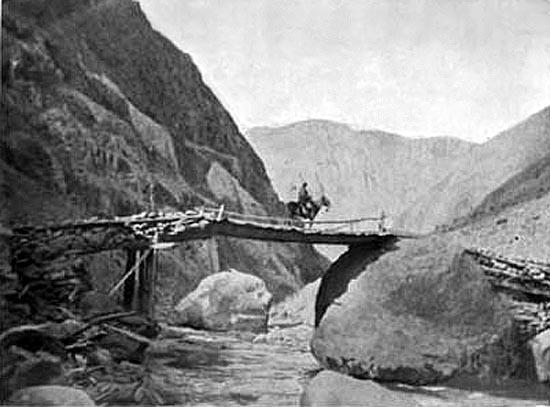

Crossing the Ghez Darya

30

April 1894

After the storm susided we pushed on towards Kashgar.

One

of the bridges over the Ghez Darya

We crossed three more small bridges, the last of them a particularly dangerous one. We narrowly escaped losing one of our horses there, which put its foot through the thin planking. The baggage having been taken off the animal's back, all hands set to work to haul him up again. That done, the men mended the bridge by filling up the hole with turf. After that we left the Ghez-daria

Kashgar 1

1 May 1894

The

garden of the Russian Consulate in Kashgar

On the evening of the 1st May we reached Kashgar. There I was warmly welcomed by my old friend Mr. Petrovsky, Russian consul-general. I remained fifty days in Kashgar, waiting till my eyes got well. This time I employed in working out the results of my journey up to that point, in arranging and tabulating my observations, and plotting out my maps. The rest was indeed very welcome, in fact absolutely necessary. I thoroughly appreciated the hospitality of my friend's house, where I was surrounded by all the comforts and conveniences of civilization. Consul Petrovsky is the most amiable man in the world, in every way a right excellent host. His intellectual conversation was as instructive as it was elevating.

During my first visit in Kashgar I had the good fortune to come in contact with two pleasant English gentlemen, the famous traveller Captain Younghusband and Mr. Macartney. The former had in the interval returned to India. The latter still dwelt in Kashgar, occupying a comfortable housen a splendid situation close to the garden of Chinneh-bagh.

Mr. Macartney was the Agent of the Indian Government for Chinese affairs in Turkestan. He had had a first-rate training, and spoke fluently the principal languages of Europe and the Orient, being especially distinguished in Chinese. In fact, he was too good for his post.

In a word, I had a splendid time of it in Kashgar. I was quartered in

a cosy little room in a pavilion in the consulate garden, and after

breakfast used to stroll backwards and forwards under the shady

mulberry and plane trees, along a terrace which commanded a wide view

of the desolate regions through which I was shortly to journey

on my way to the Far East.

Sven

Hedin, "Through Asia"