Icons

and Churches of the Old Rus'

An

Introduction

Icons

in the Eastern Church and especially in Russia are living

manifestations of the portrayed saint or event. Spiritually they are

much more than a painting of Christ, the Virgin, or the

Transfiguration. They have the spiritual power of healing and

consoling, or of protecting the land or a town better than an army.

No wonder then that Orthodox believers venerate their icons with a

faith and fervor that we have mostly forgotten in the enlightened

Latin West - Bavaria comes to mind as an exception...

-

|

|

One

of the most haunting Russian icons is Rublev's

Christ from the Deesis in Zvenigorod.

In a psychological sense an icon is a two-dimensional

image, a reflexion of the deepest substrate of the human soul and

of the Russian dusha in

particular. They allow one to gain an insight into much more in

Russia than her Orthodx faith. Our art-historical curiosity,

however, is entirely irrelevant to the Church and its believers,

and it becomes a real challenge to elucidate the provenance and

dates of a particular icon – as I have valiantly tried to

do.

The

painting of icons began in the Christian Near East in the 5th

century.

Some of the oldest (6th

cent)

are in the Monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai. They appear

in Kievan Rus' in the 10th

century.

By the 14th

century

a specific Russian style had evolved in Northern Rus', which

culminates in the paintings of Theophanes the Greek, Dionysus,

and most gloriously in those of Andrei Rublev and his school in

the early 15th

century.

Since the 1920s many icons have been moved to the safety

of museums, have been freed of their silver bemas

(precious

metal coverings), cleaned

of the soot of candles and kisses and subjected to the scrutiny

of modern restaurateurs. Copies replaced them in the churches.

|

-

|

|

The

greatest Russian icons have a sweetness which is not found in

comparable religious paintings of Greece, Bulgaria, or Syria.

Influences from the more relaxed traditions of Macedonia,

Georgia, and Byzantine Italy are, however, noticable in the 12th

century.

By the time Italian Renaissance architects began working in

Moscow in the 17th

century

icon painting had artistically

and esthetically

declined

- which albeit has not diminished the spiritual power of even the

latest paintings.

For

visual reasons I have tried to associate specific icons with the

churches they originated from, an often haphazard endeavor,

because these miraculous images were frequently moved to other

places by the powerful of the land – viz.,

the

Soviet authorities who hid them in the basements of their

museums.

My

collection is ordered by their location and date.

Andrei

Rublyev, Our Lady of Vladimir, 1408

|

-

|

The

precious icons in the possession of a church are displayed in an

Iconostasis, a high wood or masonry wall which separates the Holy

of the Holiest from the ordinary world. In most churches the

iconostases are heavily encrusted with repoussé gold or

silver bemas.

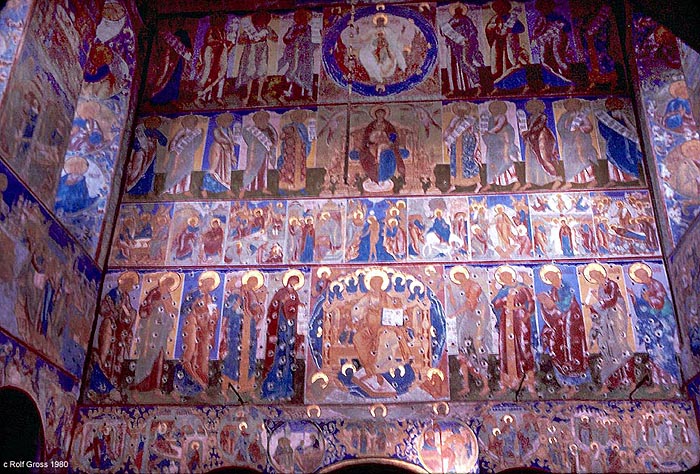

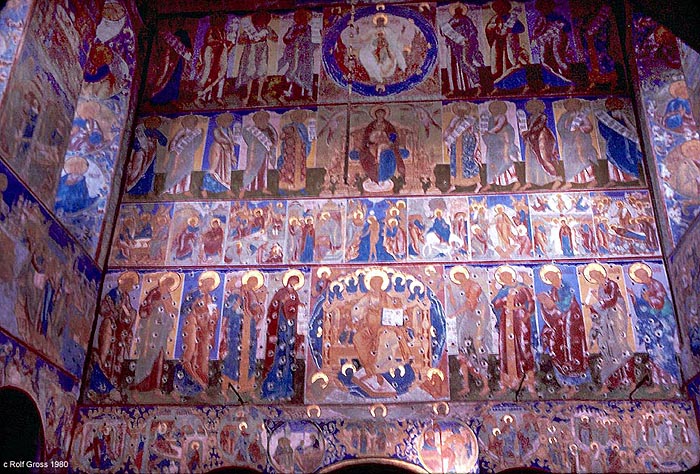

This is an exceptional fresco which has recently been rcovered

from under plaster. The images are arranged in several tiers

(“ranges”): In the lowest range the local icon is

displayed on the opposite side of the “Golden Door”.

The icons of the next tier, the “Deesis”, show a

canonized arrangement of large, elongated images of saints,

archangels, the Virgin and the Baptist on both sides of Christ in

Majesty, who resides in an elliptical mandorla.

Rostov

Veliki, Church of the Resurrection, 17th

century.

|

|

For

one of the most splendid iconosasis see Andrei Rublyev's Iconostasis

of the Trinity Cathedral in the Sergiev Lavra.

Above

the Deesis is a tier of Feast Days, smaller icons depicting the high

holidays of the Orthodox Faith. The highest range occupies images of

Old Testament prophets and church fathers. Closer

scrutiny of the Feast Days of the Trinity-Sergiev iconostasis shows

that the Eastern Church celebrates holidays which are barely

mentioned in the West, like the Assumption of the Virgin and her

presentation in the temple.

-

|

|

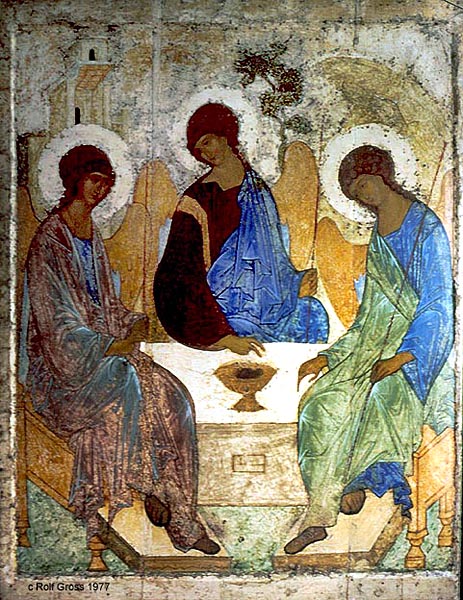

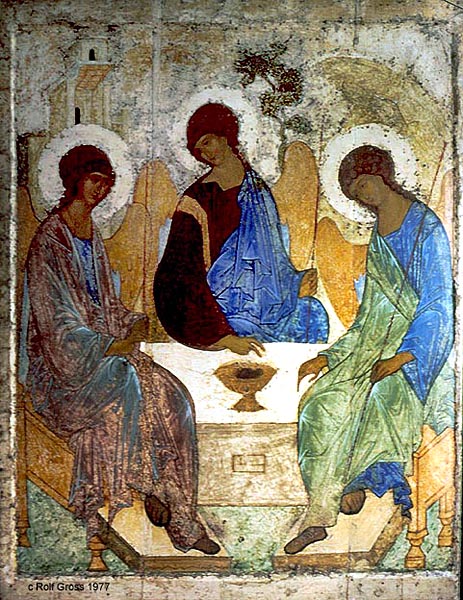

These pecularities are due to

the ever present veneration of the Mother of God in Russia and

also to a body of complex edicts which, for example, forbade the

presentation of God Father. The prophetic icon of the Trinity in

the Old Testament – Abraham receiving three messengers from

God - is such a case: it represents the “New Testament”

Trinity, which is very rarely present in the older sactuaries.

Arguably the most revered icon

of Russia is the local icon of the Trinity Cathedral in the

Sergiev Lavra, next to the door in the lowest range of the

iconostasis:

Andrei

Rublyev, Old Testament Trinity, Trinity Cathedral of the Sergiev

Lavra, 1425.

|

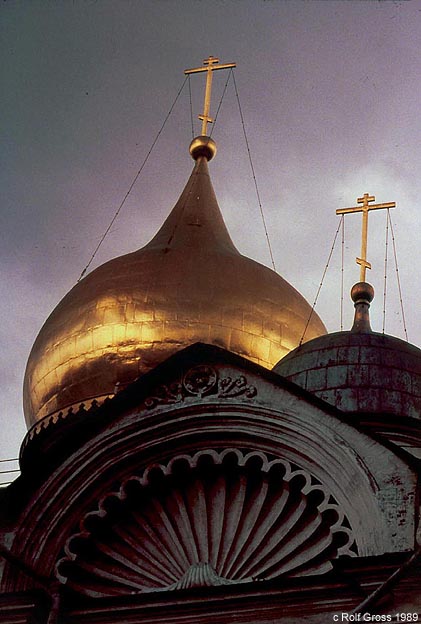

The

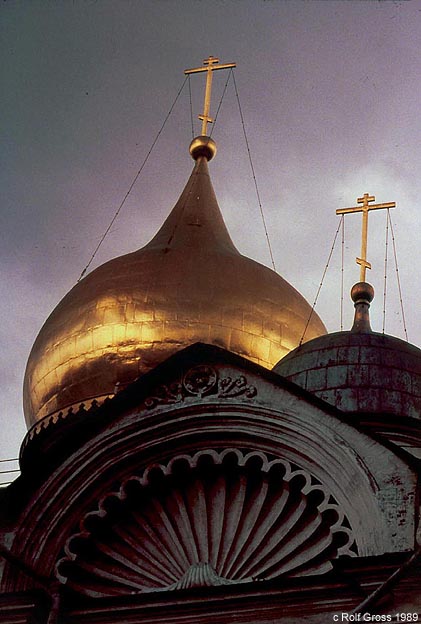

Churches that

house these images are equally different from the churches in the

West. The Roman basilica, designed for large crowds – and the

display of Byzantine imperial might - has never acquired a foothold

in Russia proper. They do exist in Georgia, Greece, and the Balkans.

Russian churches are, like in ancient Greece, “Jewel Boxes of

the Saints”, enclosures for the Holy Images.

-

|

Like

the icons they can be seen as three-dimensional mandalas

expressing another level of images of the soul. My favorite

example is the small church in the Andronikov Monastery (12th

cent),

the oldest surviving church in Moscow. Early Churches in Novgorod

and in Vladimir show the same architectural style: a square floor

plan, a varyingly high rectangular body with a single drum and

cupola crowning this iconic architecture.

Church

of the Savior in the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow (12th

cent)

|

|

-

|

|

In the copula of their frescoed

interior resides the Holy Face of Christ the Savior, the center

of the mandala.

The

interior of the Church of the Resurrection in Rostov Veliki.

|

-

|

|

Historically

this design first appeared in the 11th

century

in Vladimir, probably built by Georgian architects, in Novgorod,

where Macedonian craftsmen worked, and finally - indigenously

Russian - in the 12th

century

in the many small churches of Pskov.

The

oldest churches in Russia were constructed of wood and were

invariably destroyed by frequent fires. The surviving wooden

churches are from the 18th

century

and were rescued and conserved only in the past fifty years.

Dimitry

Cathedral, Valdimir, 1194-1197

|

-

|

Moscow,

which historically was the last capital of the Old Rus', became

architecturally important only in the 14th

to

16th

century.

With one or two exceptions the

churches of the Kremlin were built by Italian architects hired by

the Tsars. Astonishingly, they faithfully adopted the tastes and

ideas of their new clients, only a few outside ornaments remind

one of the contemporary Renaissance architecture of their

homeland.

In

the 18th

century

Russian architecture espoused the Baroque, a by then fashionable

style more akin to the mentality and taste of the powerful elite

than the formal severity of the enlightened Renaissance. With

Peter the Great the time of the Old Rus' came to an end.

The

Archangel Cathedral in the Kremlin of Moscow, 1504 - 1508

|

|

-

|

|

Finally I have to confess that,

seduced by the beauty of the photographs I found in the internet,

I included a number of buildings and places, which I did not

visit and would have disregarded architecturally otherwise. I had

forgotten how beguilingly glorious the colorful fairy towns and

their golden copulas can appear in the monotonous, flat Russian

landscape, especially after having been renovated in the last

fifteen years.

The

ill-famed Solovetsky Monastery on an island in the White

Sea.

Founded

in 1429 it was the greatest citadel of Christianity in the

Russian North before being turned into a Tsarist place of exile

and later into Soviet labor camp.

This

photo is from skyplace.org

All

other photos RWFG 1977-1989

|

This

website is based on a Google-Earth file which is linked to in each

chapter. It shows the location of the places and many additional

Panoramio photos that annotate the pictures presented here.

Last

not least this collection is dedicated to the memory and to the

enjoyment of the many friends in Moscow who hosted and drove me

around during eight extended visits between 1969 and 1989. I came as

a physicist invited by the Soviet Academy of Sciences and left wiser

and enriched by the visual insights into Russia's enigmatic culture.

An

excellent review of the subject appeared just at the right time with

a

large exhibition at the Louvre in Paris:

Holy

Russia

Russian Art from the Beginnings to Peter the

Great

March 5 to May 24, 2010

RWFG,

March 2010