Map of manuscripts found in Chinese Turkestan (Xijiang) (source of map)

To enlarge the image click on the map

Sir Aurel Stein's First Expedition

1900-1901

On Google

Earth

To open this map you have to

download

GE onto your hard-disc

Collection of Stein's expedition maps as Google-Earth overlays (inaccurate but still very useful!)

Stein's First Expedition

In the last years of the 19th century, an increasing number of manuscripts, both in known and unknown scripts and languages, as well as other findings, appeared in the region known at that time as Eastern or Chinese Turkestan. They stirred up keen interest among European scholars, but their provenance was entirely unknown, because the local treasure-seekers who offered them for sale concealed their origins.

Map

of manuscripts found in Chinese Turkestan (Xijiang) (source

of map)

To enlarge the image click on the map

Hence Stein decided to carry out systematic archaeological excavations in this territory.

This his first expedition was exploratory with limited funding. Stein had to learn how to raise a caravan of camels and ponies to carry his surveying gear and provisions (food and water!) for a varying number of diggers and camel drivers through a hostile, largely uncharted desert environment: thousands of kilometers on foot. Guided by Hsüen-tzang's (Xuanzang), Marco Polo's, and Sven Hedin's descriptions he was able to discover and record a number of sites of great antiquarian and ethnographic importance among them scores of manuscripts in a variety of scripts and languages.

From 1900 to 1901, he conducted

research around Khotan.

This first fieldwork was already characterized by the

comprehensiveness of all his subsequent expeditions. Alongside

archaeological research, Stein also paid attention to the geography,

anthropology, ethnography and linguistics of the region

His

first expedition (1900-01) was funded by the Government of India and

the Government of Punjab and Bengal, and it was agreed that the finds

should be studied in London and allocated to specific museums later.

He started from his base in Kashmir in May 1900, Stein travelled

across Gilgit

to the Hindukush chiefship of Hunza.

By the end of June, after crossing the Kilik Pass, Stein arrived in

Chinese territory at the head of the Taghdumbash Pamir.

Descending

eastwards to Tashkurghan,

it became possible to figure out the ancient topography of Sarikol by

identifying the localities which the great Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang

had mentioned when passing there in 649 C.E. Stein later referred to

Xuanzang as his “patron saint”, because on his expeditions in

Chinese Central Asia, he followed in the footsteps of this 7th

century Buddhist monk who travelled from Central Asia to India,

returning later to China with Buddhist sutras.

In Ilchi, the

capital of the Khotan district, Stein had evidence of the practice of

forging old books, and possibly other antiques. He then travelled

into the desert, later surveying and mapping the Kunlun range. He

visited ancient sites of Yotkan, Dandan-Uiliq, Niya, Rawak and

Endere.

In May 1901 his journey, undertaken on horseback and by

foot, covering 3,000 miles, came to its end at Osh,

Ferghana, and he returned to Europe across Russia.

Stein

published a popular account of the first expedition entitled

“Sand-buried

Ruins of Khotan” (1903), and a detailed archaeological report

Ancient

Khotan after his second expediton (2 volumes, 1907):

From

stein.mtak.hu

Stein's expedition reports are too voluminous to reproduce in this limited format. I have resorted to a picture album approach accompanied by extensive, detailed maps, enlivened by excerpts and supported by copious references to his original texts, which fortunately exist in facsimily editions by Toyobunko

All Photos are copies of original Stein's photos from the facsimile reprints of Stein's Expedition Reports at NII-Toyobunko, Japan

A Sentimental Leave-Taking from

Srinagar-Gulmarg

May 1900

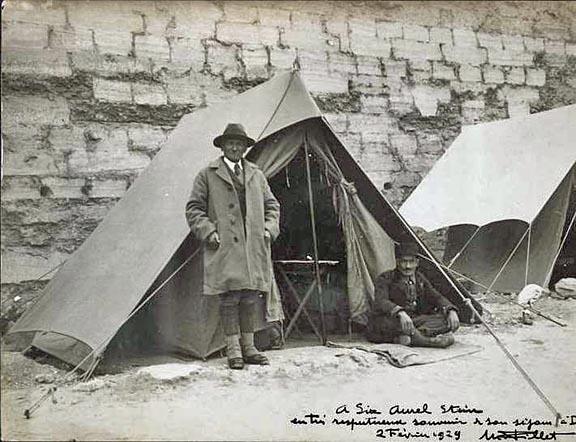

Aurel

Stein in front of his tent in Gulmarg in 1929

For 29 years, when not traveling Stein lived in tents at Gulmarg near Srinagar in Kashmir. Here he wrote all his expedition reports.

When I reached Kashmir in May 1900 Mohand Marg, my mountain retreat

of former seasons, was still covered with snow. My knowledge of

Kashmir topography, however, stood me in good stead, and after a

short search at the debouchure of the great Sind Valley I found near

the hamlet of Dudarhom Gulmarg, a delightfully quiet grove by the

river-bank where I could pitch my tents. There under the shade of

majestic Chinars and within view of the snow-covered Mount Haramukh,

I was soon hard at work from morning till evening.

The few weeks

which remained to me in Kashmir were none too long for the literary

tasks that had to be completed before my departure. For over ten

years past I had devoted whatever leisure I could spare from official

duties to work on the Sanscrit text of Kalhana's great poem

"Chronicle of the Kings of Kashmir."

On the 23rd of May I completed the last of the tasks for the sake of

which I had retired to my peaceful camping-ground. The date fixed for

my start was drawing near, and with it came the necessity for

returning to bustling Srinagar for the last preparations. Thanks to

the convenient water-way provided by the Anchar Lake, and the ancient

Mar Canal, a single night passed in boats sufficed to bring me into

the Kashmir capital.

Ram Singh, the Gurkha Sub-Surveyor, whose

services Colonel St. George Gore, R.E., the Surveyor-General of

India, had very kindly placed at my disposal, together with a

complete outfit of surveying instruments, joined me punctually on the

day of my arrival at Srinagar.

On the 28th of May arrived Sadak

Akhun, the Turkestan servant whom Mr. George Macartney, C.I.E., the

British representative at Kashgar, had been kind enough to engage for

me. He had left Kashgar in the first half of April and came just in

time to start back with me. He was to act as cook and `Karawan-bashi

' combined.

On the morning of the 31st of May sixteen ponies were ready to

receive the loads which were made up by our tents, stores,

instruments, &c. Formidable as this number appeared to me,

accustomed as I was to move lightly on my wanderings in and about

Kashmir, I had the satisfaction to know that my personal baggage

formed the smallest part of these impedimenta.

Leaving

Srinagar May 1900

Srinagar -Gilgit -Baltit-Karimabad

Hunza -Tashkurgan- Kashgar

For

the Route see the Google

Map

540 km

May

31– June

29, 1900

Sand-buried

Ruins of Khotan

Today one can drive on the Chinese-built “Friendship Highway” to Kashgar in a few days, in Stein's time the distance of 540 km had to be negotiated on foot along the old Caravan Route ponies carrying the “goods”, of which Stein had a good load. He required 2 months. I will, for brevety's sake spare the reader Stein's full description of this journey.

|

|

|

|

However, already on the second day he had to cross the modest Tragbal pass (3630 m) and encountered a most difficult situation,which I will let him tell himself:

Tragbal Pass - Carrying the Ponies Across a Snow Bridge

The road, after leaving the straggling line of wooden huts which form

the Bazar of Bandipur, leads for about four miles up the open valley

of the Madhumati stream. At a height of about 9,000 feet a fine

forest of pines covers the spur and encloses a narrow glade known as

Tragbal. Here the snow had just disappeared, and I found the damp

ground strewn with the first carpet of Alpine flowers.

A crude

wooden rest-house begrimed with smoke and mold gave shelter for the

night, doubly welcome, as a storm broke soon after it got dark. The

storm brought fresh snow, and as this was sure to make the crossing

of the pass above more difficult I started before daybreak on the 1st

of June.

A steep ascent of some two thousand feet leads to the

open ridge which the road follows for several miles. Exposed as this

ridge is to all the winds, I was not surprised to find it still

covered with deep snowdrifts, below which all trace of the road

disappeared. Heavy clouds hung around. The snow remained fairly hard.

Soon, however, it began to snow, and the icy wind which swept the

ridge made me and my men push eagerly forward to the shelter offered

by a Dak runners' (mail man) hut. The storm cleared before long, but

it sufficed to show how well deserved is the bad repute which the

Tragbal (11,900 feet) among Kashmirian passes.

For the descent

from the pass I was induced by the 'Markobans' owning the ponies to

utilise the winter route which leads steeply down into a narrow

snow-filled nullah. Though the ponies slid a good deal in the soft

snow of the slope, we did not encounter much difficulty until we got

to the bottom of the gorge. Here the snow bridges over the stream had

begun to give way, and the high banks of snow on either side were in

many places uncomfortably narrow.

At last our progress was

stopped at a point where the stream had washed away the whole of the

snow vault. To take the laden animals along the slatey and

precipitous side of the gorge, which was free from snow, proved

impracticable. To return to the top of the gorge, and thence follow

the proper road which descends in long zigzags along a side spur,

would have cost hours. So the council of my `Markobans,' hardy

hill-men, half Kashmiri, half Dard, decided to try the narrow ledge

of snow which remained standing on the right bank of the stream.

The

first animal, though held and supported by three men, slipped and

rolled into the stream, and with it Sadak Akhun, who vainly attempted

to stem its fall. Fortunately neither man nor pony got hurt, and as

the load was also picked out of the water the attempt was resumed

with additional care.

Making a kind of path with stones placed at

the worst points, we managed to get the animals across one by one.

But it was not without considerable anxiety for my boxes, with survey

instruments and similar çontents, that I watched the operation.

Heavy rain was falling at the time, and when at last we had all the

ponies once more on a safe snow-bridge, men and animals were alike

soaked. By one o'clock I reached the Gorai rest-house, down to which

the valley was covered. with snow; having taken nearly seven hours to

cover the eleven miles of the march.

After many like adventures the small caravan reached Kashgar after

dark on June 29,1900 – and found the gates of the city already

closed.

Sand-buried

Ruins

Kashgar

Jun

29-Sep 12, 1900

Under the Macartneys's Roof

Kashgar was the entry point to the vast desert area of the Taklamakan, where Sven Hedin (1890-1902) and others had discovered numerous archeological sites dated to 800 BC -600 AD buried in the sands. Polyglott Stein was the best educated and most thorough of these explorers. He was especially eager to uncover manuscripts.

The cheerful impressions of that first evening under Mr. Macartney's hospitable roof in Chini Bagh (Chinese Garden) were a true indication of the happy circumstances under which the busy weeks of my stay at Kashgar were to pass. Chini-Bagh had been a simple walled-in orchard with a little garden house, such as every respectable Kashgari loves to own outside the city walls, when Mr. Macartney, more than ten years before my visit, took up the appointment of the Indian Government's Political Representative at Kashgar. Continuous improvements effected with much ingenuity had gradually changed this tumbledown mud-built garden house into a residence which in its cosy, well-furnished rooms now offered all the comforts of an English home, and in its spacious out-houses and "compound" all the advantages of an Indian bungalow.

Here Stein spent 2 months assembling his caravan, buying camels, acquiring with Macartney's help and advice reliable servants and, for him more excting, studying Sanscrit and Turki. He did not speak Chinese. Macartney provided him with a Ssu-chieh, a scholar as translator from whom he quickly learned a minimum of the all-important Chinese etiquette.

On Sep 12, 1900 I finally set out from Kashgar for the journey to

Khotan. Avoiding the ordinary caravan route, I chose for the march to

Yarkand the track which crosses the region of moving sands around the

popular shrine of Ordam-Padshah from the north and joins the main

road from Kashgar and Yangi-Hisar at the oasis of Kizil."

Sand-buried

Ruins

Yarkand

Sep 17 – 26, 1900

A Chinese Dinner Party

A march of about eighteen miles brought me on the 17th of September from Kokrobat into Yarkand. About three miles from the city, I found the whole colony of Indian traders, with Munshi Bunyad Ali at their head waiting to give me a formal reception. Most of the traders from the Punjab had already left for Ladak. All the same it was quite an imposing cavalcade, at the head of which I rode into Yarkand.

They were all in their best dresses, decently mounted, and unmistakably pleased to greet a `Sahib.' So it was only natural that they wished to make some show of him. Accordingly I was escorted in great style through the whole of the Yangi-Shahr, or " New City," and the Bazaars.

Then we turned off to the right and rode round the crenellated walls of the " Old City " into an area of suburban gardens. Here lies the Chini-Bagh which Mr. Macartney had in advance engaged for my residence. It proved quite a summer-palace within a large walled-in garden., Passing through a series of courts, I was surprised to find a great hall of imposing dimensions, with rows of high wooden pillars supporting its roof. Beyond it I entered a series of raised apartments, once the reception-rooms of Niaz Hakim Beg, the original owner of these palatial quarters. The gilding of the latticework screens separating the rooms had faded, and other signs of neglect were numerous. Yet good carpets covered the floors and the raised platforms; tasteful dados ran along the walls, and over the whole lay an air of solemn dignity and ease.

The days which followed my arrival at Yarkand passed with surprising rapidity.

Liu-Darin (`Darin' is the local version of his Chinese title 'Ta jen'), the Amban of Yarkand, was absent on tour when I arrived. But he soon returned, and after the due preliminaries had been arranged, I made my call at his Yamen. I found Liu-Darin a very amiable and intelligent old man. Conversation through a not over-intelligent interpreter is not the way to arrive at a true estimate of character. But somehow Liu-Darin's manners and looks impressed me very favourably. On the next day I received the return visit of the old administrator, and found occasion to show him the Si-yu-ki of Hsüen-Tsiang and to explain what my objects were in searching for the sacred sites which the great pilgrim had visited about Khotan, and for the remains of the old settlements overwhelmed by the desert. It was again reassuring to find how popular the figure of the pious old traveller still is with educated Chinese.

On the 22nd of September Liu-Darin insisted on entertaining me at a Chinese dinner. Well-meant as the invitation no doubt was, I confess that I faced it with mixed feelings. My Kashgar experiences had shown me the ordeal which such a feast represents to the average European. However, things passed better than I had ventured to hope. The dinner consisted of only sixteen courses, and was duly absorbed within three hours. It would be unfair to discuss the strange mixture of the menu, especially as I felt quite incompetent to analyse most of the dishes, or the arrangements of the table. Having regard to my deficient training in the use of eating-sticks I was provided with a fork and a little bowl to eat from. As my host insisted on treating me personally to choice bits, a queer collection accumulated on this substitute for a plate. I felt more comfortable when I managed to get it cleared from time to time. For the hot spirit, a kind of arrack it seemed, served in tiny square cups as the only beverage, there was no such convenient depository, and in reply to the challenges of my convives I had to touch it more frequently than I could have wished. Besides my host, two of his chief officials, jovial-looking men, were keeping me company.

Karghalik

50

km south-east of Yarkand

Sep

28-Oct 2, 1900

Karghalik,

the mosque

Waiting for Cash from Kashgar

On Sep 28 by half-past four I had approached Karghalik through a belt of villages rich in orchards and shrines of all kinds. I soon was enveloped by the tangled net of Bazars that form the centre of Karghalik town, and was struck with their comparative cleanliness and the thriving look of the whole place. It is clear at the first glance that Karghalik derives no small amount of profit from its position at the point where a much-frequented route to the Karakorum Passes joins the great road connecting Khotan with Yarkand. After a long search among the suburban gardens to the south I found a large plot of meadow land with some beautiful old walnut-trees that carried me back in recollection to many a pretty village in Kashmir. It was a delightful camping-ground for myself, and, as my people found quarters in a cottage close by and the ponies excellent grazing, everybody was satisfied.

On

the morning of Oct 8

arrived

the consignment of money, sent by Mr. Macartney from Kashgar in

payment for my drafts on Lahore. My halt at Karghalik had been made

partly in expectation of it. With the bags of Chinese silver coin and

the smaller packet of newly-coined gold Rouble pieces, Mr.

Macartney's `Chaprassi' brought home-letters also. He was to return

the next day and carry my own mail to Kashgar.

History

of Karghalik

Khotan

230 km east of Khargalik

Oct

10 -Nov 25,1900 and Apr 4 1901 (on the return)

The Pigeon Shrine and Finding a Garden in Khotan

A long march on the 10th of October was to bring me at last to the

very confines of Khotan. By the time I reached the Mazar of

Kum-rabat-Padshahim (" My Lord of the Sands Station ") we

were again in a sea of sand.

Amid these surroundings the lively

scene that presented itself at the shrine popularly known as "

Pigeons' Sanctuary " (Kaptar-Mazar) was doubly cheerful. Several

wooden houses and sheds serve as the residence for thousands of

pigeons, which are maintained by the offerings of travellers and the

proceeds of pious endowments. They are believed to be the offspring

of a pair of doves which miraculously appeared from the heart of Imam

Shakir Padshâh, who died here in battle with the infidel, i.e., the

Buddhists of Khotan. The youthful son of one of the Sheikhs attached

to the shrine was alone present to tell me the story. Many thousands

had fallen on both sides, and it was impossible to separate the

bodies of the faithful `Shahids' from those of the `Kafirs.' Then at

the prayer of one of the surviving Musulmans the bodies of those who

had found martyrdom were miraculously collected on one side, and the

doves came forth to mark the remains of the fallen leader. From

gratitude, all travellers on the road offer food to the holy birds.

While watching the pretty spectacle I could not help being

reminded of what Hsüantsang tells us of a local cult curiously

similar at the western border of Khotan territory:

Some thirty

miles before reaching the capital, "in the midst of the straight

road passing through a great sandy desert," the pilgrim

describes "a succession of small hills," which were

supposed to be formed by the burrowing of rats. These rats were

worshipped with offerings by all the wayfarers, owing to the belief

that in ancient times they had saved the land from a great force of

Hiung-nu, or Huns, who were ravaging the border. The Khotan king had

despaired of defending his country, when in answer to his prayer

myriads of rats led by a rat-king destroyed over-night all the

leather of the harness and armour of the invading host, which then

fell an easy prey to the. defenders.

" The rats as big as

hedgehogs, their hair of a gold and silver colour," of which

Hsüantsang was told as inhabiting this desert, are no longer to be

seen even by the eyes of the pious. But the locality he describes

corresponds exactly to the position of the `Kaptar-Mazar' relative to

ancient Khotan, amidst dunes and low, conical sandhills

From there onwards lay an unbroken succession of gardens, hamlets and carefully cultivated fields on both sides. The road itself is flanked by shady avenues of poplars and willows for almost its whole length. Autumn had just turned the leaves yellow and red.

On the road the dust lay ankle deep. It was easy to realise the vicinity of a great trade centre from the lively traffic which passed us. I saw strings of donkeys carrying `Zhubas,' the lambskin coats for the manufacture of which Khotan is famous. Few, indeed, were the passers-by that did not ride on some kind of animal—pony, donkey, or bullock. To proceed to any distance on foot must seem a real hardship even to the poorer classes. No wonder that the people see no reason to object to the ridiculously high heels of their top boots. When riding the inconvenience cannot be felt. But to see the proud possessors of such boots waddle along the road when obliged to use their legs is truly comical.

On the morning of the 13th of October I was just about to start from my camp at Yokakun for Khotan when the Beg arrived, whom the Amban, on hearing of my approach, had deputed to escort me. The Beg was in his Chinese gala garb and had his own little retinue. So we made quite a cavalcade, even before Badruddin Khan, the head of the Afghan merchants in Khotan and a large trader to Ladak, joined me a few miles from Khotan town with some of his fellow-countrymen.

The

bazaarliks of Khotan watching our state procession into town

I found a large though somewhat gloomy house, but none of the attractions of my Yarkand residence. The maze of little rooms all lit from the roof and badly deficient in ventilation could not be used for my own quarters. Outside in the garden there was a picturesque wilderness of trees and bushes, but little room for a tent and still less of privacy. So after settling down for the day and despatching my messages and presents for the Amban, I used the few remaining hours of daylight for a reconnaissance.

There is a charm about the ease with which, in these parts, one may invade the house of anyone, high or low, sure to find a courteous reception, whether the visit is expected or otherwise. So when after a long ride through suburban lanes and along the far-stretching lines of mud-built fortifications, about half a mile from Tokhta Akhun's, I came upon another residential garden, enclosed by high walls and surrounded by fields, I did not hesitate to have my visit announced to the owner. Through a series of courts I entered a large and airy reception hall, and through it passed into a large open garden that at once took my fancy. Akhun Beg, a fine-looking, portly old gentleman, received me like a guest', and when informed of the object of my search readily offered me the use of his residence. I had disturbed him in the reading of a Turki version of Firdusi's Shahnama. My acquaintance with the original of the great Persian epic seemed to win for me at once the goodwill of my impromptu host, and I hesitated the less about accepting his offer.

The oasis of Khotan has from very early times been the largest and most important cultivated territory in the south of the Tarim Basin. To this fact we owe the ample information which the Chinese records furnish as to its ancient history.

Stein

spend several weeks in Khotan preparing for his winter expedition

into the desert. Khotan is described in his extensive

reports in “Ancient

Khotan, volume 1”,

too

voluminous to reproduce here:

Geography,

cultivation and industry

Population

of the oasis

and

its origins

History

according to Hsüantsang, Tibetan sources, and later Chinese

records

Buddhist Sites around Khotan

Yotkan

10 km west of Khotan

Oct. 15 and Nov 24. 1900

Trying to Find the Ancient Capital of Khotan

Yotkan was the capital of the Khotan kingdom from the 3rd to the 8th

cent AD. Stein found that Yotkan had been plundered thoroughly by

local treasure hunters. This load was all he was able to collect or

purchase and ship home:

Sand

buried Ruins of Khotan

Terracotta

fragments from Yotkan.

Throughout

his travels Stein also performed anthropometric measurements on the

local population.

This is an early sample from Yotkan.

Ancient

Khotan, volume 1

Search

for the ruins of the city

List

of purchased antiques

Dandan-Uiliq

100

km north-east of Khotan

Dec

7, 1900 – Jan 3, 1901

Stein's First Major Discovery

On the morning of December 7, a misty and bitterly cold day, I set out for the winter campaign in the desert. In order to reach Dandan-Uiliq I had decided on the route via Tawakkél, which, though longer than the track leading straight into the desert which reduced the extent of actual desert-marching. At Tawakkel (Dec 10-12, 1900) thanks to the stringent instructions issued by Pan-Darin, I was able to collect a party of thirty labourers for my intended excavations, together with four weeks' food supply. Owing to superstitious fears and in view of the expected rigours of the winter, these farmers were naturally reluctant to venture so far into the desert, though they appreciated the pay offered, 1 Miskals per diem, which was more than twice the average wages for unskilled labour.

The winter of the desert had now set in with full vigour. In daytime

while on the march there was little to complain of; for though the

temperature in the shade never rose above freezing point, yet there

was no wind, and I could enjoy without discomfort the delightfully

pure air of the desert and its repose which nothing living disturbs.

But at night, when the thermometer would go down to below zero

Fahrenh., my little Kabul tent, notwithstanding its extra serge

lining, was a terribly cold abode. The "Stormont-Murphy Arctic

Stove" which was fed with small compressed fuel cakes (from

London !) steeped in paraffin proved very useful; yet its warmth was

not sufficient to permit my discarding the heavy winter garb,

including a fur-lined overcoat and boots, which protected me in the

open. The costume I wore would, together with the beard I was obliged

to allow to grow, have made me unrecognisable even to my best friends

in Europe. When the temperature had gone down in the tent to about 6

degrees Fahr. below freezing-point, reading or writing became

impossible, and I had to retire among the heavy blankets and rugs of

my bed. There `Yolchi Beg', my foxterrier, had usually long before

sought refuge, though he too was in possession of a comfortable fur

coat of Kashmirian make, from which he scarcely ever emerged between

December and March.

To protect one's head at night from the

intense cold while retaining free respiration, was one of the small

domestic problems which had to be faced from the start of this winter

campaign. To the knitted Shetland cap which covered the head but left

the face bare, I had soon to add the fur-lined cap of Balaclava shape

made in Kashmir, which with its flaps and peak pulled down gave

additional protection for everything except nose and cheeks. Still it

was uncomfortable to wake up with one's moustache hard frozen.

On the fifth such morning, the 18th of

December, after turning a great Dawan, Turdi guided us to his spot,

and a couple of miles further south I found myself amidst the ruined

houses which mark the site of Dandan-Uiliq.

Sand-buried

Ruins

Old Turdi felt quite at home among these desolate surroundings, which he had visited so frequently since his boyhood. It was the fascinating vision of hidden treasure which had drawn him and his kinsfolk there again and again, however scanty the tangible reward had been of their trying wanderings.

The structures more deeply buried in the sand had escaped unopened. It was important to select these in the first place for my excavations, and I felt grateful for Turdi's excellent memory and topographical instinct which enabled him readily to indicate their positions. Guided by this first rapid survey, I chose for my camp a spot from which the main ruins to be explored were all within easy reach.

On the morning of the 19th of December I commenced my excavations by clearing the remains of a small square building immediately to the south of my camp. Turdi knew it as a ' But-khana ' or " temple of idols." A careful examination of the remains of walls which were brought to light on the north and west sides under several feet of sand showed that there had been an inner square cella enclosed by equidistant outer walls twenty feet long, forming a kind of corridor or passage on each side.

Mixed with frequently repeated architectural ornaments there were numerous reproductions in low relievo of the figure of Buddha, in the orthodox attitudes of teaching with hand raised or seated in meditation Other small relievos showed attendant figures in adoration, such as the graceful garland-holding woman rising from a lotus and probably meant for a Gandharvi, which has been reproduced on the cover of this book. Conventional as all these representations are and evidently casts from a series of moulds, they at once arrested my interest by their unmistakable affinity to that style of Buddhist sculpture in India which developed under classical influences.

The clearing of this single small shrine not only yielded some one hundred and fifty pieces of stucco relievo fit for transport to Europe, but supplied me with the indications I needed in order to direct the systematic excavation of structures more deeply buried in the sand.

|

|

|

I proceeded to a group of small buildings buried below six to eight

feet of sand by a fairly high dune. I was able correctly to gauge

their construction and character, though only the broken and bleached

ends of posts were visible above the sand. After some digging we

found a temple, the cella of which was enclosed by a quadrangular

passage about 4.5 feet wide. This passage, which almost certainly

served for the purposes of circumambulation ('pradakshina') common to

all traditional forms of Indian worship. The interior of the cella

was once occupied by a colossal statue made of stucco and painted,

which probably represented a Buddha. But of this only the feet

remained.

The walls of the cella, which must have been of

considerable height, were decorated inside with frescoes showing

figures of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas enveloped in large halos. As

these too were over life-size, only the feet with the broad painted

frieze below them showing lotuses and small figures of worshippers,

could be seen on the walls still standing.

|

|

|

At the foot of the principal base and leaning against it we found

five painted panels of wood, all oblong, but of varying sizes. Even

the imperfect cleaning at the time sufficed to show that these little

paintings represent personages of Buddhist mythology or scenes

bearing on Buddhist worship and legends.

Text from Sand-buried

Ruins, Illustrations from Ancient

Khotan vol 2

|

|

|

It had not needed the discovery of a pictorial representation of a`Pothi' (book) to make me eagerly look out for finds of ancient manuscripts. None had turned up during the excavations of the first three days.

So, on the 22nd of December, I directed my men to the excavation of a structure close by, which by its position and ground-plan as deducible from the arrangement of the wooden posts that were seen sticking out above the sand, appeared to suggest an ancient dwelling-place. By noon, at a depth of 2 ft. from the surface, a small scrap of paper showing a few Brahmi characters was found in the loose sand which filled the building. I greeted it, with no small satisfaction as a promise of richer finds. Barely an hour later a cheerful shout from one of the men working at the bottom of the small area so far excavated on the north-west side of the apartment announced the discovery of a `Khat,' or writing.

Carefully extracted with my own hands and cleared of the adhering sand, it proved a perfectly preserved oblong leaf of paper, 13 inches long and 4 inches high, that had undoubtedly formed part of a larger manuscript arranged in the shape of an Indian `Pothi.' The six lines of beautifully clear writing which cover each side of the leaf show Brahmi characters of the so-called Gupta type, but a non-Indian language.

The interesting find was quickly followed by a series of other

manuscripts either in loose leaves, more or less complete, or in

little sets of fragments. They all showed Brahmi writing of an early

type and had, as their conformity in paper, size and handwriting

showed, originally belonged to at least three distinct `Pothis,' or

books. Their contents were soon recognised by me as Sanskrit. texts

treating of Buddhist canonical matter.

Ancient

Khotan

From Prof. Margoliouth's translation of the Judeo

fragment, it will be seen that the document (718 AD) represents

the much-mutilated fragment of a letter written by a Persian-speaking

Jew, mainly relating to certain business affairs.

Other

Finds and

General Observations

Sand-blown Rawaq Stupa

20

km north-east of Khotan

Jan

3-6, 1901

The examination of the scanty remains at Rawaq had completed the task for which I had set out just a month previously from Khotan. So on the morning of January 6 I dismissed Ahmad Merghen with the last batch of the Tawakkel labourers, and set out with a much reduced caravan for the Keriya river.

Keriya

170 km

east of Khotan

Jan 8-12, and Mar 30 1901 (on the return)

I had originally intended to steer due east from Rawaq, in order to strike the nearest point on the Keriya river, but the rising height of the dunes and the impossibility of getting at water obliged me after the first day to seek the southern route eastwards which the main caravan route follows. By the evening of January 8 the hard-frozen river was at last safely reached.

I decided first to visit Keriya, the head quarters of the District east of Khotan, before commencing other explorations, in order to secure personally the assistance of the local Amban.

Kara-dong, the old site further down the Keriya river, seemed

temptingly near, but in the lonely jungle tracts along the river,

uninhabited except by nomadic shepherds, it would have been

impossible to raise either labourers or the badly-needed supplies.

Four long marches brought us to Keriya through the belt of Toghrak

jungle and scrub accompanying the river's course in the desert.

Ancient

Khotan

Niya Ruins the Great Find

150

km north-west of Endere Ruins

Jan 23-Feb 28, 1901

On January 23 I set out from Niya Bazaar with twenty labourers and a small convoy of additional hired camels to help in the transport of a month's supplies. A three days' march brought me to starting-point for my fresh expedition into the desert. The route lay all along the Niya river, and through the belt of thick forest which accompanies its course.

The march of January 27, confirmed my surmise that the ancient site would be reached by following this direction. For the first five miles or so thick patches of dead forest were encountered between the tamarisk-covered hillocks.

|

|

A rapid inspection showed me that the mode of construction in these buildings [ruin N] was substantially the same as that in the dwellings of Dandân-Uiliq, but their dimensions were larger and the timber framework far more elaborate and solid. I came upon some finely-carved pieces of wood lying practically on the surface, which showed ornamentation unmistakably of the Gandhâra style.

Here, in a position conveniently central for the exploration of the scattered ruins, I pitched my camp. As I retired to my first night's rest among these silent witnesses of ancient habitations my main thought was how many of the precious documents on wood, which Ibrâhim declared he had left behind at the ruin `explored' by him a year before, were still waiting to be recovered.

At sunrise of January 28, 1901 with the temperature still well below zero F I hastened to the ruined building where Ibrahim had a year previously found his ancient tablets inscribed with Kharosthi characters. On ascending the west slope, seen in the foreground of photograph, I picked up at once three tablets inscribed with Kharosthi lying amidst the débris of massive timber which marked wholly eroded parts of the ruined structure. On reaching the top I found to my delight many more scattered about in the sand within the nearest of the rooms still clearly traceable by remains of their walls. The layer of drift-sand that had spread over the tablets since Ibrahim had thrown them down here a year before, was so thin as scarcely to protect the topmost ones from the snow that lay about one inch deep over the more shaded portions of the ground. It dated, no doubt, from the snowfall which I had encountered on my way from Keriya to Niya eight days earlier.

Ibrahim seemed scarcely less elated than myself at seeing his statement confirmed, and the good reward I had promised him thus assured. He at once pointed out to me that the find-place of the relics was not in this room, where he had thrown them away in utter ignorance of their value, but in the south corner of the room immediately adjoining eastwards. There, in a little recess about 4 feet wide, formed between the fireplace, well recognizable above the sand, and the wall dividing rooms, he had come upon a heap of tablets while scooping out the sand with his hands in search of `treasure'.

The

hundred and odd inscribed tablets with which I returned to camp from

my first day's work amid these ruins represented a harvest far more

abundant than I could reasonably have hoped for. The remarkable state

of preservation in which a considerable portion of them made it easy

for me, even during the first rapid examination on the spot, to

recognize certain main features in their outward arrangement; and the

few hours of study which I was subsequently able to devote to them in

my tent during the bitterly cold evenings soon familiarized me with

some aspects of their use as an ancient writing material.

Ancient

Khotan

|

|

|

The first few hours' work was rewarded by the discovery of complete Kharosthi documents on leather. The oblong sheets of carefully prepared smooth sheepskin, of which altogether two dozen came to light here, showed different sizes, up to 15 inches in length. They were invariably found folded up into neat little rolls, but could be opened out in most cases without serious difficulty.

These documents have a special interest as the first specimens as yet discovered of leather used for writing purposes among a population of Indian language and culture. Whatever the religious objections may have been, it is evident that in practice they had no more weight with the pious Buddhists of this region than with the orthodox Brahmans of Kashmir, who for centuries back have used leather bindings for their cherished Sanskrit codices.

The tablets showed throughout the characteristic peculiarities of that type of Kharosthi writing which in India is invariably exhibited by the inscriptions of the so-called Kushana or Indo-Scythian kings. The period during which these kings ruled over the Punjab and the regions to the west of the Indus falls within the first three centuries of our era.

I felt absolutely assured as to their high antiquity and exceptional value. And yet during that day's animating labours and as I marched back to camp in the failing light of the evening, there remained a thought that prevented my archæological conscience from becoming over-triumphant. It was true that the collected text of the hundred odd tablets, which I was carrying away carefully packed and labelled as the result of my first day's work, could not fall much short of, if it did not exceed, the aggregate of all the materials previously available for the study of Kharoshthi.

Discoveries in a Rubbish Heap – His First!

|

|

|

Promising as the finds were which my previous "prospecting" had yielded, I little anticipated how extraordinary rich a mine of ancient records I had struck in the ruin I proceeded to excavate. On the surface there was nothing to suggest the wealth of relics contained within the half-broken walls of the room, 23 by 18 feet large, which once formed the western end of a modest dwelling-place. But when systematic excavation, begun at the north-western corner of the room, revealed layer ufon layer of wooden tablets mixed up with refuse of all sorts, the truth soon dawned upon me. I had struck an ancient rubbish heap formed by the accumulations of many years, and containing also what, with an anachronism, we may fitly call the "waste-paper" deposits of that early time.

It was not sand from which I extracted tablet after tablet, but a

consolidated mass of refuse lying fully 4 feet above the original

floor, as seen in the photograph. All the documents on wood, of which

I recovered in the end more than two hundred, were found scattered

among layers of broken pottery, straw, rags of felt and various woven

fabrics, pieces of leather, and other rubbish.

- Yet trash piles

would become the most abundant sources of ancient documents in

Stein's expeditions....

|

|

|

The most convincing proof of the dominating influence which Indian

art exercised on the industries represented in this ancient

settlement was furnished by a wool rug and the ornamental woodcarving

of the chair shown above.

Their close agreement with decorative

motives found in Gandhâra sculptures of the first centuries of our

era was welcomed by me from the first as valuable confirmation of the

chronological evidence deducible from the Kharosthi writing of the

tablets. In another direction, too, this piece of ancient art

furniture serves as useful testimony. Though not of intrinsic value

in its material, and on that account no doubt left behind when the

dwelling was abandoned, it yet shows by its workmanship that those

who once lived here were people in affluent circumstances.

Extensive

references to Niya 1901:

Find

of inscribed tablets

Residences

Discovery

of an ancient

Rubbish

Heap

Documents

Wood and Leather

Chinese

Documents

Endere Ruins

130

km north-east of Niya Bazaar

Feb 26, 1901

Stein visited Endere twice. In 1901 he explored only the Tang fort and then returned to visit Niya Bazaar and Karadong. In 1906 he came back and found, as ususal in the trash pilles, various manuscripts.

Kara-Dong

130 km

south-west of Niya Ruins and 240 km north of Keriya

March 13-17,

1901

Karadong had been discovered by Sven Hedin in 1896.

Stein writes:

Leaving my 'goods train' of camels to follow behind,

I covered on February 26 to March 2, 1901 the distance from Niya back

to Keriya, some 130 km, in two stages. After a few days in Keriya we

reached the remains of Kara-dong, 240 km north on March 13, 1901. It

proved a disappointment consisting mainly of one ruined quadrangle.

He abandoned the site on March 17, 1901 to return in 1907.

Wooden

gateway to Stein's partially excavated quadrangle 1901

Return: Khotan-Kashgar-Osh

(Fergana) -Tashkent- by Train

to London

See

Placemarkers

on Google

Earth

May 12

-Jul

2, 1901

Of the journey which brought me back to Kashgar and thence through Russian Turkestan to England, the briefest account will suffice: Six rapid marches, diversified by the rare experience of gathering rain-clouds, carried me to Yarkand, where to my caravan had safely preceded me. It was fortunate that, owing to the short stay I was obliged to make at Yarkand for the settlement of my followers' accounts and debts, my collections escaped serious risk of damage from an abnormal burst of rain such as this region had not seen for long years. The downpour of two days and two nights turned all roads into quagmires and caused the mud-built walls of many houses in town and villages to collapse.

A ride of three days, in advance of my caravan, sufficed to bring me

by May 12 to Kashgar, where, under Mr. Macartney's hospitable roof,

the warmest welcome greeted me.

The Government of India in the

Foreign Department had obtained for me permission from the

authorities in St. Petersburg to travel through Russian Turkestan and

to use the Trans-Caspian Railway for my return to Europe. I had also

been authorized to take my collections for temporary deposit to

England.

After a fortnight of busy work my preparations for the

rest of the journey were completed, and all my antiques safely packed

in twelve large boxes. They were duly presented at the Russian

Consulate for customs examination—a most gently conducted one—and

then received their seals with the Imperial eagle, which in spite of

a succession of Continental customs barriers, I succeeded in keeping

intact until I could unpack their contents in the British Museum.

On May 29, 1901, exactly a year after leaving Srinagar, I started from Kâshgar for Osh, the nearest Russian town in Farghana. By keeping in the saddle or on foot from early morning until nightfall I managed to cover the route from Kâshgar to Osh, reckoned at eighteen marches, within ten days. I arrived at Osh on June 7. Two days later, at Andijan, I reached the terminus of the Trans-Caspian Railway, which was now to carry me and my antiques in comfort and -safety towards Europe.

The few but delightful days which I spent at Samarkand mainly in visits to the great monuments of architecture of Timur's period, were unfortunately too short to permit of more than a glimpse of the important ancient site known as Afrosiyâb.

A day's stay at Merw allowed me to touch ground full of memories of ancient Iran. Then past the ruins of Göktepe, an historical site of more recent memories, the railway carried me to Krasnowodsk. From there I crossed the Caspian to Baku, and, finally, after long days in the train, I arrived in London on July 2, 1901.

There I was able to deposit the antiques unearthed from the desert sands in the British Museum as a safe temporary resting-place. It was a relief to find that the long and partly difficult transit of close on six thousand miles had caused but slight damage even to those most fragile of objects the reliefs of friable stucco, and that the eight hundred odd negatives on glass plates brought back as the photographic results of my journey were safe. But I soon realized that the successful completion of my exploratory labours, which had been rewarded by results far beyond long-cherished hopes, was also the commencement of a period of toil, the more trying because the physical conditions under which it had to be done were so different from those I had gone through.