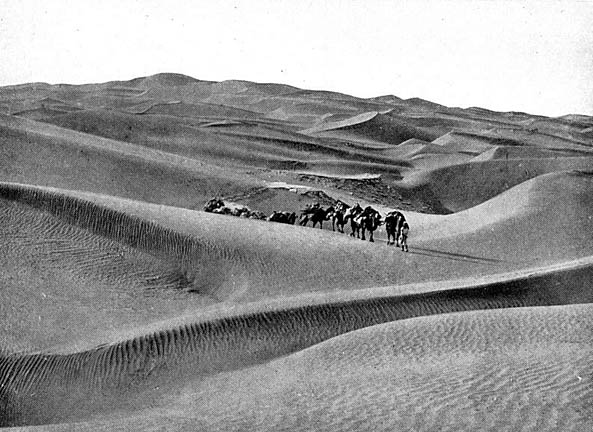

Marching through the high dunes southwest of Maralbashi

Sir Aurel Stein's Third Expedition

1913-1916

On

Google Earth

To open this map you have to download

GE onto your hard-disc

Collection of Stein's expedition maps as Google-Earth overlays (inaccurate but still very useful!)

Stein's

Third Expedition

Stein’s

third expedition to Central Asia was his longest. The

route chosen for approaching the desert was a new one, taking him

through the mountain territories of Darel and Tangir,

mentioned in the accounts of Chinese pilgrims, but never before

visited by Europeans. From Kashgar he travelled east along the foot

of the Tianshan mountain range, then across the Taklamakan desert to

the south. On route, useful antiquarian observations were made before

arriving at the oasis of Khotan in November 1913.

From there the journey to Lop Nor followed the old caravan route, allowing him to trace more remains in Domoko, Niya River, and Miran. He set out on 1 February 1914 into the waterless desert northward, moving towards Loulan, a new route.

Following the ancient border line discovered during the second expedition he arrived again at Dunhuang by the close of March 1914.

He successfully traced the border eastwards for another 250 miles to the Etsin Gol River. In May he reached Karakhoto, which he identified with the city of “Etzina”, described by Marco Polo, who had taken the same routes in the 13th century.

In June 1914, Stein had to stop his work at desert sites because of the increasing heat, turning his attention to the Nanshan range. From September 1914, he set out on a journey of some 500 miles along unsurveyed routes, right across the desert ranges of the Beishan mountain to the easternmost Tianshan range.The journey along its northern foot acquainted him with a part of Dzungaria. He excavated sites near Turfan on the northern Silk Road, especially in Astana and Bezeklik

In June 1915, Stein returned to Kashgar. Then he started a three month journey, during which approximately 1,700 miles were covered on foot and horseback across the Pamirs into Russian Turkestan. He arrived at Samarkand in October 1915. From there he reached the Persian border by rail, and travelled along the Persian-Afghan border. He reached the area around Sistan (Chistan, Sakastan) in early December 1915.

There he began a third winter’s archaeological campaign in ancient Sakastan. Among the extensive ruins of a palace on the isolated rocky hill of Koh-i-Kwaja, he discovered the remains of wall paintings, the oldest ones brought to light in Iran. Some of them, distinctly Hellenistic in style, probably dated from Parthian times, illustrating an Iranian link between the Greco-Buddhist art of north-western India and the Buddhist art of Central Asia. Another interesting discovery in the same area was that of a chain of watch towers that form an exact counterpart to the Chinese Han limes (border defenses), and date from the Parthian period.

Stein returned to India in March 1916.

From stein.mtak.hu

Because Europe was embroiled in WW I - which is only incidentally metioned - the third expedition (1913-16) was funded entirely by the Government of India. The intention was that the majority of finds from this expedition should be the foundation of a new museum in New Delhi, and that representative specimen and 'literary remains' should be presented to the British Museum (which had to wait until 1922).

To reduce the size of this webpage, I have omitted routes and places Stein described extensively on his Second Expedition in favor of emphasizing new finds at the Loulan Grave Sites, Karakhoto, the Astana Cemetery, and his traverse of the Russian Pamirs. You find them on the Google-Earth Map.

Details of this expedition are buried in the 1000 pages of “Innermost Asia”

For faster reading I recommend the comprehensive, one-volume description of Stein's travels in "On Ancient Central Asian Tracks"

Srinagar-Darel and Tangir

Valleys-Wakhan-Tashkurgan-to Kashgar

May – Sep

1913

To vary his route Stein approached Turkestan through the uncharted Darel and Tangir Valleys, crossed the familiar Baroghil Pass into the Wakhan and via Tashkurgan to Kashgar, a journey of nearly 6 months.

Kashgar

Sep 21 -

Oct 9, 1913

Kichik Beg, who had been sent from the Yangihissâr Yamên to receive me, was an old acquaintance from Khotan. He had much to tell me of the detrimental effect on the economic development of the district resulting from the disturbances and political uncertainty which followed the Chinese revolution. In spite of years of plentiful water and abundant harvests, little or no new land had been opened in this part since 1908. Fortunately no signs of such a set-back interfered with the pleasant impressions that I gathered in the course of my last forty miles' ride on September 21 to Kashgar.

Before nightfall I had the satisfaction of arriving at the British

Consulate General, and enjoying once more the kindest welcome under

the ever hospitable roof of my old friend Sir George Macartney.

The

two busy weeks spent in Kashgar would certainly not havé sufficed

for all the heavy work which the organization of my caravan and other

arrangements involved, had not the ever helpful care and unfailing

influence and provision of Sir George Macartney aided my efforts in

every direction. The rapidity of my movements, since I left Kashmir

in May 1913, had been directly prompted by the wish to secure a

timely start for the explorations of the autumn and winter. I knew

well from previous experience the importance of securing suitable

transport at the outset if this the success of the operations in the

desert were to be secured. I therefore felt special satisfaction

when, as a result of arrangements made months before, twelve fine

camels arrived from far-off Keriya, bred for desert work.

I had been delighted to see again at Kâshgar my devoted Chinese

assistant and friend, Chiang Ssü-yeh, whose efficient aid had

constantly proved so valuable on my second journey. He had well

deserved the reward of being appointed in 1908 Chinese Munshi at the

Consulate General. Notwithstanding that he held this comfortable

berth, he would, I believe, have gladly rejoined me for another long

and trying journey, had not his increasing years and a serious aural

affection warned me against accepting the sacrifice and risks that

such a step would have involved for him. Li Ssü-yeh, a young man,

weakly and shrivelled up, whom Chiang provided for the post as my

camp literatus, came like himself from Hu-nan, but turned out

to be a poor substitute, as I had apprehended from the first. But

there was no other choice then at Kâshgar. Wholly absorbed in

treating his ailments, real and imaginary, with every quack medicine

and taciturn and inert by nature, Li was useless for the many

scholarly as well as practical labours in which Chiang had always

been ready to engage with cheery energy and keen interest. We did

whatever was possible to spare poor Li Ssû-yeh all needless fatigue

and exposure while travelling. Anyhow he was brought back safely to

Kâshgar some twenty months later, managed meanwhile to indite my

Chinese epistles, and justified Chiang's belief in his probity by

never playing me false in my dealings with Chinese

officials.

Innermost

Asia

The New Republic of China

The New Republican Era of China had begun with the outbreak of an uprising on October 10, 1911 in Wuchang, the capital of Hubei Province. The formation of the Republic of China put an end to the Manchu, Qing Dynasty and over 2,000 years of Imperial rule.

Stein describes the situation he found

in 1913 which would repeatedly interfer with his movements:

The

peace of the New Dominion had in 1912 been seriously disturbed by a

series of assassinations of Mandarins, including the Tao-t`ais of

Kâshgar and Aksu, and by petty outbreaks among the Chinese garrisons

and their attendant rabble fomented by unscrupulous office-seekers

masquerading as `revolutionaries' and `reformers'. Though confined

entirely to the numerically weak Chinese element and viewed at first

by the mass of the people, peaceful Turki Muhammadans, with their

characteristic unconcern, these disturbances before long spread a

feeling of insecurity throughout the province.

The situation had

become more settled by my return to Kâshgar in 1913 under the

influence of a somewhat stronger régime: local administrators were

now less subject to officials' exactions of blackmailing.

Innermost

Asia

From Maralbashi to Khotan

Oct

25, 1913

Stein decided to follow the Northern Route as far as Maralbashi and from there to march southeast until he would reach the Khotan river near Mazar-tagh in an attempt to explore Hedin's fateful desert strip.

Marching

through the high dunes southwest of Maralbashi

On October 25th I set out from Marâlbâshi for my long-planned expedition into the desert south-eastwards. Its object was to reach the Mazâr-tâgh range on the Khotan river, if possible, directly through the sands of the Taklamakân.

I was under no illusions as to the serious difficulties that a march across absolutely waterless ground covered with high dunes, to a point more than 130 miles distant, would present. Its risks were sufficiently illustrated by Dr. Hedin's experiences during the bold journey that he undertook, starting towards the end of April, 1895, from the same ground and making his way through the sandy wastes eastward. It had ended in the destruction of his caravan and his own narrow escape from death.

In order to guard against the dangers to which this disaster had apparently been largely due, I had taken care to choose a cooler season and hence far less trying to men and camels. To assure the provision of an adequate supply of water and to lighten the loads of each animal as much as possible I acquired an additional 12 camels.

Change of Course: Along the Yarkand River to the

Mazar-Tagh

Nov 2 – 16, 1913

In view of Dr. Hedin's experience farther north and of what Kasim

Akhi reported about the sand formations around the Khotan Mazar-tagh,

there was little hope of gaining easier ground until we reached that

hill range itself. And worst of all, there was no assurance that,

however carefully our bearings might be taken, the route followed

would actually allow us to sight that conjectured north-western

extension of the low hill range which I was anxious to trace in the

Taklamakân; for previous experience had taught me only too well the

impossibility of steering an exact course amidst high sands by the

compass.

Ascending then the highest dune near our camp and

carefully scanning the horizon eastwards with my glasses I saw

nothing but the same expanse of formidable sand ridges, which

resembled the huge waves of an angry ocean suddenly arrested in

motion.

So there remained no choice but to turn and reach the Khotan river and the Mazartagh by way of the Yârkand river. It was a hard decision to make, and the knowledge that the little band of hardy men with me would have willingly shared what risks and adventures lay ahead did not help to lighten it. But experience proved the wisdom of having bowed to necessity in time; for on the next day there sprang up a violent sandstorm, the first of the autumn, most trying by its bitter cold even where fuel was abundant.

Baulked in my attempt to strike for the Khotan at Mazàrtagh straight

through the Taklamakân, I decided to reach it by the nearest

practicable route along the Yarkand and Khotan rivers. By the third

day of our return march from amidst those formidable sand `Dawans' we

had gained the east flank of the Chok-tâgh, where fortunately a bare

stony `Sai' offered easy going. It was doubly welcome in the blizzard

that had met us just as we got clear of the dunes. Crossing thence a

last offshoot of the Chok-tagh, we gained the Yarkand river near a

water-mill. There we forded the river, and after a long day's tramp

through the luxuriant riverine jungle of the left bank were so lucky

as to secure ponies from grazing grounds of Chigan-chöl. They

enabled me to push ahead of our camel caravan, with which I left the

Surveyor, and by four rapid marches (November 5-8), through hitherto

unsurveyed jungle tracts, to reach the extreme southwestern edge of

the cultivated zone of Aksu.

Innermost

Asia

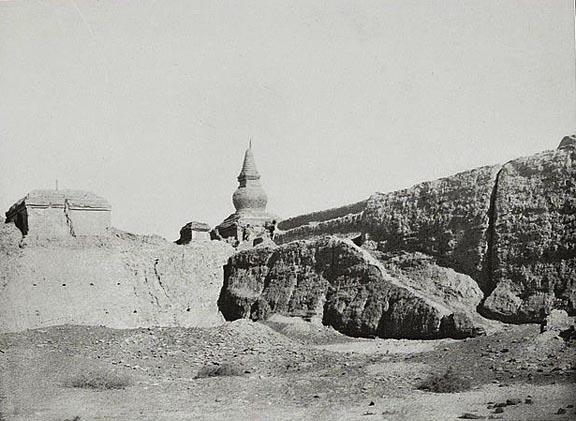

The Hills of the Mazartagh

Range

Nov 16-17, 1913

The

Tibetan Fort on Mazartagh

The distance to the Mazartagh was covered in four long marches. These were made rather trying by the bitter cold, as much as 34 degrees Fahr. below freezing-point combined with a cutting wind and a grey dust-laden sky.

I had to abandon my intention of surveying the Mazartagh range

farther into the desert north-westwards owing to the heavy strain

that the long series of forced marches had put upon our camels and

men. Nor could I allow them a preliminary rest here without a loss of

time of which the programme of the winter's explorations far away to

the east did not permit.

November 17th was devoted to a fresh

examination of the ruins on the top of the Mazârtagh.

I then

hastened ahead to Khotan by the direct route that I had followed in

1908, and covered the distance of close on 120 miles in four

days.

Innermost

Asia

Khotan

Nov 21-27,

1913

On November 21st I regained my old haunts at Khotan, and there, to my pleasant surprise, found Sir George Macartney just arrived on an official tour from Kashgar.

I was obliged to make a short halt at Khotan town for various

purposes, among others to provide winter equipment for my large party

and to raise a sufficient quantity of silver to meet all financial

needs until my arrival next spring in distant Kan-su. Moreover, a

rest was needed by all, both men and animals, who had shared the

hardships of our desert expedition. I employed the six days' stay to

gather such antiques as my ever-willing old friend Badruddin Khan,

the Ak-sakal of Indian and Afghan traders, and the ` treasure-seekers

' dispatched by him, had collected from Yôtkan and from desert sites

in the vicinity of the Khotan oasis.

Innermost

Asia

Niya Site

Dec 13

-18, 1913

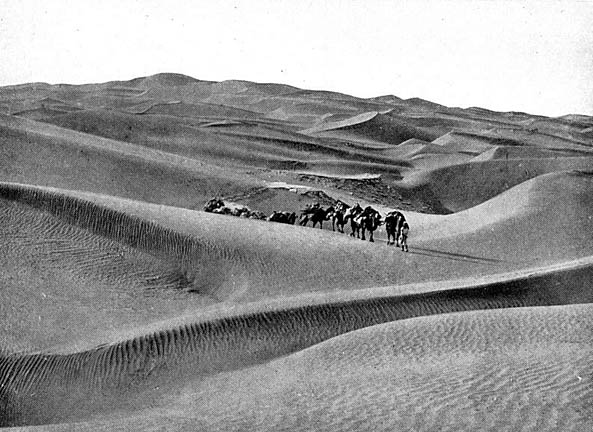

Stein's

campsite at Niya, Dec 15, 1913

Stein finished digging up two buildings and a footbridge that he had

discovered in 1906. No great treasures were found otherwise.The

photograph of his tent near the ruins is priceless.

Innermost

Asia

Miran Site

Jan 17

-Feb 1, 1914

What had irresistibly drawn me back to the ruins of Miran ever since I had left them to their solitude seven years earlier, was the thought of the fine paintings I had then been obliged to leave behind on the inner passage walls of shrine M. The full description given of them in Serindia, together with the photographs reproduced there, I will explain the exceptional interest attaching to these remains of quasi-Hellenistic pictorial art discovered in a Buddhist shrine on the very confines of China.

I discovered at once on my renewed visit on January 17th, I had failed to secure its object. In the southern hemicycle of the rotunda passage I found that the outer wall which had shown the fine fresco frieze with the representation of the Vessantara Jàtaka story and, below it, the fascinating cycle of portraits set between festoon-carrying amorini, had been laid bare and the once painted plaster surface, where not broken off, had been completely effaced through exposure.

Part

of the frieze of 'armorini' rescued from the rotunda of shrine M

The Lopliks of Miran asserted that this was the result of the operations carried out three years earlier by a Japanese traveller (obviously Mr. Tachibana), who coming from the direction of Turfan had spent a few days at the site and carried away with him to Tunhuang what fragments of painted plaster he succeeded in detaching.

Thus it took fully twelve days' work at high pressure before, on the eve of my departure from Miran, the task of rescuing what was left of these fine remains of Buddhist pictorial art was finally completed. However much I must regret the loss caused by the circumstances which had prevented my undertaking that task immediately after my discovery of the frescoes, the experience now gained conclusively proved that I had then correctly gauged the technical difficulties involved and the time it would have taken to overcome them. The fragments of stucco sculpture in shrine M were the only direct archaeological interest that the complete clearing of the ruined shrine yielded.

The thirty camels I had succeeded in collecting (with the help of an Afghan trader) were by no means too many for the large amount of stores and baggage to be carried. On our journey to Loulan we had to take sufficient ice to assure minimum allowances of water for thirty-five people for at least one month, and food supplies for one month for all, and for an additional month for my own people.....

But apart from these cares I had another source of serious anxiety during these days. Within a week of my arrival at Mirân I received a letter from Sir George Macartney bringing grave news. From the head-quarters of the provincial Government at Urumchi an edict had issued ordering all district authorities to prevent us from carrying out any surveying work, and in case of any attempt to continue our explorations to arrest and send us under escort to Kashgar `for punishment under treaty'. There is no need to discuss the probable motives of this intended obstruction, or how far the alleged regulations by the General Staff of the Chinese Republic quoted in explanation

Evening after evening as I came back from the day's work at the site I looked anxiously among the indolent Lopliks at the hamlet for the first signs of the passive resistance to my plans which their natural lethargic temperament would have made it so easy to practise. Yet the expected prohibition from Charkhlik never came. That I owed this lucky escape to an opportune `revolutionary' outbreak became clear to me only later. It had disposed of the original district magistrate whose report on Lai Singh's surveys as secret operations had been responsible for Macartneys's warning.

The

camels ready to carry the murals to Kashgar

On January 31, all that was needed for the move was safely collected.

On the same day the safe packing of the recovered mural paintings was

completed and their convoy was ready to start for the long journey

westwards. But what cheered me most was the prospect of soon reaching

that forbidding waterless desert where I should feel myself

completely protected from any risk of human interference.

Innermost

Asia

Loulan

Feb

7-24, 1914

Packing

the camels with ice blocks for drinking water

The immediate object of my return to the Loulan Site, L'.A., was to search its vicinity for such further ruins as might have escaped us on my visit seven years before, owing to want of time and the deceptive nature of the ground in this wind-eroded desolation.

In addition, it was to the east and north-east that I was

particularly anxious to have a search made for any clue to the line

followed by the ancient Chinese high road coming from the side of

Tunhuang.

Numerous finds

from Rubbish heaps

Stein's Move

North

Site of Ancient

Loulan

Loulan Graves

Feb

15, 1914

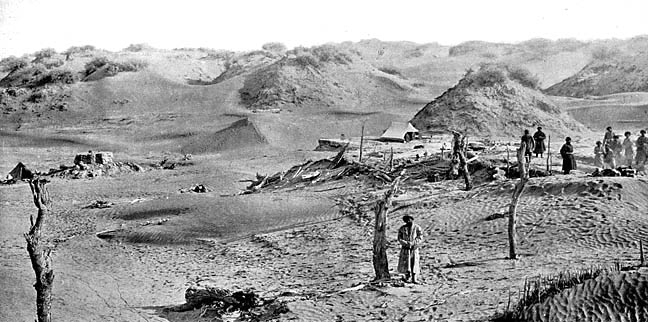

The reconnaissance reports had led me to expect here merely such relics as wind-erosion might have spared. I was therefore all the more delighted to find on the first rapid inspection that the summit of the Mesa north of Loulan retained a number of graves, apart from those on its edges, quite untouched by that destructive agent. They were all marked by rough tamarisk posts fixed, as subsequent examination showed, around the edges of the graves or pits, while the latter themselves were covered with layers of reeds almost entirely exposed.

Opening

the first grave

Until the heavily laden men arrived I had to be content with

examining such relics as the partially eroded graves on the edge of

the terrace disclosed. My

hopes were abundantly fulfilled as soon as the arrival of my diggers

made it possible to start the clearing of the graves, first where

they lay near the edge of the Mesa top and then about its

centre.

Innermost

Asia

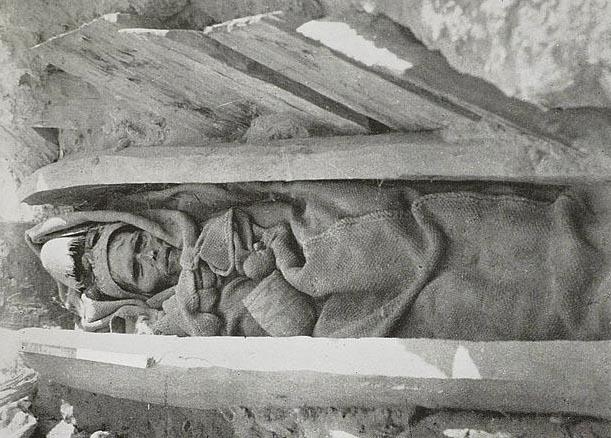

Shrouded

naturally mummified man in his grave box

Here my eye was caught at once, amidst human bones and broken boards from decayed coffins, by some rags of beautifully woven silk and wool fabrics. Their brilliant colours were excellently preserved, even where the crumbling away of the steep slope of clay had left them lying on the surface, exposed to sun and wind. Their survival under such conditions seemed a particularly encouraging augury.

|

|

|

|

Parts of shrouds from the Loulan Graves

Hermes

with the staff of Aesculap, which must have come from Gandhara or

even further west.

Judging from the dated Chinese documents recovered at Loulan, the

years A.D. 263-70 were the period when the ancient desert route and

its western terminal station saw for the last time abundant traffic

and activity.

Innermost

Asia - Fabrics

The Ancient Chinese Loulan

Road

Feb 24 -Mar 14, 1914

After replenishing our ice supply and taking a carefully arranged store of fuel, we started on February 24 for our respective tasks. The one allotted to Lal Singh was to survey the unknown north-east shores of the great salt-encrusted basin representing the dried-up ancient Lop sea-bed. I myself, accompanied by Afrazgul, proposed to search for the ancient Chinese route where it left the edge of the once inhabited Loulan area and to trace it over whatever ground it might have crossed in the direction of Tunhuang.

There remained the problem how to hit the line of the ancient route and to track it onwards through ground which all through historical times had been more barren, perhaps, than any similarly large area of this globe. For a careful search of any relics left behind by the ancient traffic there would be no time. Much if not most of the object in view had to be left to good fortune, together with what hints I could deduce from previous observations. Fortune served me better than I had ventured to hope.

Crossing

the old Lopnor seabed

The last traces of dead vegetation marking the termination of the ancient delta had long been left behind when we suddenly found the old route-line plainly marked by 200 odd Chinese copper coins strewing the dismal ground of salt-encrusted clay for a distance of about thirty yards. They lay in a well-defined line running from northeast to southwest.

I was just preparing to climb a prominent Mesa which had served as our guiding-point and to use it as a look-out, when a fortunate find on its slopes of Chinese coins and a collection of metal objects, including a well-preserved iron dagger and bridle, showed that it had evidently served as a halting-place on the ancient route. So I at once decided to head straight eastwards for that bed, and the crossing effected next day proved that I had been rightly guided.

As subsequent surveys showed, we had crossed the forbidding salt seabed at its very narrowest point, and had thus escaped a night's halt on ground where neither beast nor man could have found a spot to rest in comfort. I had the satisfaction to find the ancient Chinese road still in one place plainly marked. (See the Google-Earth Map)

I now had to turn south to Tunhuang or Sha-chou, the `Town of the

Sands', as its alternative name of later origin appropriately calls

it.

Innermost

Asia

Dunhuang Magao Caves

Apr

2 - 8, 1914

In spite of the revolution which had since my former visit replaced the Chinese Empire by a republican régime, nothing appeared to have changed in the ways of quiet somnolent Tun-huang, that westernmost outpost of true China.

What occupied my mind most during those days at Tunhuang was the thought of the famous cave-temples of the `Thousand Buddhas' southeast of the oasis and of the walled-up chapel where in 1907 I had been fortunate enough to secure such abundance of ancient manuscripts and pictorial remains from a great hoard hidden away early in the eleventh century.° I knew well that so rich a trouvaille was not to be expected now. Yet I felt sincere gratification when on the very morning after our arrival at Tun-huang my earliest visitor proved to be Wang Tao-shih, the quaint little Taoist monk, whose pious zeal had brought about the first discovery of the hoard. For his discreet consideration when it came to making its treasures accessible to research, I had every reason to feel grateful.

When, a year after my own visit, Professor Paul Pelliot had gained access to, and searched, what remained of the hoard, with all the advantages offered by his great Sinologue knowledge, he carried off a considerable selection of its manuscript treasures via Peking. The attention of the authorities at the capital had thus been attracted to the old library, and its transfer there was decreed. Of the careless and in reality destructive fashion in which the order had been carried out, I had received an inkling already at Kashgar and Khotan.

Wang Tao-shih, with a bitterness only too justified, explained how, on the arrival of the order transmitted from Lan-chou Fu, the collection of manuscripts from his jealously guarded cella had been carelessly bundled into six carts and carried off to the Tun-huang Hsien Ya-mên. The packets of Chien-fo-tung rolls that I was subsequently able to rescue by purchase at Su-chou and Kan-chou clearly showed that such pilfering had continued en route as the carelessly guarded convoy slowly made its way to distant Peking.

There was accordingly special reason to feel satisfaction when Wang Tao-shih's cordial invitation to the `Thousand Buddhas' was, on the occasion of a further visit, supplemented by a discreetly conveyed hint that his store of old manuscripts was, notwithstanding all that had happened, not yet altogether exhausted. I could feel sure that he would be there in person to show me what he had managed to save from well-meant but hopelessly inefficient official interference, and not merely the big new shrine, hospice, &c., which he proudly claimed to have built with the silver `horse-shoes' received from myself.

Wang Tao-shih welcomed me cheerfully and showed with genuine pride the various new structures which his pious activity had created since I had last seen the sacred spot seven years before. Opposite to the cave-temple in which the great hoard of manuscripts and paintings had come to light, there rose now a spacious guest-house and a series of shrines filled with big gaudily painted stucco images. Near by, a garden well laid out with young fruit trees, rows of tables, brick-kilns, &c., attested the little priest's single-minded ambition to restore, according to his lights, the glory and popular attractions of the ancient sacred site. He told me that the new hospice had been built mainly with the gifts of silver made by me in 1907 in return for the 'selections' I had then been able to carry away.

I managed in the end to arrive at a mutually satisfactory arrangement. For a total donation of five hundred Taels of silver he agreed to transfer to my possession the 570 Chinese manuscript rolls of which his reserve store was found to consist. Their total bulk is sufficiently indicated by the fact that their transport required five cases, each as large as a pony could conveniently carry.

In 1920 these rolls, together with the other manuscript materials

recovered in the course of my third journey, reached a safe place of

temporary deposit at the British Museum.

Innermost

Asia

In 1906-08 Paul Pelliot had been in Tunhuang and photogarphed the

wall paintings and sculptures of 600 odd caves. His collection was

published in 1920-24. A facsimiliy edition in 6 volumes is found at

Les

Grottes de Touenhouang

Along the Han Limes via Anhsi and

Suchou-Jiaguan to Mao-Mei

Apr 14-May 14, 1914

Stein explored the eastern part of the Han Limes. - Today there is a

road, S 314, following the towers with innumerable Panoramio photos

in GE.

Innermost

Asia

Mao-Mei

May 14

and Sep 2-4, 1914

The advance of the season and the increasing heat, from which our

camels had already begun to suffer, made it imperative to push on

down the Etsin-gol and Karakhoto. It was therefore doubly gratifying

that, thanks to the help of Mr. Chou Lua-nan, the youthful Hsien-kuan

of Mao-mei, we were able, during a single day's halt on May 14th, to

hire the additional camels required to lighten the loads of our own

animals

Innermost

Asia

Sep 2-4 1914, Return to Maomei on his way north

Innermost

Asia

Karakhoto

May 26

- June 5, 1914

The

Walls of Karakhoto still extant today

The most striking ruins of Khara-khoto, the Etsina of Marco Polo, are its circumvallation. The walls are built of stamped clay and reinforced by a wooden framework of which the big rafters could be traced in three rows all round the inside faces of the walls. But in most places their position is marked only by the holes which the decayed timber has left. The walls are about 38 feet thick at the base, but show a considerable inward slope so that the width at the top, about 3o feet from the ground, is only 12 feet. With the massive solidity of the circumvallation and its comparatively good preservation the utter decay and consequent emptiness of the interior of the town presented a striking contrast.

Among the deposits of rubbish, composed mainly of stable refuse, chippings of wood, broken pottery, &c., those found along the sides of what appeared to have been the chief thoroughfares were the largest. Among the records thus recovered, those in Chinese were by far the most numerous, and so far as appeared from a hasty examination at the time, all, with the exception of some printed pieces, were hand-written.

A rough inventory prepared before the submission of the Khara-khoto

material to various collaborators shows a total of some 230 Chinese

documents and fragments from this source, as against 57 pieces in the

Hsi-hsia or Tangut script, close on half of these being printed. The

presence of Hsi-hsia pieces, both written and printed, suffices,

however, to prove that the town must have been inhabited during the

period of the Hsi-hsia dynasty (A. D. 1032-1227), as its founder is

known to have first introduced that script. But its occupation, so

far as this documentary at present goes, might well have continued

also long after the destruction of the Tangut kingdom by Chingiz Khan

in 1227.

Some quasi-palaeographical interest attaches to the fact

that of the remains of Hsi-hsia and Chinese texts, whether written or

printed, almost all are of the oblong book form, which, originating

from the 'concertina ' arrangement of leaves illustrated by later

Chinese manuscripts from the Chien-fo-tung hoard, has been in regular

use for block-printed literary products in China since the early Sung

period.

The western portion of the town appeared to have been mostly occupied by shrines. But among these only very few retained more than the foundations of their walls or outlines of platforms.

The rapidly increasing heat made work at Khara-khoto very trying both

for the men and for the camels, upon which we depended for the

transport of water. So I was glad when, our work at the site being

completed and Lai Singh having returned from his survey towards the

terminal lake basin, I was able on June 5th to move my camp back to

Tsondul on the Ikhe-göl and there to arrange for our journey south

to the foot of the Nan-shan.

Innermost

Asia

Marco

Polo and the history of Karahhoto

Kanchou-Zangye

July

and Aug 2- 22, 1914

Seven years later, in the summer of 1914, my third expedition brought me once again to the large city of Kanchou and the great oasis at the foot of the Nanshan of which it is the centre, just as in the days when Marco Polo stayed there. It was to serve as our base for the new surveys which I had planned in the Central Nanshan. Their object was to extend the mapping which we had effected in the high mountain near the sources of the Suloho and Suchou rivers by surveys of the high ranges farther east containing the headwaters of the river of Kanchou.

The Aborted Nanshan Survey

A serious riding accident

July 12 - Aug 2, 1914

Accompanied by the two surveyors I had tramped on for fourteen miles by the track leading above the left bank of the O-po-ho, when we were brought up by a side stream swollen by the rain and too deep to be crossed without mounting. There I met with a very serious riding accident which might well have put an end for ever to all my travelling. My Badakhshi stallion, my regular mount all the way from Kashgar and ordinarily a quiet enough animal, probably excited by the many brood mares we had passed on the march, began to plunge as soon as I had mounted, reared suddenly, and overbalancing himself fell backwards upon me. Had it not been for the sodden condition of the turfy soil, the weight of the tall animal would probably have badly crushed me.

Even so the result was serious enough. Apart from bad bruises the

muscle of my left thigh was severely injured, the main muscle

evidently torn. Walking at once became impossible, and the pain made

even carriage on the linked arms of my two surveying companions

impossible. With my leg badly swollen and other injuries, any

movement even on my campbed was for some days most difficult. But I

soon diagnosed that my limbs had luckily escaped fracture or

dislocation. By the first week of August I had sufficiently recovered

from the accident to get myself carried down in an improvised pony

litter to Kanchou, my leg still feeling severely the strain. During a

ten days' halt there in my peaceful temple quarters I experienced

much kindness from Fathers Van Eecke and De Smedt of the Belgian

Mission

Innermost

Asia

Peishan Traverse from Maomei to

Barkul

Sep 3 - Oct 4, 1914

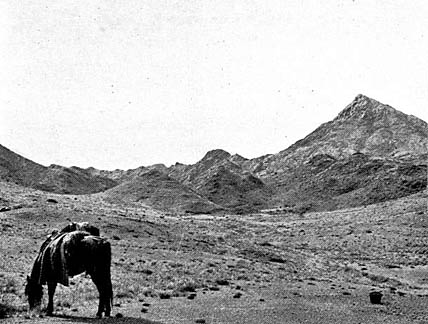

The

desolate landscape of the Peishan

This was Mongol territory who were highly defensive towards intruders. In addition Stein had hired two Chinese-speaking guides, who claimed to have travelled the route, but led his carvan repeatedly into dead-end valleys. - The following excerpts were selected to show the desolateness and monotony of the terrain. --

From Maomei a perfectly open plateau stretched away to the north-west, sloping up gently in that direction and sending its dry drainage beds down towards the northeast. On the gravel surface; bare but for scanty tufts of scrub, the caravan track showed up clearly and allowed us to cover with ease a march of close on 25 miles to the well of the Nan-ch'üan.

Our march of September 9th took us, after we had proceeded about 13 miles, across the crest of another gently rising and much broken hill chain, at an elevation of about 5,300 feet.

On September l0th a short march took us first over an utterly bare plain of gravel, where only strips of detritus 10 to 15 feet high marked the position of low ridges completely decomposed.

A day's rest by the springs and luxuriant reed-beds of Lo-Co-ch'üan was a boon to men and beasts alike. Then on September 13th we set out to the north-west on a march which proved distinctly interesting. It took us first over a bare stony Sai covered with the detritus of ridges that had almost completely worn away. After passing several dry beds, all descending from the west, we entered a region of low rocky hillocks, 20 to 30 feet high and of rounded forms, rising above the sea of detritus. There could be no doubt of their igneous origin.

The defile through which the ascent led on the morning of September 14th narrowed rapidly; it lay between rocky hills, much worn and picturesque, rising to heights of 300 to 500 feet above the valley bottom.

September 16th an easy march of about 16 miles to a well that a Chinese-knowing Mongol had spoken of as Liu-kou.

The apparent nearness of our immediate goal, on the route from Su-chou to Hâmi, induced me to pass the small patch of vegetation that the Mongols had mentioned to us under the name of Yen-chi and to push on.

At the foot of the hills we stumbled on a dry stream-bed with a big cairn showing above on the sky-line. Some coarse grass was found near the bed, and there we halted for the night, after having covered a distance of 32 miles. The camels did not arrive till next morning, some of the animals having broken loose and strayed, and the men sent to search in the neighbourhood found only a square walled enclosure in ruins, but neither well nor fuel. The gale had somewhat abated in the evening; yet the bitter cold kept most of us awake that night. At daybreak our hapless `guides' discovered the well of Ming-shui about a mile away.....

We finally reached Barkul after four weeks of struggle on October 4,

1914

Innermost

Asia

Turfan

Oct 25 -

30, 1914

My arrival, on October 25th, 1914, close to the town of Turfân

marked the beginning of the season that I proposed to devote to

archaeological and geographical labours in the Turfân

basin.

Innermost

Asia

Kara-khôja – Gaochang

Nov

1 - 14, 1914

|

|

|

On Nov 1 I moved my camp to Kara-khôja, which, by its conveniently

central position offered an easy access to a series of important

sites. My first stay at Karakhôja, which extended to November 14th,

was mainly taken up with a series of preliminary tasks connected both

with our archaeological and our topographical work. I paid

preliminary visits in succession to the cemetery sites near Karakhöja

and its large sister village Astâna, and to the cave-shrines of

Toyuk and Bezeklik.

Innermost

Asia

Toyuk

Nov 23 -

Dec 13, 1914

On November 23rd I returned to Toyuk and camped during the next fifteen days at that most picturesque of all Turfan localities. During this halt I devoted as much time as my other duties would allow to the work which my previous reconnaissance of the often-searched and plundered ruins of Toyuk suggested as still worth undertaking.

Ceiling

of the flat-shaped dome over the cella.

I was therefore obliged to confine my own work to those few spots

where heavy accumulation of debris or other difficulties of the kind

appeared to have deterred the diggers, and to the rescue the chief

object of interest that had survived in this shrine: the painted

ceiling of the flat-shaped dome over the cella.

The ground of the

painted ceiling was formed of a fairly hard plaster, mixed

cement-like with small pieces of gravel. Small wooden pegs driven

into the rock served to secure this plastering. The removal of the

whole painted ceiling was the only means of saving this fine piece of

decorative art from risks of further destruction. Owing to the

position and the hardness of the plaster, this operation offered

considerable practical difficulty, which, however, was successfully

overcome by Naik Shamsuddin's skill and devoted care. Only when the

twenty-one panels in which the painted surface of the ceiling was

removed shall have been set up once again at New Delhi in their

proper position, will it be possible to render a full account of this

remarkably graceful composition.

Innermost

Asia

Emergency Trip to Urumchi

Dec

18, 1914 - Jan 3, 1915

The journey along the high road from Turfân town to the provincial headquarters in Urumchi and back, together with a week's stay in Urumchi, occupied my time between December 18th and January 3rd. The rapidity of the marches by which the distance of some 115 miles between the two places had to be covered, shed light on the difficulty I still experienced in walking. I hoped to obtain advice as regards my injured leg from the medical officer attached to the Russian Consulate at Urumchi ; though slowly improving, its condition still continued to be a cause of anxiety and impediment. But even without this personal motive I should have felt obliged to undertake this journey for quasi-diplomatic reasons.

Notwithstanding the helpful intercession from Peking secured in the

spring by the British Minister, I had reason to apprehend that the

spirit prompting the official obstruction, which in November had

seriously threatened to bring both my archaeological and geographical

work to a standstill, had by no means disappeared from provincial

head-quarters. As the sequel showed, this apprehension was only too

justified. In order to guard against this risk, or at least to delay

the resumption of obstructive tactics, it seemed clearly advisable to

endeavour by a personal visit to secure a more favourable attitude of

those in power at Urumchi, and in any case to assure myself of that

friendly support of Pan Ta-jên which had proved so helpful in the

course of my first two journeys.

Innermost

Asia

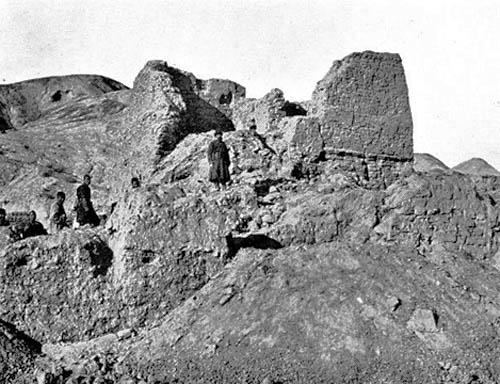

Murtuk

Dec 9,

1914 - Jan 17, 1915

Ruins

at Murtuk before excavation

After my return from Urumchi, on December 9th I left Toyuk and moved

my camp past the oases of Su-bâshi and Sengim north of the outer

hill range to the village of Murtuk. My renewed stay at Murtuk

extended to January 17th and was devoted mainly to the closer

examination of the Bezeklik shrines and the selection of additional

frescoes for removal. During these days I was also able to make a

survey of the several small groups of ruined Buddhist shrines

situated at the mouths of the little valleys that descend towards the

deep-cut e Yar' of Murtuk from the bare hills to the south-west and

south of the village.

Innermost

Asia

Bezeklik

Dec 9,

1914 - Jan 17, 1915

Bezeklik,

Buddha from a Paranirvana scene

I had previously made a reconnaissance from Karakhôja to the many cave-temples and shrines of Bezeklik. This visit had shown me that those shrines still retained a great portion of their wall-paintings. But it had also afforded unmistakable evidence of the increased damage which the pictorial remains of this, the largest of the Buddhist sites of Turfân, had suffered from the hands of local vandals since my first visit in November 1907.

A year before that (1906), Professor Grünwedel had stayed a two months at the site and devoted all his archaeological care and expert iconographic knowledge to the complete excavation and study of its remains. Many of the most interesting specimens of the paintings on the walls of the Bezeklik temples were then removed by A. von Lecoq for safety to the Ethnographic Museum of Berlin, as had been, two years earlier, the remarkably well preserved fresco panels of the shrine which Professor von Lecoq had found filled with debris and had cleared before Professor Grünwedel's return to Turfân.

With the sad proofs of progressive damage before my eyes, I could feel no doubt that removal offered the only means of assuring their security. This was the important task which brought me now to Murtuk, and to which I devoted the greater part of two successive stays of an aggregate length of fifteen days.

Astana Cemetery

Jan

19 - 31, 1915

Our work at the Astâna cemeteries was begun on January 19th with the examination of tombs which, without showing an enclosure of embanked gravel, might yet, by their arrangement in more or less parallel rows, be recognized as a separate group marking the extreme north-eastern extremity of the area. Among this group, Ast. 1, which comprises a considerable number of tombs had manifestly been searched in recent years. But in the middle row the majority appeared to have escaped.

The fabrics which clothed the dead, plain cotton and snuff-coloured

silk, had rotted away into shreds. But the mask-like covers of silk

placed over the faces had survived better and revealed, when removed,

interesting details in connexion with the last toilette of the dead.

In the case of the larger body, a, obviously male, which lay eastward

of the other and nearer to the entrance, the face-cover contained in

the middle a piece of figured silk showing a very fine design of

distinctly `Sassanian' style.

Below this cover was a pair of

`spectacles', placed over the eyes, consisting of a thin plate of

silver, formed into two lotus petal-shaped pieces which were joined

end to end. The slightly embossed centre of each is punched with a

number of small holes and the flattened edges drilled for sewing on

to the silk with which the surfaces were covered. The exact objective

intended to be served by these 'spectacles', of which further

examples were recovered on other bodies, still remains to be

ascertained.

However, the most curious and instructive discovery here made was the following. Mashik, our special cemetery assistant, whom long practice in searching the dead had relieved him of all scruples, by breaking the jawbones of the skull recovered from the mouth cavity a thin gold coin which I was able at once to recognize as Byzantine. It has since been identified by Mr. R. B. Whitehead as an approximately contemporaneous imitation of a gold coin of the Emperor Justinian I (A. D. 527-65). This at once supplied a terminus a quo for this particular group of tombs.- It must further be borne in mind that as China had never had a gold or silver coinage, those who at Turfân wished to provide their dead with an adequate obolus for the journey to the world beyond would necessarily have to use a coin of Western origin for their pious purpose, if they wished it to be of precious metal.

Sassanian

Buddhist Protectors – which Stein calls “Monsters”

Thrown on one side lay the clay figure of a monster, with a grinning human head and the body like that of a panther, sitting on its haunches and wearing a three-cornered hat. The grotesque head was well modelled, the colouring of the whole crude. The body was painted pink in front and blue at the back, both sides being covered with bright red spots. A bushy blue tail and four wing feathers found broken added to the grotesque look of the monster. Like two other monsters found in the same part of the cemetery this demon was probably meant to keep off evil spirits from the abode of the dead, like the Tu-kuei figures found in Tang tombs of China.

|

|

|

|

Pieces of fabric from Tang gaves (Mid 7th cent) with Sassanian motives

|

|

|

|

Grave deposits of clay and wood from the late 7th century

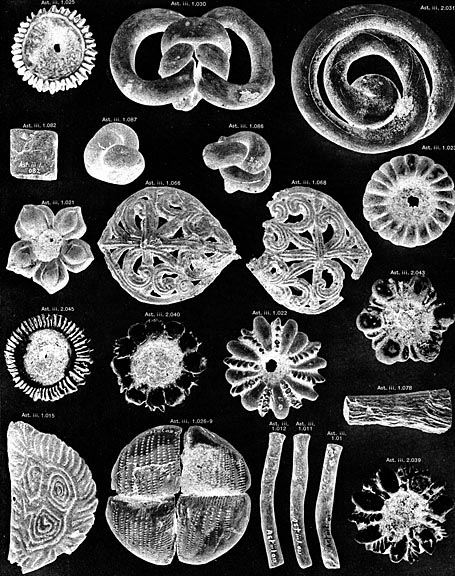

Pl.

XCII, Real baked pastry

The remains of fine pastry recovered here are as remarkable for their

variety of shapes as for their excellent conservation. As PI. XCII

shows, there are represented among them flower-shaped tartlets of

different kinds with neatly made petal borders, some retaining traces

of jam or some similar substance placed in the centre ; bow-knots and

other `twists'; buns, divided cross-wise, `cracknels', and `straws'.

More elaborate productions of the confectioner's art are the thin

ornamented `wafers', and the ogee-shaped open-work cakes, with finely

ribbed sprays of foliage, &c. Some black grapes also were found

here, shrivelled but otherwise in good condition. Considering the

brittleness of all this pastry it seems difficult to believe that it

could have occupied the place where it was found before the coffin

was removed from there.

Innermost

Asia

Anxious as I was personally to assure their security, it was impossible to drag about with me these loads, which, when all the wall-paintings from Bezeklik had been removed and packed, amounted to 145 cases weighing over eight tons(!).

Arrangements had therefore to be made for the dispatch of the antiques to the safe shelter of the Consulate General at Kashgar, and in the first days of February I observed signs calculated to make me hasten these arrangements, as well as the conclusion of my excavations at Astâna.

In the first days of February I observed signs calculated to make me

hasten these arrangements, as well as the conclusion of my

excavations at Astâna. Communications from the well-meaning District

Magistrate of Turfan, politely conveyed yet unmistakable in their

disquieting import, indicated that official inquiries had been made

from head-quarters at Urumchi as to the reasons for my prolonged stay

in the district, the character of my work, &c.

By February 5th

the last big batch of cases containing frescoes had been duly brought

in from Bezeklik. A day later I saw with no small relief the long

string of forty-five laden camels starting for their distant

destination under the care of Ibrahim Beg, the veteran factotum who

had accompanied me on three journeys. Repacked like the rest of my

collection with systematic care at Kâshgar, the contents of all

these cases reached their Indian destination without loss or damage.

The setting up of the Bezeklik frescoes in the building erected for

their accommodation at New Delhi has been progressing ever since

1921.

Innermost

Asia

Korla

Mar 30 –

Apr 6, 1915

After a streneous 45-day march through the uncharted wastes of the Kuruk-Tagh mountains to the northernmost grave sites of the Lopnor, and along the Konche-Darya River from there they reached Korla town on March 30, 1915. -

On April 6th we set out in three separate parties for the long

journey to Kashgar. A variety of reasons, largely connected with my

plans for travels during the summer in the Pamir region and for work

during the winter in far-off Sistân and also with the safe packing

and dispatch of my antiquities to India, made me anxious to reach it

by the close of May.

Lai Singh's task was to keep close to the

Tien-shan and to survey as much of the main range as the early season

and the available time would permit. Muhammad Yäqûb was sent south

across the Konche and Inchike rivers to the Yarkand-darya with

instructions to survey as much as conditions would permit of its main

channel as far as the northern edge of the Yarkand district. Most of

our camels were sent with him under very light loads, in order that

they might benefit by the abundant grazing in the riverine jungles

after all their privations and before the time came when I should

have to dispose of them.

I myself felt obliged, in the interests

of antiquarian research, as well as in view of the great distances to

be covered within the available time—my marches between Korla and

Kashgar aggregated some 938 miles in 55 days—to keep in the main to

the long line of oases which fringes the southern foot of the

Tien-shan.

Innermost

Asia

Kashgar 2

May 31

- July 6, 1915

My arrival at Kashgar on the morning of May 31st had brought me back to my familiar base in time to benefit by all the friendly assistance and official support which Colonel (since Brigadier-General) Sir Percy Sykes, who had temporarily replaced Sir George Macartney as H.B.M.'s Consul-General, could give me before his departure a week later for a shooting trip in the Russian Pamirs.

The most troublesome part of this work and that which took longest time was the careful repacking of my collection of antiques for its long and difficult journey across the Kara-koram to Ladak and thence to Kashmir. The assemblage of the requisite materials and the careful sorting and packing of the antiques, many of them of an extremely brittle and friable character, kept my assistants and myself busy for fully five weeks. It was due mainly to the care then taken that the fragile contents of those 182 tin-lined cases, after a difficult journey of over 800 miles through high mountain ranges and across ice-covered passes on camels, yaks and ponies, finally reached Kashmir safely.

Amid the mass of work which kept me fully occupied all through that

hot month of June, none caused me more concern than the arrangements

for my long-planned journey across the Russian Pamirs and through the

mountains and valleys north of the Oxus.

I had conveyed the

request that I might be enabled, with the permission of the Imperial

Russian Government, to make my way from Kashgar towards the

Trans-Caspian railway and thus to northeastern Persia and Sistan by

the route which the ancient silk trade may be assumed to have

followed across the Alai and along the Kara-tegin valley.

On the 6th of July I at last found it possible to leave Kashgar,

after completing all arrangements for the safe passage of the eighty

heavy camel-loads of antiques to India. But the summer floods in the

Kun-lun valleys, due to the melting glaciers, would not as yet allow

of the departure of this valuable convoy towards the Kara-koram

passes.

Innermost

Asia

Through the Russian Pamirs to

Samarkand

Jul 6 – Oct 22, 1915

Lake Victoria – Kara-Kul

August

27, 1915

Karakul

Lake from its eastern shore

Ever since my youth I had longed to see the truly 'Great' Pamir and its fine lake, of which Captain John Wood, its modern discoverer in 1838, had given so graphic a description. This desire was greatly increased when the closer knowledge since gained of the topography of the Pamir region had confirmed my belief that the memories of those great old travellers, Hsian-tsang and Marco Polo, were associated with the route leading past the lake. The day of halt, August 27, spent by the sunny lake shore was most enjoyable.

Bartangh River

Sep

28, 1915

Down

the Bartangh River in a coracle

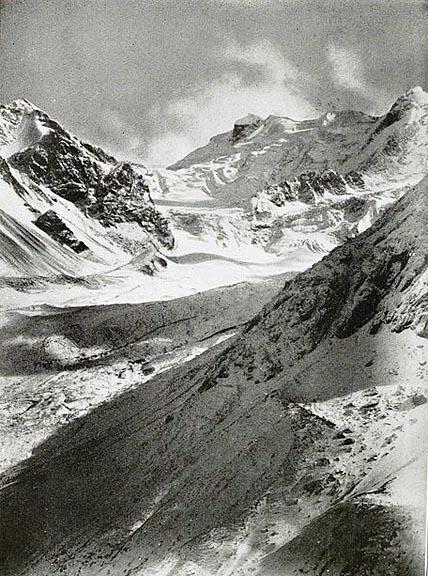

Across the Shitam Pass into the

Roshan

Sep 21, 1915

Shitam

Pass, 5282m

For progress to Roshan, the mountain tract adjoining Shughnan on the north, it would have been easier to descend the Ghund valley to the Oxus below Khoruk and then from Kala-Bar-Panja on the opposite side to have followed the right bank of the river by the newly made Russian bridle-path down to Kala-i-Wamar, the chief place of Roshan. But I was anxious to see something of the high snowy range, dividing Shughnan from Roshan and the drainage of the Bartang river, which I had first reached more than a month before at Saunab. So I preferred to make my way to Roshan by the high pass which leads across the range from above the small village of Shitam. Light as our baggage was, it proved impossible to take it on laden ponies beyond a point about 12,600 feet above sea-level.

On the ascent made next day with load-carrying men, it was necessary

alternately to advance over a much-crevassed glacier and to climb

steep rock couloirs before, after six miles of such trying progress,

the narrow arête of rock forming the pass was reached at an

elevation of some 16,100 feet. The magnificent views opening from

this height were a fit reward for our toil.

Innermost

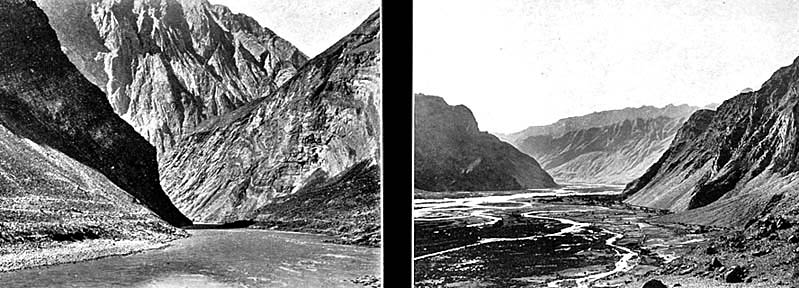

Along the Upper Oxus Valley to

Samarkand

Oct 14 - 20, 1915

The

Oxus Gorge and its upper Valley

Starting on October 14th from Ab-i-garm I left behind the last of the valleys which descend from the Pamir region, and also the westernmost portion of that ground within the drainage area of the Oxus with which I could hope to gain some closer acquaintance on this journey. Regard for the time needed to reach my next goal in distant Sistan and for the work planned there before my return to India obliged me to seek the Trans-Caspian railway at Samarkand by the nearest route and as quickly as possible. The nine rapid marches, covering some 270 miles, which brought me there across comparatively well-known parts of the Bokhara hills offered little chance for close observation.

After crossing another fine plateau, that of Kinnak, which nomadic Özbegs, known as Kongrad, from the tracts north of the Oxus frequent for its grazing, we reached the town of Shahr-i-sabz, in the wide and abundantly irrigated valley draining towards Karshi, on October 20.

Samarkand

Oct 22,

1915

Thence on the following day a long and dusty drive carried me across the Takhta-karacha pass and the wide peneplain overlooking the Zarafshàn valley to Samarkand.

The extensive repairs that our baggage and kit needed after three months of rough travel in the mountains, together with other work, detained me for two days in this great busy city. Its Russian part appeared to have grown greatly since my first visit in 190I and looked even more than before like a town of Eastern Europe. Having previously visited the noble monuments of Timûr's period, I employed my present stay to inspect the plateau of Afràsiab, covered with debris mounds, to the east of the present city. It marks the site of the ancient capital of Sogdiana, the K`ang-chii or Sa-mo-chien of the Chinese records and the Maracanda of Alexander's historians. --

From Samarkand Stein went by train to Ashkhabat and from there,

skirting the border of (closed) Afghanistan, to Mount Kwaja and the

province of Sistan, Iran to perform further archeological

investigations in Southeastern Iran.

Innermost

Asia

Nasratabad, Sistan

Dec 1-6, 1915

Our march of November 30, which brought us over a

vast fan of detritus and gravel down to the shore of the Hamun, the

great terminal basin of the Helmand, was of a kind to bring back

vivid memories of a familiar desert region of innermost Asia. For the

ground over which we travelled here for more than 32 miles was just

like that over which the approach lies to the shores of Lake Hamun. A

day's march from the Hamun to Nasratabad. There I was most kindly

received by Major (since Lieutenant-Colonel) F. B. Prideaux, H.B.M.'s

Consul for Sistan and Kahn.

Innermost

Asia

Mount Koh-i-Khwaja and the Fort of

Ghâla-kôh

Dec 6, 1915-Feb 18, 1916

Koh-i-Khwaja,

View from the Ghâla-kôh Fort.

The top of Ghâla-kôh commands distant vistas over the isolated peaks and ridges into which the Ghâla-kôh range skirting from NW. to SE. is broken up at this end, and over the much-eroded slopes where side spurs have `matured' into bare hummocky peneplains. A veil of dust haze, like that which I had seen so often lying over similar landscapes at the foot of the K'un-lun or the range above Kashgar and Yarkand, hid the plains of ancient Drangiana far away to the east.

|

|

|

On December 6th I left the hospitable roof of the British Consulate

at Nasratâbad for Kôh-i-Khwaja, and passing next morning beyond the

village of Daudi over flat uncultivated ground liable to inundation,

arrived at the edge of Lake Hamun where it faces the rock island of

Kôh-i-Khwaja. My reason for visiting the ruined site to be found

there first was that this conspicuous hill, rising in complete

isolation more than 400 feet above the central portion of the Hamun

marshes and the level expanse of the Helmand delta, bears on its top

much-frequented Muhammadan shrines which form the object of regular

pilgrimages. Its sanctity is marked by its very name, the `hill of

the Saint', i. e. `Ali.' The very striking natural features of this

hill, rising as it does in the very center of a wide lacustrine

basin, were certain to have attracted local worship from early times,

and belief in the tenacity of such worship suggested a great

antiquity of the ruins.

Innermost

Asia

The citadel complex was first investigated by Marc Aurel Stein in

1915-1916. The site was later excavated by Ernst Herzfeld, and was

again investigated by Giorgio Gullini in a short expedition of 1960.

Initially, Herzfeld tentatively dated the palace complex to the 1st

century CE, that is, to the Arsacid period (248 BCE-224 CE). Herzfeld

later revised his estimate to a later date and today the Sassanid

period (224-651 CE) is usually considered to be more likely. Three

bas-reliefs on the outer walls that depict riders and horses are

attributed to this later period. Beyond the citadel at the top of the

plateau are several other unrelated buildings, of uncertain function

and probably dating to the Islamic period.

Wikipedia

By train from Nushki to

Srinagar

Feb 21 – Mid March, 1916

On February 21, 1916 I reached Nushki, whence the railway carried me first to Quetta and subsequently to Sibi, the cold weather head-quarters of Sir John Ramsay, then Governor-General's Agent and Chief Commissioner, of British Balûchistân.

Finally, after the middle of March, I reached Kashmir, which had been

the base for all my Central-Asian expeditions and from which I had

started close on two years eight months before. There at Srinagar the

182 cases of my collection of antiquities from Chinese territory had

safely arrived by the previous October.

Innermost

Asia