The images are copies from a catalogue by Shalva Amiranashvili, Aurora, Leningrad, 1969 (out of print)

High and late medieval Georgian metal work and enamel objects are the artistic culmination of Georgian religious art. They are only approached by contemporary Byzantine works from the imperial workshops in Constantinople. The Georgian objects are distinguished by their great freedom, liveliness of composition, and color. They invariably treat sacred subjects, images and lives of saints, tetramorphs, Christ on the cross, and scenes from the New Testament. They served as icons but most often the small plaques were affixed to the bemas (metal shields) of large icons. Some are in gold or silver repoussé, but the most beautiful ones are enamel cloisonnes of an unsurpassed gaity of color. Most come from very small villages where a single family was the keeper and protector of the holy image. - Missing are icons from Svaneti which are still in private hands there. A first illustrated catlogue of Svanetian icons by Rolf and Brigitta Schrade will appear in October 2007.

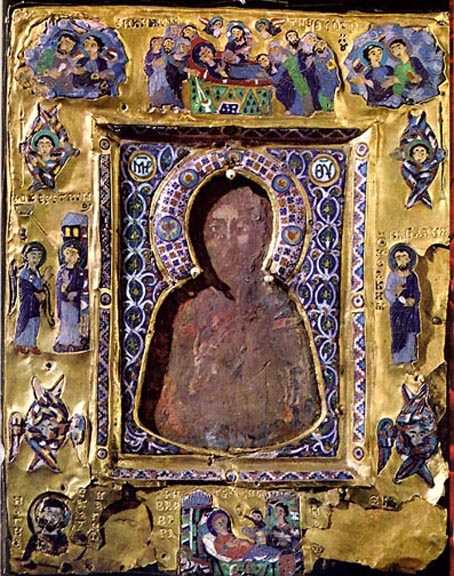

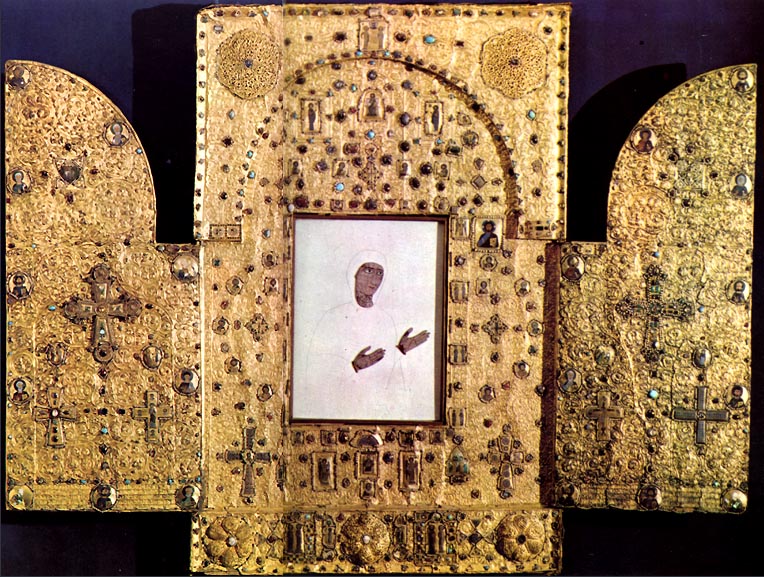

The gold bema of the Kartskheli Icon (13th century) is one of the most splendid examples in the Museum’s collection. It shows all the typically Georgian characteristcs and the arrangement of enamel-cloissoné plaques describing scenes in the life of the Mother of God surrounding a badly deteriorated, painted image of the Virgin.

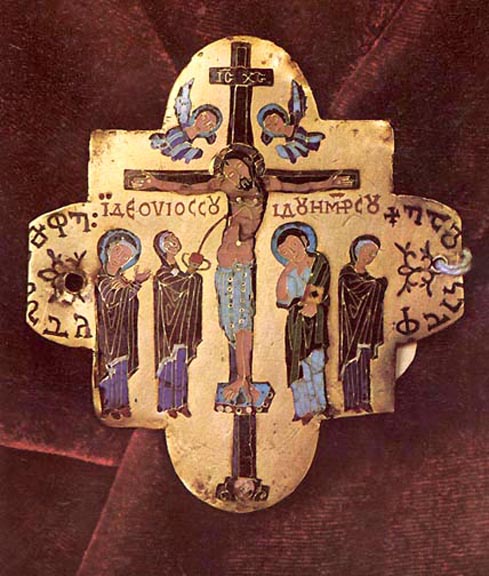

An early Crucifixion cloissoné plaque (7-8th cent) from the bema of the Khakhuli Triptych (see further below).

st in Limbo (descending into the underworld), a celebrated subject of the Eastern Orthodox Church. An early champléve and cloisone gold plaque from Martvili, late 10th century. Inscriptions in Greek, showing the strong influence of Byzantium.

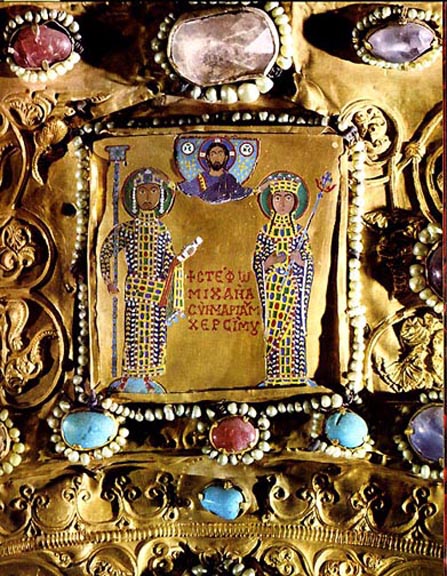

Pectoral cross from Martvili (8th - 9th cent) in gold repoussé (Christ) combined with enamel, prescious stones, and pearls.

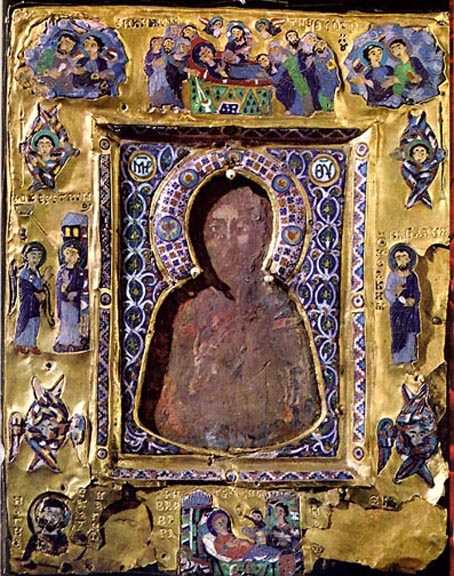

A larg processional cross from Ishkhani (973), cast silver gilded, showing the sculptural sensibilies of the 10th century: sparse, almost rigid, nevertheless of great expressiveness.

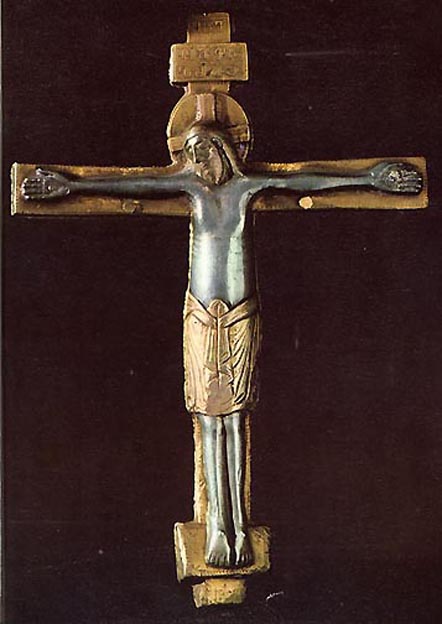

This cloisonné plaque of King Michael VII Parapinak and his wife Maria was probably made for them in Constantinople (inscription in Greek). Another attachement from the Khahkhuli Triptych. Late 11th cent.

Cross from Shemokmedi (Khakhuli icon (?)) , champléve and cloissoné enamel on gold. Early 10th century. Greek and Georgian inscriptions.

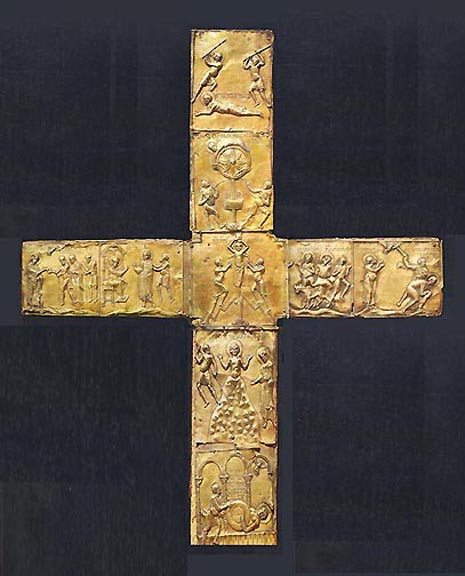

Nine repoussé plaques from the original altar cross in Sveti Skhoveli in Mtskheta (1030). Scenes from the miserable life of St George (his appearance before Emporer Diokletian, being flailed, bound to a wheel, cooked, roasted, and finally crucified). - He was one of the warrior saints. - I guess these apocryphal legends were intended to make him into a martyr. - The Mtskheta Cross had been disassembled and some plaques were lost in the process. They are here not neccessarily in the original order.

The piece sine-qua-non among Georgian icons. The gilded-silver Khakhuli Triptych of the Virgin, 147cm x 202 cm when opened, embellished with innumerable enamel plaques from earlier centuries, precious stones, filigree ornaments, and pearls. The icon of the Virgin at its center is lost, only her enamel(!) hands and face survive. It was once the largest (54 x 41cm) cloisonné enamel in existence. The triptych was commissioned by King Demetre I in 1130.

A copper copy of this repoussé icon, a present from a Georgian friend, hangs above my desk. Unusal for its free layout of Christ’s Descent from the Cross, his Entombment, and the Holy Women on Easter Morning in one 22 x 22 cm square. These three themes of the Easter Story have never been told elsewhere like this, very Georgian! From Shemokmedi, silver, 11th century.

Two champléve enamel medallions, Christ and St. Demetrius, from the Jumati Icon of the Archangel Michael, 12th century.

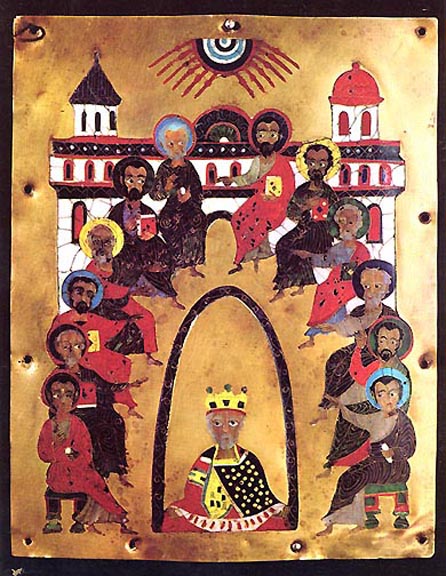

Descent of the Holy Ghost onto the Apostles, a rare subject in the Eastern Church. The “King of Hearts” seems the actual center. Gilded cloissoné, 12th century.

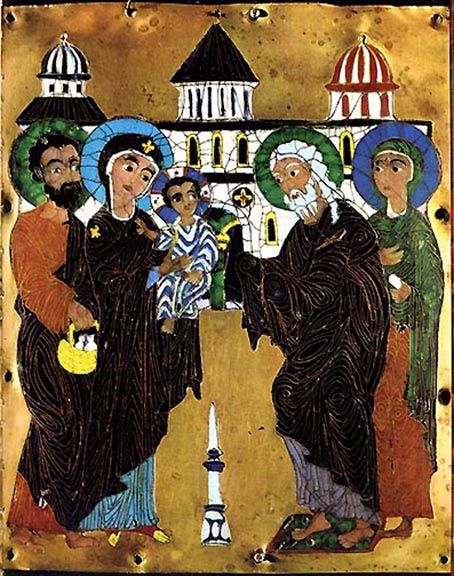

Presentation in the Temple. Late 12th century cloisonné enamel. Georgian colors at their peak. The artist’s playfulness is taking over, viz., the basket with milk bottles for the blue-and-white baby which Joseph holds in his right!

St. George threatening to kill the Dragon who is happily restrained with a red wool thread by the Queen. Cloisonné enamel, 15th century.

This large (2-m high) repoussé Altar Cross from Chkhari now stands in Sveti Skhoveli, Mtskheta - Late 15th century. The pleasure of telling the stories of Christ’s life has nearly completely overwhelmed the formal layout by the artist.

Postscript:

These treasures have an improbable history. When in 1922 the

government of the first Free Georgia fled from the Soviet invasion to

the West, two noblemen - I believe

they were a Dadeshkeliani from Svanetia and a Dadiani from Mingrelia

- took these and other religious treasures to France.

Some pieces were stolen and disappeared in the international art

market (some are in New York some in Paris museums), the bulk was

hidden in a bank safe. - After Stalin’s ascension

and the complete subjugation of Georgia, Stalin negotiated a return

of the objects with the French. It must have been during the

intellectual French Communist euphoria in the thirties. -

After Stalin’s death they were put on display in the basement

of the Georgian State Museum in Tbilisi.