|

|

|

|

Sir Aurel Stein's Second Expedition

1906-1908

On Google Earth

To

open this map you have to download

GE onto your hard-disc

Stein's Large Map of Turkestan (2.2 Mby)

Collection of Stein's expedition maps as Google-Earth overlays (inaccurate but still very useful!)

Stein's Second Expedition

During 30 months of fieldwork, Stein travelled over 16,000 kilometres. In April 1906 he crossed the Indian border, and passed through Swat, Dir, Chitral and Mastuj [all today in Pakistan], collecting historical and ethnographical data. While descending on the glacier of the 4,700 metres high Darkot Pass, he tried to trace the path of a military expedition, described in the Tang Liudian (Encyclopaedia of administrative law of the six divisions of the Tang bureaucracy), that crossed the Pamir and the Hindukush and descended towards Gilgit under the leadership of Gao Xianzhi (d. 756) in 747. Stein obtained the permission of the Afghan king to cross Wakhan and the Afghan Pamir, before taking a rest in Kashgar.

He then travelled through Yarkand to Khotan, spending the summer months in the unmapped highlands of the Kunlun range. Following this he excavated unknown settlements around Khotan, before returning to Niya. From Niya he went through Charchan to Charklik, and finally visited the ruins of Loulan.

In January 1907 he began to excavate the ruins of Miran. In February he continued his journey towards the caves of Dunhuang. At the final reach of the Suloho, he discovered some parts of an ancient wall that he called limes (border defenses).

Over the course of two months he surveyed a length of about 220 kilometres, and found the so-called Yumenguan (Jade Gate). The wall was built in the Han period to prevent the Huns in the north from invading.

In May Stein set off for his next destination: the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, where one of the most significant archives of manuscripts was discovered by Wang Yuanlu in 1900. In a sealed cave, thousands of manuscripts dating to between the 5th and 11th centuries, and silk paintings, mainly from the Tang period, were preserved in excellent condition. This discovery gave a new impetus to studies related to medieval China and Central Asia.

In June 1907 Stein travelled towards the oasis of Anxi. He later began his cartographic survey in Nanshan, followed by a second winter excavation season in the Tarim Basin.

Covering a distance of 1,400 kilometres from Anxi to Karashahr, he followed the military and trade routes in use since the Tang dynasty between China and the West. He surveyed important sites in Hami (Kumul) and Turfan

In December he began to investigate the Buddhist sanctuaries of Ming-oi, to the south-west of Karashahr. Having visited Kuchar, he crossed the Taklamakan from north to south, heading in the direction of where the Keriya River meets the desert.

In February 1908 he began new archaeological research in Karadong. He later set off for the source of the Yurungkash River.

While surveying in the Kunlun mountains, he suffered a frostbite in his feet and had to have the toes of his right foot amputated.

In Oct 1908 he had himself carried on a stretcher to Leh and returned from Ladak via Srinagar to London.

The popular description of the second expedition entitled “Ruins of

Desert Cathay” was published in 1912. The scholarly results of the

expedition were published in the five volumes of “Serindia”

(1921).

Text from stein.mtak.hu

Records of Stein's Second Expedition:

Contents

of Serindia Vol 1-5

Popular description of Stein's Second Expedition

Contents

of Ruins of Desert Cathay, Vol 1-2

For faster reading:

Comprehensive 1-vol Description of Stein's travels

"On

Ancient Central Asian Tracks"

Without compunction I have cut suitable sentences from the meticulously verbose texts of Stein's manuscripts and pasted them without quotes or ellipses into my text.

Across the Hindukush to Chinese Turkestan

Srinagar-Swat-Dir-Darkot-Wakhan-Kashgar

2650

km

April

–June 23, 1906

|

|

|

|

Stein had received the royal permission of the King of Afghanistan to cross the Wakhan valley into China. He took a more westernly route than in 1900 through Swat and Dir Valleys to the Baroghil Pass. On his way he explored the historical route of Chinese general Kao Hsien-chih who in 747 A.D. led his force over Darkot Pass for the successful invasion of Yasin and Gilgit. From the Upper Wakhan he proceeded via Tashkurgan and east of Mount Mustangh Ata to Kashgar

Kashgar

June

9-23, 1906

|

|

|

|

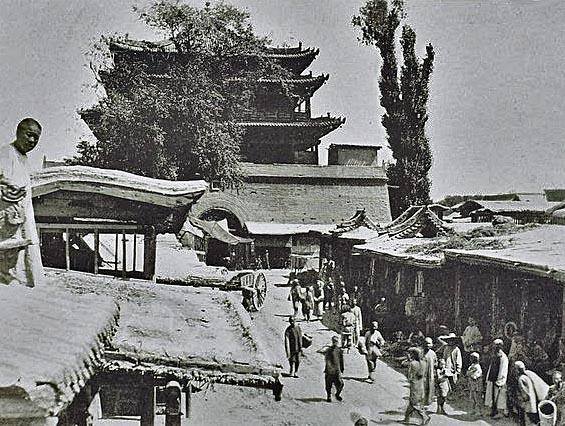

Kashgar, Six Years after

My arrival at Kashgar

meant a return to ground familiar already from prolonged visits in

1900-190I . There my old friend Mr. (now Sir) George Macartney,

K.C.I.E., then the political representative of the Indian Government

and now His Majesty's Consul-General for Chinese Turkestan, offered

me the kindest welcome. But neither this nor the need of some

physical rest after six weeks of constant and arduous travel would

have been a sufficient inducement for a fortnight's stay had not a

host of practical tasks, connected with the organization of my

caravan, the purchase of transport animals, Hassan Akhun to head my

camels, etc., kept me hard at work all that time. Sir George's kind

offices, supported by his great personal influence and to some extent

also by a recollection of my previous archaeological labours about

Khotan, were a great help in securing the goodwill of the provincial

Chinese government for my fresh explorations.

It was a service of quite as great importance, when he recommended to me a qualified Chinese secretary in the person of Mr. Yin Ma Chiang or Chiang Szû-yeh, to give him his familiar title. For the tasks before me the help of a Chinese literatus had appeared from the first indispensable. I have never had a chance of extending my philological equipment by a serious study of Chinese. A kindly Fate gave me in Chiang Szû-yeh not merely an excellent teacher and secretary but a devoted helpmate. Full of true historical sense he took to archaeological work with keen zest and intuitive aptitude, and whether the remains to be explored were Chinese or foreign in origin, he watched and recorded everything with the same unfailing care and thoroughness. Apart from the great personal benefits which I derived throughout my explorations from the companionship of this learned Chinese comrade, science owes Chiang Szû-yeh direct debts for valuable scholarly labour in connexion with numerous tasks I shall have occasion to mention hereafter.

Early in the afternoon on June 23rd, I took leave of my kind hosts and the friendly shelter of Chini-bagh to start for Yarkand, my first étape on the long journey south-eastwards. It was not without a feeling of regret that I cast a farewell look over the sun-lit terraces of the garden and the stately poplar avenues which give shade to its walks.

The Macartneys by their hospitality and unceasing care had made my

stay a time of real rest in spite of all hurried labours. On saying

good-bye to them I felt as if I were parting with the last living

link, too, which bound me to dear friends left behind years before in

distant Europe.

Ruins

of Desert Cathay

Yarkand and Karghalik

June

26-July 7, 1906

After the trying heat of that afternoon and evening spent on the first march between Kashgar and Yapchan I realized that my travelling would have to be done mainly at night, both for the men's sake and for that of the animals. To take shelter during the day in a small tent such as mine was out of the question. So I had to abandon the thought of camping in the gardens which had offered peaceful retreats on former journeys, and instead to look out for a more solid roof to rest under during the heat of the day.

There were the official Chinese rest-houses or 'Kung-kuans' to receive me, spacious enough to accommodate us all. But their state of cleanliness left much to be desired. I preferred to seek refuge in the houses of well-to-do villagers. Again I was struck by the degree of comfort to be found there, far higher than anything in corresponding conditions in India.

It was just the season to make me realize fully the advantages of the Aiwan, that prominent pavilion in well-to-do people's houses throughout the southern oases. It is a kind of square central hall or Atrium, having a roof well raised over the central area and provided with clerestory openings on all four sides. Sometimes on one or two sides the upper wall portion shows merely a grated wooden framework, freely admitting light and air. Thus during the hot summer months the Aiwan gives not only cool shade but access for any fresh breeze. Rooms or

passages opening from this Atrium communicate with the rest of the house. One or two rooms, close to the entrance from the outer court, form the usual guest quarters known as ' Mihman-khanas.' Gay cotton prints hung as dados round the walls and Khotan carpets spread on the floors make them look quite cosy. But as light and air are admitted only by a small opening in the mud roof, the Aiwan itself makes far more inviting summer quarters. Raised platforms extend along all its walls, broad enough for rest or for work, and, as the position can be varied, what sunshine and heat passes in may be dodged.

The refreshing cool air of my quarters made it easy to use my four days' stay at Yarkand to the full. Additional ponies were secured after a good deal of trial and bargaining, among them a good-looking young bay horse for my own use, which passed as of Badakhshi blood. It proved with experience as hardy a mount as I could wish for, indefatigable on the roughest ground and quite inured to the privations of deserts without grazing. So, in spite of its unsociable temper 'Badakhshi' in time became dear to my heart as a constant companion.

Two long marches on July 5th and 6th brought me to Karghalik. The

barren yellow sands of the desert edge remained ever in view as we

moved south

Ruins

of Desert Cathay

Curious

bazaarliks watching Stein's caravan in Karghalik

Along the Foothills of the Kunlun

to Khotan

July 7

- Aug 5, 1906

Excursions into the cool Kulun Mountains

The

desert had become too hot (105 F) even at night. Stein decided to go

on a detour of the Kunlun range. At its elevations above 3000 m it

would be cooler. He sent his Indian surveyors ahead and followed with

a much reduced caravan.

After an intial exploration searching for a passable entry south of Khargalik he made his way to Khotan, Finding Khotan still unbearabely hot he set out a second time towards Nissa (mid July). Both routes appear entangled on the low resolution facsimile map.

The problem with Steins geographical surveys is - he would spend the next summer in the Nanhshan and the summer of 1908 on a third exploration of the uncharted Kunlun - that his local names are not traceable on modern maps, neither do his maps agree with the satellite maps of today. My alignement of these routes is, therefore, only tentative and highly approximate.

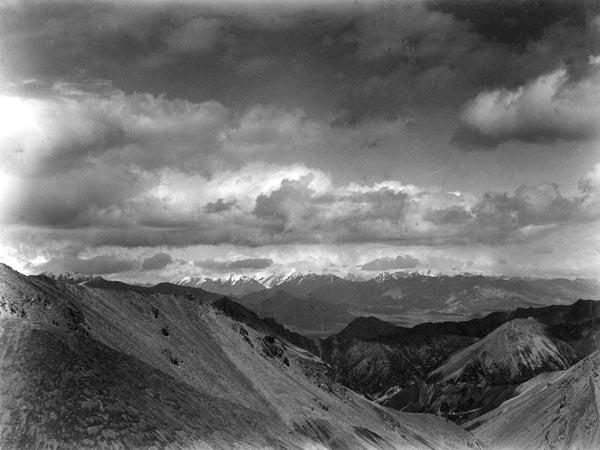

The

Kunlun Range from the Desert south of Karghalik

In the early dawn of July 7th I started from Karghalik southwards. There was just light enough as we rode through the Bazars to observe the gaily decorated cook-shops and a stately Mosque and Madrasah with polychrome woodwork. Karghalik once again reminded me of some small town in Kashmir, probably on account of its fine trees, the abundance of running water, and the plentiful use of timber in its houses

Slowly our animals dragged themselves over the curious stretch of red loess which extends for over a mile beyond. When the rising dunes told me that we were getting near to ` My Lord of the Sands' Shrine,' which was to give us shelter for the night's halt, animals and men worn out by a march of some thirty-six miles over such ground. I recognized the high poles and modest huts of the `Pigeons' Shrine ' amidst patches of reeds and tamarisk, growing between the dunes.

The sacred birds which now receive the wayfarers' worship, instead of the sacred rats of Buddhist days, had retired to rest when we reached the spot by nightfall. So there was nothing to disturb the delicious peace of the desert. It took nearly two hours more before the last of the baggage ponies had come in.

When I rose next morning at 4 A.M., later than usual in those days,

the air was still fresh, the thermometer showing 6o° Fahr. While the

baggage was getting ready I made my food offering to the sacred

pigeons, a duty which my old followers would on no account have

allowed me to neglect, to secure the holy birds' goodwill for the

long journey before us.

Desert

Cathay

Khotan

Aug 5 -

Sep 15, 1906

A month later, on August 5 Stein was approaching Khotan from the south. Here follows his unusually emotional account of his “home-coming” to Khotan, well remembered from his first expedition.

T'ang

Ta-Jên, the Military Amban of Khotan, with his Sons and Attendants

A Nostalgic Home-coming.

The day which brought

me back to ' the Kingdom of Khotan ' will long live in my memory as

one of the happiest of my many journeys. It is always delightful to

revisit scenes to which one's thoughts have longingly returned for

years past, and still more delightful to find that the memory of

one's self still lives among those scenes.

I was met by quite a cavalcade of Begs sent from the Amban's Ya-mên. At Zawa I found the neat little official rest-house by the road-side gaily decked with red cloth, and refreshing tea and fruit ready on the raised central platform of the courtyard. Fresh evidence, too, of the Amban's attention came in the form of pony-loads of fodder for my animals and provisions for myself, offered as a special sign of regard at my entrance into the district. The Kara-kash River, now swollen by the melting snows, could not be crossed on the high road that leads straight to Khotan town. Boats were to be found only at Kara-kash town, some ten miles farther down.

As I approached Kara-kash, my escort was joined by the local Beg, a person of consequence, looking grand in his blue silk coat and official Chinese cap with crystal button and horse-tail. As etiquette makes all such dignitaries insist on riding in front of one, in due order of rank, there was plenty of dust to be swallowed in return for such exalted attention.

A march of some sixteen miles on August 5th brought me back once more to the Khotan capital. It was a day of trying heat, but full of most cheering impressions. The crossing of the Kara-kash river, now in full flood, took us a long time ; for though there were two fairly big ferry-boats available for our party and baggage, the rapidity of the current and the sand-banks, sorely tried the modest skill of the 'Suchis' or watermen.

At the reception-hall built by the road-side I found a pompous gathering of Chinese officers in flowing silk robes, and an array of picturesque figures with swords and halberds representing a selection from the garrison. The military Amban, T'ang Ta-Jên, who, a descendant of the imperial Chinese line, did the honours and received me with a great show of friendly animation,

Badruddin Khan, the head of the Afghan traders' community, had

prepared quarters for me at Niaz Hakim Beg's old garden palace,

Nar-bagh, where in 1901 my last stay in Khotan had been spent. It was

only when I passed through its shady Aiwans and halls into the

familiar garden with its central pavilion, where I again established

myself, that I felt fully assured my longed-for return was a

reality.

Desert

Cathay

Keriya

Oct 7- 17,

1906

Buying Camels

Keriya was the last place where

I could make sure of replacing the camels which, by a succession of

deaths due to some unexplained illness, I had lost since August. We

had taken all possible care of the fine-looking animals acquired at

Kashgar, and used every chance for giving them rest and plentiful

grazing.

For two days I was treated to the wearisome inspection of long strings of camels either too young or past work, while it was evident that more serviceable animals were being carefully kept out of sight. Repeated complaints in the Ya-mên prevailed in the end, and by the fifth day seven big and strong animals had been picked out in spite of all dilatory tactics. - To judge camels' points requires the experience of a lifetime, or rather the inherited knowledge of a born camel-man. So it was no small comfort to feel that in a matter of this sort I could rely on Hassan Akhun's honesty quite as much as on the effect produced among the wily owners by his sharp tongue.

My brave camels from Keriya never caused me worry. They held out

splendidly against all privations and hardships, and after nearly two

years' travel were so fit and fine-looking that, when at last I had

to dispose of them before my return to India, they realized over

seventy per cent profit, of course, for the Government of

India.

Desert

Cathay

Niya and its Ruins

Oct

16 -28, 1906

New Finds in Niya

Niya had, in 1901, been Stein's great discovery, there he had found the first large cachet of Karoshthi tablets. In the interim the treasure hunters of Keriya, instead of searching for gold, had realized that the crazy foreigner would pay well for otherwise worthless written documents. -

Ibrahim,

the Treasure Hunter of Niya

From Ibrahim, " the miller," my old guide, who had first come upon inscribed tablets there, I learned that he had had traced a large group of `old houses' hidden away among sand-hills some miles beyond the western edge of the area previously surveyed. Guided by this information, I decided to take with me as large a band of labourers as my available iron tanks and goat-skins would allow me to keep supplied with water, and to push on excavations rapidly.

On the morning of October 20th we left behind the last abode of the living, and also the present end of the Niya River. Five camels carried the first supply of water for my column, counting in all over fifty labourers.

Partly

excavated house on the new northern site

Marching on over absolutely bare dunes for another two miles, I passed one after another of the ancient houses Ibrahim had reported. They lay in a line along what must have been the extreme north-western extension of a canal once fed by the Niya River. The line proved to be situated only about two miles to the west and north-west of the northernmost ruin we had been able to trace in 1901. But the swelling ridges of sand intervening had then kept them from view.

...Stein's excitement is rising....

I lost no time in commencing my day's work at the farthest ruined structure we could trace. It was a comparatively small dwelling covered only by three to four feet of sand. I had the satisfaction of seeing in each of the three living-rooms of the house specimen after specimen of this ancient record in Indian language and script emerge from where the last dweller, probably a petty official, about the middle of the third century A.D., had left behind this `waste paper.'

The men soon learned to scrape the sand near the floor in the approved fashion and, content with announcing their finds, to leave the careful removal of them to me. I could not help feeling emotion, when I convinced myself on cleaning them from the fine sand adhering, that a number of the rectangular and wedge-shaped letter tablets still retained intact their original string fastenings, and a few even their seal impressions in clay. How delighted I was to discover on them representations of Eros and a figure probably meant for Hermes, left by the impact of classical intaglios ! To be greeted once more at these desolate ruins in the desert by tangible links with the art of Greece and Rome seemed to efface all distance in time and space.

Equally familiar to me were the household implements which this ruin yielded. Remains of a wooden chair decorated with elaborate carvings in Graeco-Buddhist style, weaving instruments, a boot-last, a large eating tray, a mouse-trap, etc., were all objects I could recognize at the first glance,

Niya,

house with sculpted lintel after excavation, 1906

Discovery of the

Hidden Archive of

Honourable Cojhbo Sojaka

October

24th, 1906

For my new camp I had chosen the group of ruins on the extreme west edge of the site which on my previous visit had been discovered too late for systematic exploration. From a small and almost completely eroded structure to the south of the group nearly three dozen official letters on wood were recovered during the early morning of October 24th, 1906.

Here a rich haul awaited me such as I had scarcely ventured to hope for. Already when clearing the rooms north of the large central hall I had come upon some fine pieces of wood-carving (Fig. 92), including an 1 architrave in excellent Gandhara style, which proved that the dwelling must have been that of a well-to-do person.

|

|

|

|

The first strokes of the Ketman laid bare regular files of documents on wood near the floor of a room adjoining the central hall. Most of them were `wedges,' such as were used for the conveyance of executive orders ; others, on oblong tablets were accounts, lists, and miscellaneous office papers,' to use an anachronism. Evidently we had hit upon files from an official's ' Daftar ' thrown down here, and excellently preserved under the cover of sand which even now lay five to six feet deep. In rapid succession over threescore documents of these kinds were recovered here within a few square feet.

Soon we saw that the space towards the wall and below the foundation beam of the latter was full of closely packed layers of similar documents. It was clear that we had struck a hidden archive, and my excitement at this novel experience was great ; for, apart from the interest of the documents themselves and their splendid preservation, the condition in which they were found was bound to furnish valuable indications. I had to master my impatience in order to have the ground in front opened out so as to permit safe and orderly removal of the tablets, and when this had been done darkness came on long before I could extract the whole of the records which lay exposed below the wall. As one large rectangular double tablet after another passed through my hands and was cleared of the adhering layer of dust, I noted with special satisfaction that with one or two exceptions they all had their elaborate string fastenings unopened and sealed down on the envelope in the regular fashion.

It was not only the state of perfect preservation of these documents but their value as fresh materials for the study of the language and the conditions of the period which delighted me. As long as the clay seal impressed in the centre of the covering tablet, and the string passing under it and holding the under and covering tablets tightly together, remained unbroken, all chance of tampering with the text written on the inner surfaces was precluded.

Late that evening I examined the two letters on wood which alone in the whole series had turned up open. I found that both were private letters addressed in due form to the Honourable Cojhbo Sojaka, `whose sight is dear to gods and men.' That this worthy officer had resided in the house I had already ascertained, from the address invariably borne by the office orders on the wedge-shaped tablets which had come to light in such numbers during the afternoon

I felt like a real ` treasure-seeker ' as I extracted in the growing dusk, and later on by the light of a candle, one wooden document after another. But as the operation required much care in order to save the clay sealings from any risk of damage, I realised that my task could not be finished that night.

I discovered that almost all seals remained as fresh as when first impressed, and that most of them were from intaglios of classical workmanship representing Pallas Promachos, Heracles with club and lion-skin, Zeus, and helmeted busts

So in order to protect the deposit against any attempt at clandestine digging on the part of my men who might be tempted to look in such a hiding-place for objects of more intrinsic value than mere wooden`Khats,' I had the excavation in the floor carefully filled up again. Over the opened space I then placed my little camp table topsy-turvy, and by tying its legs with string to the wall posts and sealing the fastenings, I produced a sort of wire entanglement which the cleverest poacher could not have removed without betraying himself. Honest Ibrahim Beg was made to mount guard over the treasures still left behind for the night. He had to sleep in Sojaka's old office.

The clearing resumed early next morning and brought the total number

of perfectly preserved documents close to three dozen, by far the

largest series of complete records which any of the ruins had

yielded.

Desert

Cathay

Endere and Ruins in its

Vicinity

Nov 1- 15, 1906

Endere Fort had been Stein's easternmost site on his exploratory expedition 1900-1901. From here he had returned

Endere

the Tang Fort from the inside

On the morning of November 1st our camp separated. Ram Singh, the Surveyor, was sent south to Niya and Sorghak with instructions to resume his triangulation along the foot of the great Kun-lun range. I myself with the rest of my party set out for the high sands due east in order to revisit the Endere tract before moving on to Charchan. In 1901 I had explored there the ruins of an ancient fort and Stupa.

A curious acquisition made during my stay at the Niya site supplied a special reason. Sadak, a young cultivator from the Mazar working with my party, had on hearing of my intended move to Endere told me of a `Takhta' he had come upon a year or two at Endere.

I was surprised to find that it was a fairly well preserved tablet of a rectangular Kharoshthi document. The writing clearly proved that it belonged to the same early period as the wooden documents of the Niya site, i.e. the third century A.D. Yet my own finds in the ruined fort of Endere in 1901 had established the fact of this site having been occupied at the beginning of the eighth century A.D. and abandoned to the desert soon after.

.... After searching the desert west of the Endere river for six wearing days and finding only a few primitve houses, pot shards and no sriptures Stein returns to the close proximity of the fort. There, in a former Buddhist temple, he recovers the package of four oblong tablets shown below. An excavation of a house produces a fireplace but nothing more exciting. Disappointed Stein decides to move on towards Charchen.....

|

|

|

On the frosty but brilliantly clear morning of the November 13, 1906

I paid off my Niya labourers, new and old, and saw them set out in

great glee for the four days' tramp to their homes. Two days later,

on November 15th, 1906 we set out for the journey to Charchan, which

we were to cover in six marches, just as old Hsüan-tsang had done.

It was the same silent uninhabited waste he describes between Niya

and Char-chan, with the drift sand of the desert ever close at

hand.

Desert

Cathay

Charchan

Nov 17-

23,1906

The brief halt in Charchen, which was all I could afford, proved a pleasant and refreshing change from the last five weeks' desert journeyings for both men and animals. There was plenty of dry lucerne for the ponies to revel in after all the hard fare on reeds and thorny scrub. The camels, too, found a treat after their own fashion on the foliage of the Jigda trees, withered as it was by the frosts.

The freshly hired camels and the supplies we needed for the journey

to Charklik had been secured in good time along with the men's winter

equipment. There were no antiquarian tasks to retain me, and thus I

could keep to my programme and set the caravan on the move again by

the morning of November 23rd.

Desert

Cathay

Charklik

Dec 4-6,

1906

Early on the morning of December ist I started my caravan for the two final marches to Charklik, a distance of close on fifty miles. Almost the whole of this distance lay over a desolate glacis of gravel, fringed only here and there by patches of scanty tamarisk growth and thorny scrub stretching northward.

The tasks I had to cope with during my short stay at Charklik were bound to be exacting. Within three days I had to raise in the small oasis a contingent of fifty labourers for proposed excavations ; food supplies to last them for five weeks, and my own men for at least a month longer ; and to collect as many camels as I could for the transport, seeing that we should have to carry.

Liao

Tao-lao-ye Magistrate of Charkhlik

Fortunately Liao Ta-lao-ye, the Chinese magistrate of this forlorn district, counting in all between four and five hundred homesteads, proved most attentive and helpful. Liao was a slightly built man of about thirty-five, with pleasant and refined features of a typical Chinese cast. His charge was more of an exile, and an unprofitable one in addition, than that of any Chinese official of his rank I had yet met. So the state reception was simple enough, two Turki villagers, disguised as executioners in long red gabardines, being the chief figurants, besides a Chinese clerical attendant and the Begs escorting me. I was struck very pleasantly by my host's remarkably well-bred , manners and quiet air of authority. With the help of Chiang-ssû-yeh, ever the liveliest causeur on such occasions and a true fountainhead of genealogical knowledge in regard to every Chinese dignitary of the `New Dominions,' I soon discovered that Liao was a younger brother of Liu-chi Ta-jên whom I had met in 1901 as Amban of Yarkand.

The difficulties arising over the selection of suitable men for the Lopnor journey were great. Full of apprehensions themselves, and disheartened by the wailings of their relatives who were lamenting them as already doomed, they tried their best to get off by shamming disease or by other subterfuges. Help opportunely arrived on the second day in the persons of two hardy hunters from Abdal. Old Mullah and Tokhta Akhun, his burly companion, had in 1900-1901 seen service with Hedin around Lop-nor, and I had already from Vash-shahri sent a request ahead for them to be summoned from their homes. The Amban's messenger had fortunately found them at Abdal, and now, after having covered over sixty miles by a hard ride through day and night, they turned up cheerfully to take their places by my side.

Miran, First Visit

Dec

8 - 10, 1906

ON the morning of December 6th, 1906, I set out from Charklik for Miran and the Lop Desert. I was up long before daybreak, but it took four hours' constant urging to tear my big caravan from its flesh-pots.

A special reason for an early visit to Miran was supplied by a fragmentary leaf of paper with Tibetan writing which had been brought to me by Tokhta Akhûn, the Abdal hunter, when he joined me at Charkhlik. He declared that he had found it early in the year, while scraping what he described as the roof of a sand-filled dwelling within a ruined fort at Miran. The `find' looked undoubtedly old, and, in connexion with what Tokhta Akhûn could relate about remains of Bats' at other ruins, it determined me to spare a couple of days for a preliminary survey of the site

But in inverse proportion to the small size and roughness of the half-underground hovels was the richness of the rubbish which seemed to fill them to the roof. From the very start of the digging pieces of paper and wood inscribed in Tibetan cropped up in numbers. The profuse antiquarian haul of that first day, which it took me half the night in my tent to clean, sort, and examine, made it hard to leave behind such a mine, even for a time, without exhausting it.

As I could not afford this before my start northward, I determined in

any case to revisit the site. The vicinity of Abdal, where I proposed

to establish my base, and which would have to serve as the

starting-point for the desert journey to Tun-huang, would make it

easy to shape my plans accordingly

Desert

Cathay

Abdal

Dec 10-11,

1906

Stein decided to make Abdal his base station for the exploration of the Lopnor desert. There was plenty of water and some habitation.

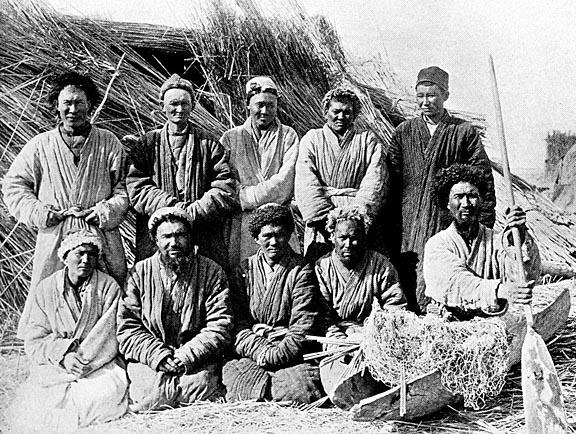

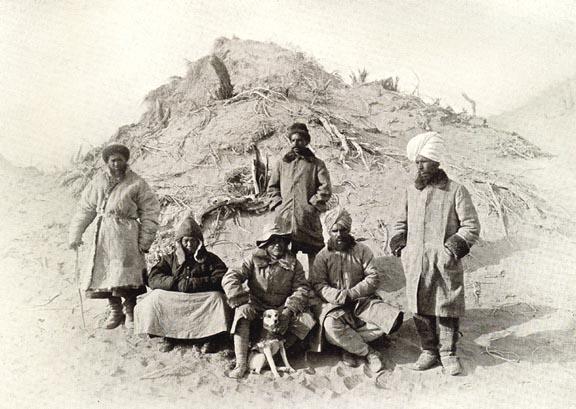

The

Lop fishermen of Abdal

Another nine miles had to be covered to Abdal, a wretched hamlet composed of fishermen's reed huts, and the most notable place for those Lopliks who still cling to their traditional manner of life.

In order to assure a timely start on the morrow I had taken care to

get a ferry constructed well ahead under Mullah's supervision, and to

ferry our camels across the Tarim long before daybreak. It was hard

for me to leave behind at Abdal my devoted helpmate Chiang-ssû-yeh.

But eager as he was to face the `Ta-Gobi,' `the Great Desert,' with

me, I knew well that his feet, unaccustomed to more than short town

walks, would be unequal to the long, trying tramps before us across

dunes and eroded ground.

Desert

Cathay

Towards Lopnor

Dec

11-16, 1906

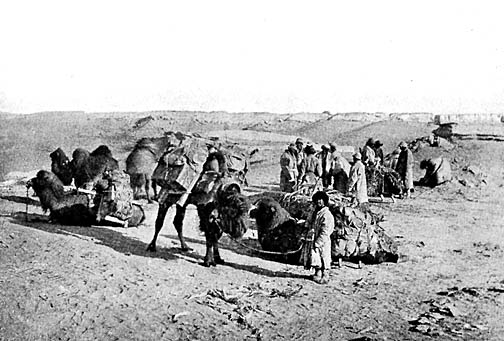

Stein's

caravan entering the Lop Desert

In spite of minimum temperatures of about eighteen degrees of frost at night the last few days had felt warmer than any since leaving Endere, a result no doubt of the much-reduced elevation and the temporary absence of wind. So when, after traversing a monotonous steppe covered with reed beds and occasional tamarisk cones for about eight miles to the north-east, we arrived by dusk at the banks of the lagoon known as Alam-khoja-köl, it was a relief to find that its marshy bed was already hard-frozen.

All the men were set to work cutting ice, and by the light of big bonfires the filling of the huge bags of coarse wool brought for the purpose from Charklik proceeded until midnight.

Next morning I roused the men by 5 A.M. ; but it was four hours later before the fully loaded column could be set in motion. The bags of ice, of which each of the eleven camels set apart for this portion of the transport was to carry three, had been made far too heavy. So all of them had to be opened again, and the surplus weight distributed as well as it might between the remaining camels carrying our supplies and indispensable baggage. In addition, we had some thirty donkeys laden with smaller bags of ice. It was my intention to make them march for two days beyond the last point where drinkable water or ice was available, and leave their ice there for a sort of half-way depot. Of course, the donkeys would need water ; but with a two days' thirst and relieved of loads they could be trusted to return quickly by the track we had come.

As to the camels, they had under Hassan Akhun's supervision been given a thoroughly long drink, six to seven big bucketfuls each, from a hole cut through the ice, and that would have to last them, for all that we knew, for some weeks. Once we had left the last lagoons and salt pools behind us, no fodder of any sort could be hoped for them until they reached the reed beds of the Altmishbulak salt springs, well to the north of Hedin's ruins

On the morning of December 15th, I had all the bags of ice which were available on the thirty donkeys carefully stacked on the north side of the highest sand cone, which we marked with a conspicuous signal staff. I arranged that the donkeys, in charge of two extra men brought for the purpose, should return as quickly as possible to the Chainut-köl base. After two days' rest there the men were to march back to our desert depot with as many donkeys as were needed to bring up the labourers' reserve food supplies, also fresh ice in the bags so far emptied, and some loads of reeds for the camels.

From Hedin's book and the sketch-map of Lop-nor accompanying it I

could also make sure that the route we had so far followed was the

same which had brought him to Abdal. I knew that, in order to reach

the ruined sites first discovered by him, we should now have to

strike a route to the north-north-east which would necessarily lead

near those he had followed in the reverse direction. But there would

be nothing to guide us, only the position of the ruins as indicated

in his route-map and the compass. So I could safely steer my course

by the compass, provided that Hedin's position for the ruins was

approximately correct, without having to fear détours and loss of

time.

Desert

Cathay

Neolithic Finds in the Desert

Dec

15-16, 1906

We had scarcely moved for more than a mile from camp, across eroded ground, when implements of the Stone Age began to appear in numbers. The first which I picked up myself were a rudely worked small axe-head in stone, then an arrow-head and knife-blade in flint. More finds of similar implements, especially of knife-blades, files, and miscellaneous flakes in flint, followed in frequent succession, as the men with me were encouraged to keep a look-out for such small objects. Some of the arrow-heads found that day were so carefully worked that even without expert knowledge I felt certain of their being neolithic.

The day's tramp across those terribly hard clay-banks and trenches, with belts of drift sand intervening, had tired men and animals badly. The heavily laden camels could not do more than about a mile and a half an hour over such ground, nor safely cross it in the dark.

By the light of the fires the men kept blazing, Hassan Akhun was busy at work with his acolytes 're-soling' unfortunate camels whose foot-pads, what with the trials of salt `Shor' and sharp-edged clay-banks, had got badly cracked. I heard the poor beasts still groaning when I went to rest about midnight.

Loulan

Dec 17-29,

1906

I had promised that morning, Dec 17, 1906, a good reward in silver to the man who should first sight a ruin. Impelled by the hope of earning it and the wish to allay their anxiety as to the end of this quest, labourers and all were moving ahead with wholly unwonted alacrity. Great was the excitement therefore when, from the top of a plateau-like Yardang which he had climbed in advance, while his animals were halted and we were setting up the plane-table about a mile from the dry river bed, one of the younger camel-men shouted that he could see a `Pao-t'ai'! All eyes were directed eastwards where he pointed, and soon I verified with my glasses that the tiny knob rising far away above the horizon was really a ruined mound, manifestly of a Stupa. What a relief it was to us all!

The men from Charklik were all buoyed up with sudden animation, and beamed as if they were already arrived at the beginning of the end of their troubles, while my own men affected a look of self-complacent assurance as if things could not possibly have happened otherwise.

The

Stupa at Loulan at last

The distance proved nearly five miles, and though all the men moved on with alacrity, it took us two hours to cover them. On arrival I convinced myself that the large brick mound was that of a Stupa, undoubtedly the same near which Hedin had first camped on his return in 1901.

Sincere was my gratitude, too, to Hedin for his excellent mapping which, in spite of a difference of routes and the total absence of guiding features, had allowed me to strike these forlorn ruins without a day's loss, and exactly where his route map had led me to look for them. I have convinced myself with no small satisfaction that Hedin's position for this site differs from ours only by about one and a half miles in longitude and less than half a mile in latitude, a variance truly trifling on such ground.

Chance would have it that the very first ruin on which I set my men gave cause for encouraging hopes. It was the remnant of a house once manifestly much larger,occupying the top of a small and steeply eroded terrace due south of the Stupa and only some fifty yards off. Four rooms, including one over thirty feet long, could still be clearly made out by the broken walls, built of timber and wattle exactly as at the Niya site. But outside afew slips of Chinese writing, it yielded nothing of antiquarian interest.

Digging

up a trash heap

In none of the ruined dwellings, however, did we strike such a rich mine as in the large rubbish heap extending near the centre of the walled area, and close to the west of the `Ya-mên'. It measured fully a hundred feet across with a width of about fifty. On the south to a height of four to five feet, gradually diminishing northwards, lay a mass of consolidated rubbish consisting of straw and stable refuse. But we had scarcely commenced digging up this unsavoury quarry when Chinese records on wood and paper cropped up in great number, especially from layers two to three feet above the ground level. The careful sifting of all these accumulations of dirt occupied us for nearly a day

By the side of so much evidence of a highly organized civilization, it was strange to come upon a small block of wood which had undoubtedly served for producing fire in the manner current at all periods among savage races.

Along one side it showed four charred holes partially sunk through the thickness of the wood and communicating with the edge by means of flat grooves which were intended to convey the spark to the tinder. Threaded on a strip of white leather, and still attached to the block through a hole was a small peg, having at one end a blunt point which just fitted the holes. It was manifestly this peg which had to be revolved in the holes. But to do this quick enough for the friction to generate fire must have required a drill apparatus, and of this I could find no remains.

However this may have been, it is clear from the fire blocks I

discovered here and at the sites of Niya and Endere, and subsequently

along the ancient frontier wall west of Tun-huang, that this

primitive method of fire production prevailed during the early

centuries of our era all along the line of Chinese advance

westwards.

Desert

Cathay

Christmas Eve 1906

In the afternon of December 24, I suddenly noticed a commotion among the groups of diggers, and shouts of 'Dakchi keldi' ('the Dak-man has come '). I could not believe my ears, but as I looked up, my eyes fell in amazement upon the familiar figure of honest Turdi, wearily trudging towards me with a bag over his shoulder.

At first the sudden apparition of my faithful `Dakchi' from Khotan seemed miraculous. On November 15th I had seen him last setting out from the Endere River with my mail bag, which he had strict orders to deliver personally to Badruddin Khan at Khotan. He had done so twelve days later. Since parting I had marched over 500 miles in the opposite direction almost without a halt—and yet here he was in the midst of this awful Lop Desert to deliver to me Badruddin Khan's devoted Salams and three Kashgar Dak bags tucked away into one !

All work stopped at once, and in the midst of an admiring circle of labourers, grateful like school-boys for an early closing of class, honest Turdi was besieged with questions. Yes, he had trudged it to Khotan and duly seen the Khan Sahib ; slept a night in his house, and been peremptorily sent off next morning with this fresh Dak, but mounted on a hired pony this time, and provided with a good fur coat. Twenty-one days had sufficed for my hardy postman to cover the thirty usual marches reckoned between Khotan and Abdal. There he found that I had left for the desert without instructions for any one how to follow me. With a mind which had more than the usual share of dog-like fidelity—and simplicity, he took this for a reason to push on and join me.

And now that by Allah's grace they had found me and escaped the peril of dying of thirst in this strange desert of clay, said Turdi, would I look at the bags from Kashgar and see that the seals of Macartney Sahib were intact in the little wooden seal-cases attached to the ends of the fastening strings ? For then he could leave them in my hands and take a good sleep by the camp fire.

It was a delightful surprise for my lonely Christmas Eve in the desert to have this big load of letters from distant friends suddenly descending upon me as if it had been brought through the air.

Across the Desert to the Tarim

Dec

29, 1906 – Jan 1907

Various considerations combined to settle the direction of my course. It would have been most tempting to move to the east along the foot of the Kuruk-tagh hills, and thus to trace if possible the ancient trade route which the ruined Chinese station had once guarded, right through to the point where it diverged from the desert track still connecting Charklik with Tun-huang. But I knew well that for a direct distance of at least 120 miles no drinkable water could now be found along the line which that route must have followed.

There was little chance of novel observations westwards, where the old trade route could be followed along the foot of the Kuruk-tagh to the Tarim ; for Hedin had marched by that line on his first visit to the ruins.

Now by striking through the desert to the south-west I should be able to survey wholly unexplored ground. At the same time this route offered the further attraction of taking me straight to the ruined fort of Merdek-shahr, which Hedin had seen in 1896 not far from the eastern lagoons of the Tarim, and which I was anxious to examine before resuming my excavations at Miran.

Loading

the camels at Loulan

The morning of December 29, a bright day and the first fairly calm one, saw our departure from the ancient site. All the Charklik labourers who were returning via Abdal had their accounts for wages and donkey-hire duly settled in silver and Russian gold, with an ample Bakhshish in addition.

New Year 1907

The ease with which we had so far been able to obtain fuel, and the need for keeping the camels lightly laden, had made us overlook the necessity of being prepared for this emergency. I got the men to pick up carefully in bags every scrap of decayed wood débris we could sight. But the total crop thus gathered weighed only a few pounds when dusk began to descend.

The temperature of New Year's night had fallen to a minimum of 13 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. So I felt doubly grateful that the morning of the New Year 1907 dawned upon us not merely in brilliant clearness, but without wind. There was no fire to warm myself by in the morning, and even in the sun the temperature of the day did not rise more than a few degrees above freezing-point. ' The march proved tiring to men and beasts alike ; for at intervals of two to three miles broad Dawans up to sixty feet and more in height had to be surmounted

On the morning of Jamuary 4 at last the dunes got lower and lower, and after nearly seven miles gave way to an inlet-like depression covered with dead Kumush stubble and fringed by big cones with living tamarisks. Here we first noticed the droppings of hares and deer, and the tracks made by them and smaller jungle animals. We followed the depression, manifestly the bed of a recent lagoon with traces of a flood channel cutting through it to the south-west, and after another three miles were attracted by a luxuriant bed of reeds.

While the camels fell to grazing on this with the hunger of some ten foodless days, we ascended a low sand-ridge close by in order to get a look-out.

Suddenly Aga-bergan, the carpenter, recognized a Toghrak grove in which only a year before he had helped to make a Loplik's ` dug-out,' and assured us that the lagoon of Köteklik-köl with its fishermen's station was quite near ! The men shouted with joy, and we all pushed on westwards through the thick scrub and reeds until less than half a mile beyond we stood on the north shore of the hard-frozen winding lake.

Marching westwards for about a mile and a half we crossed successive arms of the lake, all covered with ice so clear that we could see right down to the bottom, six to eight feet deep, and watch the fishes moving. Its thickness was about one foot, as measured at occasional holes which fishermen had cut to insert their nets.

Ruins of Merdek

Jan 5-7, 1907

Camp

near Merdek

Thus on striking the Tarim, or rather the Ilek, we found ourselves fully a march to the south of the Merdek ruin. This made it necessary to recover what we had lost in latitude by marching up the Ilek on January 5th. The night had been perceptibly warmer than any of those passed in the desert ; as we moved along sheltered depressions and under a bright sky, the day's tramp was quite enjoyable.By the side of a dry lagoon I sighted the clay rampart of the small circular fort od Merdek overgrown with reeds (Jan 6). Pitching camp there I devoted the day to a close examination of this modest ruin and soon found evidence of its early origin.

Insignificant as was the ruin itself, its date invested it with a

definite antiquarian and geographical interest ; for its existence at

this place proves that a branch of the Tarim must already in the

early centuries of our era have flowed close to the present line of

the Ilek, and this is a fact that was worth establishing in view of

much-discussed theories about earlier wanderings of the Tarim and its

terminal lake beds.

Desert

Cathay

Return to Charklik

Jan

10-22, 1907

Our march on January l0th was most depressing. The track representing the `high road' to Charklik now turned to the south-west and finally forsook the Tarim. The wearisome succession of marshes which we skirted all day manifestly formed the northernmost edge of the Charchan river delta.

Several of my men had suffered severely under the hardships of our desert work ; Muhammadju in particular had never ceased groaning for some days past, complaining of pains which suggested pleurisy—or a creditable imitation of it. A few days' rest under comfortable shelter might restore the physical endurance of my caravan, and only Charklik could afford that.

There was a another even more compelling reason. Our caravan was caught up by a mounted messenger despatched from the Charklik Ya-mên. The cover which he brought proved to be a telegram from Macartney, sent to Kara-shahr in reply to my letter of November 15th, informing me that the sum of 1500 Taels in Chinese silver, which I had asked him to place at my disposal through the good offices of the Tao-t'ai of Ak-su, was to be available for me, not at Charklik where the local administration was manifestly unable to raise such a sum, but at the treasury of Kara-shahr.

Now Karashar situated on the great high road from Kashgar to Urumchi, lay some three hundred and fifty miles away to the north. The telegram had taken over a fortnight to reach me from there, and while I fully appreciated the saving of time effected by the use of the wire between Kashgar and Kara-shahr, I could not help feeling disappointed on finding from an accompanying Chinese-Turki epistle that the prefect of Kara-shahr, evidently fearing risks about the transmission of the silver, had left it to me to arrange for fetching it. It was practically impossible to achieve this without returning first to Charklik; and as it was important that I should receive my reserve of Chinese silver horse-shoes before setting out through the desert for Tun-huang, I decided to make my way to Miran via Charklik.

So on the morning of January 16th, to the great relief of my myrmidons, I changed our course at right angles and headed for Charklik due south. It was a long and dreary day's march. Finally, we reached in the dark of Jan. 16 Charklik, and after a total march of some twenty-six miles found a hearty welcome and shelter in our old host's house.

My stay at Charklik gave my men the rest which they amply deserved and needed. But I myself found the five days to which, in spite of my efforts, it dragged out, almost too short for all the tasks there were to get through. An early visit to the Ya-mên, where Liao Ta-lao-ye greeted me with the cordiality of an old friend, allowed me to arrange for the rapid progress of Ibrahim Beg, who was to proceed to Kara-shahr and fetch my silver reserve with all possible speed. Using freely all official resources, the journey

to and fro could not be accomplished in less than a month, and it was important that my own start for Tun-huang should not suffer delay on that score.

On the morning of January 22nd I was free at last to start back to

Miran with diggers and supplies all complete, but my caravan slightly

reduced in men and animals.

Desert

Cathay

Miran II

Jan 22 –

Feb 11, 1907

Our marches to Miran lay along the route followed before and were uneventful. We reached it on Jan 23 at night. Dear Chiang-ssû-yeh and a dozen of Lopliks from Abdal gave us a joyful welcome. In obedience to my original order they had camped here patiently for a week in readiness for fresh excavations. It was delightful to be reunited once more to my devoted Chinese helpmate.

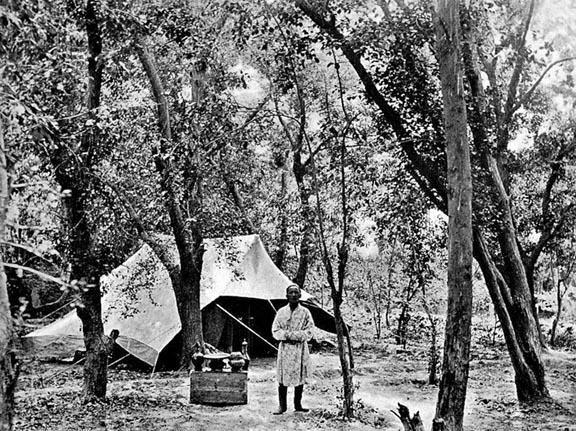

Chiang-ssŭ-yeh's

tent at Miran

Tibetan Documents

It did

not take long to get proof that the ruined fort was likely to fulfil

the promise held out by the previous experimental digging. From a

single small apartment, measuring only some eleven by seven feet, and

still retaining in parts its smoke-begrimed wall-plaster we recovered

over a hundred documents. The rubbish reached in places to a height

of close on nine feet, and right down to the bottom the layers of

refuse yielded in profusion records on paper and wood. With one

remarkable exception to be described farther on they were all in

Tibetan. The total number of documents amounted in the end to more

than a thousand.

Desert

Cathay

Winged “Angels” in a Buddhist Shrine!

Colossal

Stucco Head of a Budda from Shrine M, photo Serindia

On January 29th the advanced state of the fort excavations allowed me to take a portion of my band of diggers across to the ruined temple a little over a mile away to the north-east, where experimental clearing in December had disclosed some sculptural relics of manifestly early type. It was a bitterly cold day. The minimum temperature was 37 degrees below freezing-point ; and in the piercing north wind it seemed as if this would never rise at all. But all the discomforts from cold, wind, and the dust clouds attending work in the trenches were forgotten at times over the interesting results of the digging.

Meanwhile I lost no time in starting work on January 31st at a group of ruined mounds which remained unexplored, about a mile and a quarter west of the fort. The cursory inspection I had made of a cluster of five of them on my first approach to the site, had left the impression that they were much-decayed ruins of Stupas of the usual type.

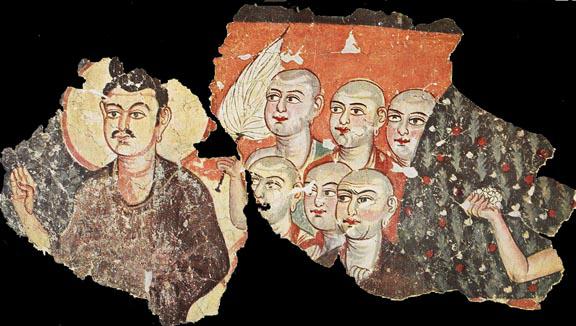

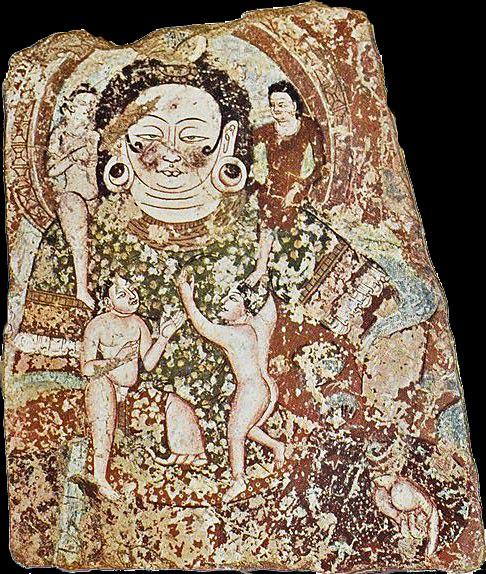

Dado

of Angels from the rotunda of Shrine M, photo Serindia

Iranian

influence in a wall painting from Buddhist Shrine M (3rd cent

AD)

photo Desert

Cathay

The clearing was still proceeding in the afternoon when from the

north and east segments of the circular passage fragments of painted

stucco cropped up rapidly. It was evident that the interior walls of

the cella had once been adorned with frescoes. Yet, when the digging

there had reached a level of about four feet above the floor and a

delicately painted dado of beautiful winged angels began to show on

the wall, I felt completely taken by surprise.

How could I have

expected by the desolate shores of Lop-nor, in the very heart of

innermost Asia, to come upon such classical representations of

Cherubim ! And what had these graceful heads, recalling cherished

scenes of Christian imagery, to do here on the walls of what beyond

all doubt was a Buddhist sanctuary ?

I was still wondering how to

account for the distinctly classical style in the representation of

these Cherubim and the purport of . this apparent loan from early

Christian iconography, when the discovery of a ` Khat,' announced by

a shout from the men, supplied definite palaeographic evidence for

the dating. From the rubble of broken mud-bricks and plaster filling

the passage on the south there emerged in succession three large

pieces of fine coloured silk, evidently belonging to what had once

been a votive flag or stream. [It later turned out that the Karoshthi

text were prayers for the health of a number of persons and their

relatives, all the names given being, significantly enough, of either

Indian or Iranian origin.]

Wall

painting of Hinyana monks with strongly Indian features

Buddhist

Shrine M. Photo Serindia

|

|

|

There still remained the ticklish question how to lift these terribly

brittle panes of mud plaster on to my padded boards without letting

them break into fragments or injuring the delicately painted surface.

A board lightly padded with cotton wool, under large sheets of that

tough Khotan paper, which I never ceased blessing as the best packing

stuff produced in Central Asia, was pressed gently and evenly against

the front surface of the fallen fresco. Next a large sheet of stout

tin, which Ram Singh had managed to improvise out of carefully stored

empty cases and to stiffen with thin iron bands, was slowly

introduced with a sawlike action at the soft back of the broken

panel.

When once firmly held from front and back, the piece of

wall plaster, however large, could be safely tilted forward until,

with its painted surface downwards, it came to lie flat on the padded

board, and could be moved without risk.

Camel

caravan with Miran finds leaving for Kashgar

The odds against these brittle panes of mud plaster travelling safely

to London seemed small. The time for true relief arrived only when,

just three years after that trying exploit at Miran, the cases came

to be opened at the British Museum. Then all doubts about the success

of the hazardous experiment were lifted from my mind. How delighted

my eyes were to behold these fine art relics, probably the most

fragile ever transported over such a distance and over such ground,

brought to safety practically in the same condition as when I had the

good fortune to see them rise from their grave of long centuries in

that dismal wind-swept desert of gravel!

Detailed discussion of

the wall paintings: Desert

Cathay

On the Way

to Tunhuang

Feb 11 - March 2,

1907

Interlude at Abdal

Feb 12

- Feb 21, 1907

A judicious adjustment of pay arrears and rewards to be disbursed at Kashgar gave hope that thr convoy of antiques would be safely delivered. But in spite of continuous driving and pushing it was only on the seventh day from my arrival at Abdal that I saw the caravan, which included also Turdi, the plucky Dak-man, start for their two months' journey to Kashgar.

To get my own caravan ready for the long desert crossing cost simultaneous and quite as great efforts.The provision of a month's supplies for men and animals was a big job, and still more the arrangements for their transport. My united party counted in all thirteen persons, eleven ponies for mounts, and eight camels.

Ponies could not do without fodder, and how to carry enough of this for a month with the rest of the men's food was the crux. To procure camels for the purpose proved impossible. The few Charklik camels which I had secured for the march across the Lop-nor Desert were still too weak from the fatigues undergone to be taken along without imminent risk of a break-down, which would have seriously hampered us when once started on the long desert journey.

In the midst of all this bustle which the resident Lopliks, young and old, seemed to enjoy hugely, there arrived to my relief honest hard-riding Ibrahim Beg with the fifteen hundred Sers of silver in Chinese ' horse-shoes,' for which I had despatched him less than a month before to the Kara-shahr Ya-mên. He had covered the distance there from Charklik, more than 33o miles, within seven days on post-horses, but was obliged to spend fully twice as much time on the return journey owing to the protective company of two Chinese Ya-mên attendants.

Before taking over the quaint horse-shoes,' big and small, I had them, of course, weighed,though I knew that I could trust Ibrahim Beg implicitly in a matter of this sort. The operation was performed with one of those neat and cleverly designed pairs of ivory scales which work on the adjustable lever principle.

When Chiang-ssû-yeh with nimble hands and inexhaustible patience had finished all the weighing, it was found that the number of ounces of silver was short by an amount equivalent to something over 40 rupees. - The explanation was that payment had been made on the official scale of weights accepted at Turkestan treasuries, whereas my own scales were supposed to conform to the weights in use for trade transactions in the `New Dominion.'

It was ten o'clock on February 21 before I could get the whole column, including close on forty donkeys, to move off. The settling of final accounts and claims kept me back for another three hours. But at last I, too, could ride off, after giving much-prized little European presents to the women-folk and children of my host. Chiang-ssûyeh during his long stay in December had made himself a great favourite with the little ones and was visibly affected by the parting.

Following theGreat Wall

Feb

14 - Mar 12, 1907

On his way to Dunhuang Stein discovered the sand-buried remains of

the eastern-most end of the Chinese Great Wall: heavily eroded towers

and gates which defended Chinese Kansu from the Xi-Xia and other

Central Asian tribes. He made the first surveillance of this bulwark,

the antiquarian yield consisted only of a few Tang documents. I omit

this part of his description and refer the reader to the facsimile

edition:

Desert

Cathay

Tunhuang-Dunhuang

March

12 – 24, 1907

modern Pinyin spelling: Dunhuang

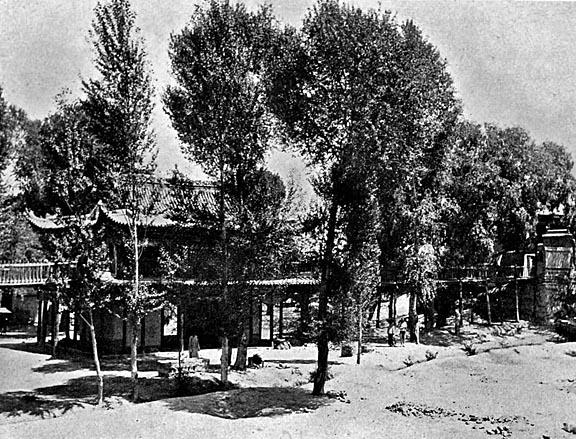

On the morning of March 12th, 1907, we were prepared to make our entry into Tun-huang town. All the men had been looking forward eagerly to our arrival. But circumstances seemed to combine to deprive it of all state and even comfort. An icy gale was blowing from the east, and cutting as it was among the trees and houses, we congratulated ourselves inwardly that we had escaped it in the open desert. But what, somehow, seemed worse was that, though the town was said to be only some twenty Li, or about four or five miles off, no reply whatever was forthcoming to the elegant epistle which Chiang-ssû-yeh, at the very time of our reaching the oasis, had despatched to the Ya-mên, along with that imposing Chinese visiting-card of mine on red paper.

So after some useless wait we set out for the town. Our atlases show it as Sha-chou, `City of Sands' ; but to the local Chinese it is best known by its ancient name of Tun-huang, dating from Han times.

At the magistrate's Ya-mên we met at last a small crowd of idlers, and directed by them, made our way past a couple of picturesque half-decayed temples with fine old wood-carving to the Sarai suggested for our residence. It proved a perfectly impossible place, so filthy and cramped that I decided at once rather to camp in the open.

At last, half a mile or so from its south gate, I discovered a large

orchard with a lonely house at one end which looked as if it had seen

better days. On invading its precincts we found it still occupied,

but luckily by people who were ready to find room for so big a party

as ours.

Cheerfully toddling about on their poor little bound feet

the Chinese ladies huddled as much as they could of their household

goods into one small block of rooms, while we were welcome to make

what use we could of the rest.

At last one of the Turki traders

came to the rescue by changing a few Taels of silver into long

sausage-like strings of copper 'cash ' at a rate which suited his

fancy. Even then it took hours before fuel, fodder, etc.,

arrived.

Desert

Cathay

The “Caves of the Thousand

Budhas”

also known as the “Magao Caves”

First

Visit

March 16, 1907

On the 16th of March I could at last pay my first visit to the famous

cave temples to which my thoughts had turned for so long from afar.

Chiang-ssû-yeh, Naik Ram Singh, and one of Lin Ta-jên's

subordinates were to be my companions.

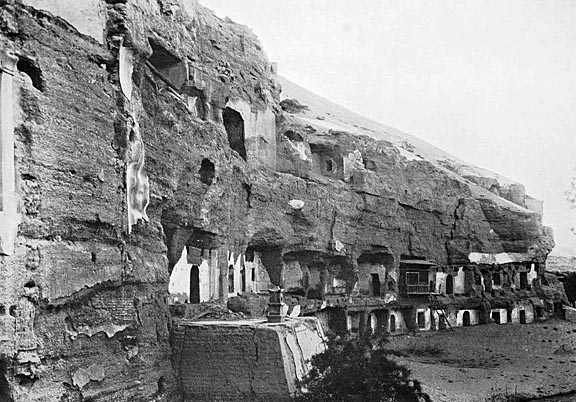

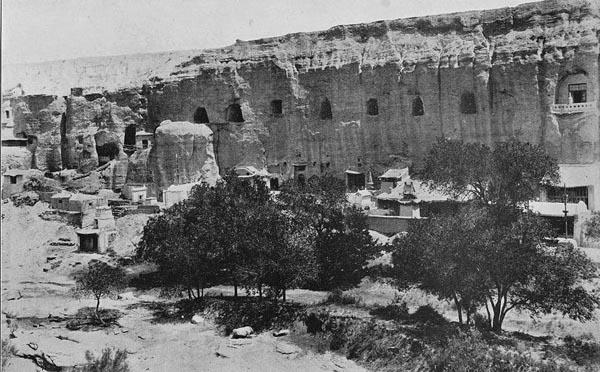

Desert

Cathay

I caught sight of the first grottoes. A multitude of dark cavities, mostly small, was honeycombing the sombre rock faces in irregular tiers from the foot of the cliff, where the stream almost washed them, to the top of the precipice.

Here and there the flights of steps connecting the grottoes still showed on the cliff face. But in front of most the conglomerate mass had crumbled away, and from a distance it looked as if approach to the sanctuaries would be possible only to those willing to be let down by ropes or to bear the trouble and expense of elaborate scaffolding. The whole strangely recalled fancy pictures of troglodyte dwellings of anchorites such as I remembered having seen long, long ago in early Italian paintings.

Dunhuang,

central part of the Caves

At once I noticed that fresco paintings covered the walls of all the grottoes or as much as was visible of them from the entrances. ' The Caves of the Thousand Buddhas' were indeed tenanted, not by Buddhist recluses, however holy, but by images of the Enlightened One himself. All this host of grottoes represented shrines, and I hastened eagerly to take my first glance at their contents. Yet there was no human being about to receive us, no guide to distract one's attention.

In

many caves their front porches had fallen away so that their frescoes

were exposed

All the wall faces were covered with plaster bearing frescoes. Those

on the passage walls ordinarily represented rows of Bodhisattvas

moving in procession or seated in tiers. Within the cellas the

paintings were generally arranged in large, elaborately bordered

panels, either singly or, where the wall surface was extensive, in a

series. In the centre of these there appeared mostly figures of

Buddhas, singly or in groups, surrounded by divine worshippers and

attendants in many varied forms and poses. There were scenes from the

Buddhist heavens, from legends in which Buddhas or saints figured,

representations of life in their places of worship, etc.

Desert

Cathay

As I passed hurriedly from grotto to grotto, faithfully followed by

my literatus, we were at last joined by one of the local priests I

had been looking out for. It was a young ' Ho-shang,' left in charge

of the conglomeration of small houses and chapels which occupied a

place amidst some arbours and fields facing the south end of the

grottoes. He was a quiet, intelligent fellow, quick at grasping what

attracted my interest, and as unobtrusive a cicerone as one could

wish for.

Our guide readily took us to the temple containing a big

Chinese inscription on marble which records pious works executed here

in the T'ang period, and subsequently to the two shrines where

smaller epigraphic relics dating from the Sung and Yuan dynasties are

preserved.

At Tun-huang I had first heard vague rumours about a great hidden deposit of ancient manuscripts which was said to have been discovered accidentally some years earlier in one of the grottoes. And the assertion that some of these manuscripts were not Chinese had naturally made me still keener to ascertain exact details.These treasures were said to have been locked up again in one of the shrines by official order. The absence of the Taoist priest in charge of the manuscripts made it impossible to start operations at once. But the young monk was able to put us on the right track. So I soon let him be taken aside by Chiang Ssû-yeh for private confabulation.

The cache of manuscripts was in a large shrine farther north, bearing

on its walls evidence of recent restoration. The entrance to that

cave had been formerly blocked by fallen rock-débris and drift sand.

After this had been cleared out, and while restorations were slowly

proceeding in its cella and antechapel, the workmen engaged had

noticed a crack in the frescoed wall of the passage between them.

Attracted by this they discovered an opening leading to a recess or

small chamber hollowed out from the rock behind the stuccoed wall to

the right. It proved to be completely filled with manuscript rolls

which were said to be written in Chinese characters, but in a

non-Chinese language. The total quantity was supposed to make up

several cart-loads.

The priest was away in the oasis, apparently

on a begging tour with his acolytes. Chiang Ssû-yeh had thus no

chance to pursue his preliminary enquiries further. But, fortunately,

the young Ho-shang's spiritual guide, a Sramana of Tibetan

extraction, had borrowed one of the manuscripts for the sake of

giving additional lustre to his small private chapel, and our

cicerone was persuaded by Chiang Ssû-yeh to bring us this specimen.

It was a beautifully preserved roll of paper, about a foot high and

perhaps fifteen yards long, which I unfolded with Chiang-ssû-yeh in

front of the original hiding-place. The writing was, indeed, Chinese,

but my learned secretary frankly acknowledged that to him the

characters conveyed no sense whatever.

Desert

Cathay

Opening the Secret Chamber

May 21 - 28, 1907

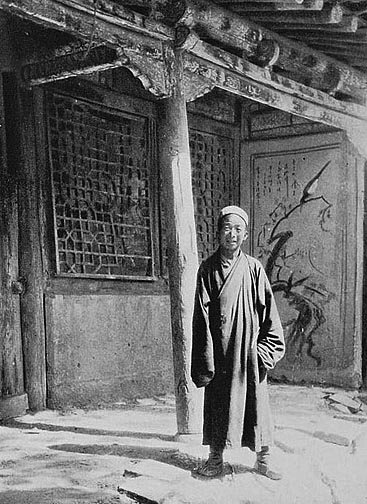

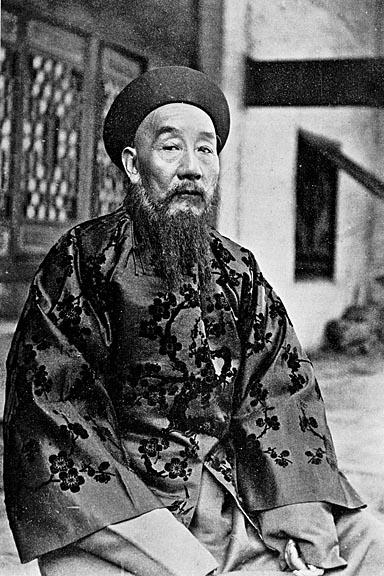

Wang

Tao-shih the priest in charge of the manuscripts

Chiang Ssû-yeh councelled to proceeded slowly, he had induced Wang Tao-shih, the priest, who had come upon the hidden deposit, to await my arrival instead of starting on one of his usual tours in the district to sell blessings and charms, and to collect outstanding temple subscriptions.

Next morning I started what was to be ostensibly the main object of my stay at the site, the survey of the principal grottoes, and the photographing of the more notable frescoes. Purposely I avoided any long interview with the Tao-shih, who had come to offer me welcome at what for the most of the year he might well regard his domain. He looked a very queer person, extremely shy and nervous, with an occasional expression of cunning which was far from encouraging. It was clear from the first that he would be a difficult person to handle.

I thought it best to study his case in personal contact. Accompanied by Chiang Ssû-yeh I proceeded in the afternoon to pay my formal call to the Tao-shih, and asked to be shown over his restored cave-temple. It was the pride and the mainstay of his Tun-huang existence, and my request was fulfilled with alacrity. As he took me through the lofty antechapel with its substantial woodwork, all new and lavishly gilt and painted, and through the high passage or porch giving access and light to the main cella, I could not help glancing to the right where an ugly patch of unplastered brickwork then still masked the door of the hidden chapel.

Meanwhile

I was glad enough to propitiate the young Buddhist priest with an

appropriate offering. I always like to be liberal with those whom I

may hope to secure as `my own ' local priests or `Purohitas ' at

sites of ancient worship. But, unlike the attitude usually taken up

by my Indian Pandit friends on such occasions, when they

could—vicariously—gain `spiritual merit ' for themselves,

Chiang-ssû-yeh in his worldly wisdom advised moderation. A present

too generous might arouse speculations about the possible ulterior

objects. Recognising the soundness of his reasoning, I restricted my

`Dakshina,' or offering, to a piece of hacked silver, equal to about

three rupees or four shillings. The gleam of satisfaction on the

young Ho-shang's face showed that the people of Tun-huang, whatever

else their weaknesses, were not much given to spoiling poor

monks

Desert

Cathay

Late at night a few days later Chiang Ssû-yeh groped his way to my

tent in silent elation with a bundle of Chinese rolls which Wang

Tao-shih had just brought him in secret, carefully hidden under his

flowing black robe, as the first of the promised ` specimens.' The

rolls looked unmistakably old as regards writing and paper, and

probably contained Buddhist canonical texts; but Chiang Ssû-yeh

needed time to make sure of their character. Next morning he turned

up by daybreak, and with a face expressing both triumph and

amazement, reported that these fine rolls of paper contained Chinese

versions of certain `Sutras' from the Buddhist canon which the

colophons declared to have been brought from India and translated by

Hsüan-tsang himself.

Desert

Cathay

Later that day I found the priest evidently still combating his scruples and nervous apprehensions. But under the influence of that quasi-divine hint to Hsüan-tsang he now summoned up courage to open before me the rough door closing the narrow entrance which led from the side of the broad front passage into the rock-carved recess, on a level of about four feet above the floor of the former.

Cave

14 filled with scrolls

The sight of the small room disclosed was one to make my eyes open

wide. Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in

the dim light of the priest's little lamp a solid mass of manuscript

bundles rising in places to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling,

as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area

left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to

stand in. It was manifest that in this 'black hole ' no examination

of the manuscripts would be possible, and also that the digging out

of all its contents would cost a good deal of physical labour.

The

Tao-shih had summoned up courage to fall in with my wishes, on the

solemn condition that nobody besides us three was to get the

slightest inkling of what was being transacted, and that as long as I

kept on Chinese soil the origin of these `finds ' was not to be

revealed to any living being. He himself was afraid of being seen at

night outside his temple precincts. So the Chiang Ssû-yeh, zealous

and energetic as always, took it upon himself to be the sole carrier.

For seven nights more he thus came to my tent, when everybody had

gone to sleep, with the same precautions, his slight figure panting

under loads which grew each time heavier, and ultimately required

carriage by instalments. For hands accustomed only to wield pen and

paper it was a trying task, and never shall I forget the good-natured

ease and cheerful devotion with which it was performed by that most

willing of helpmates.

From

the first I

was

certain that the contents of the hidden chapel must have been

deposited in great confusion around the Xi Xia invasion in 1063 AD,

and that any indications of the

original

position of the bundles at the time of discovery, had been completely

effaced when the recess was cleared out, as the Tao-shih admitted, to

search for valuables.

It was mere chance, too, what bundles the

Tao-shih would hand out to us. Nor was my hurried search the time for

appreciating the import of all that passed through my hands.

It

was from those 'mixed ' bundles chiefly that manuscripts and detached

leaves in Indian script and of the traditional Pothi shape continued

to emerge. By far the most important among such finds was a

remarkably well preserved Sanskrit manuscript on palm leaves, some

seventy in number, and no less than twenty inches long

A

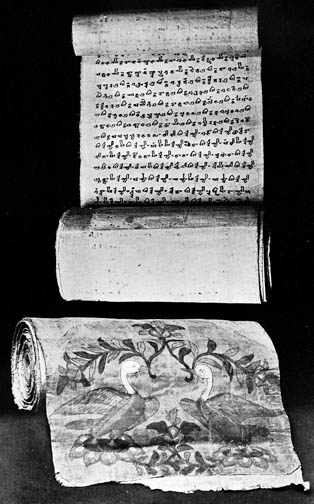

70-foot long scroll in Brahmi script, photo

Among the Brahmi scriptures was a gigantic roll of paper, over 70 feet long, and about one foot wide, entirely covered on its inner side with Brahmi writing in a fair upright hand of what scholars know as the Gupta type. A painting on the top of the outer side showed two cleverly drawn geese standing on lotuses and facing each other. When hastily examining it in part, I could find only invocation prayers in corrupt Sanskrit of a kind familiar to Northern Buddhism.

The

oldest-known block-printed text, an edition of the Diamond Sutra

(dated 864 AD)

Greatly

delighted was I when I found that an excellently preserved roll with

a well-designed block-printed picture as frontispiece, had its text

printed throughout, showing a date of production corresponding to 860

A.D. Here was conclusive evidence that the art of printing books from

wooden blocks was practised long before the conventionally assumed

time of its invention, during the Sung period, and that already in

the ninth century the technical level had been raised practically as

high as the process permitted.

Desert

Cathay

He agreed to let me have fifty well-preserved bundles of Chinese text

rolls and five of Tibetan ones, besides all my previous selections

from the miscellaneous bundles. For all these acquisitions four

horse-shoes of silver, equal to about Rs.5oo, passed into the