|

Hieronymus

Bosch

De Tolnay's (1966) authortative Bosch monograph documents hundreds of paintings attributed to Hieronymus Bosch and most contemporary books and websites still use Tolnay's catalogue raisonée. The catalogue of the 2001 Bosch Exhibiton in Rotterdam lists only 23 original Bosch paintings. Where did all the Bosch's go? In the 1980s the Museum Boymans-van Beuningen in Rotterdam asked Peter Klein, a dendrochronology expert at the University of Hamburg, to date their holdings of Bosch paintings. In the next 20 years Klein analysed all but 2 or 3 Boschs worldwide. The result was a shock to the museums and the art historians : more than half of all panels attributed to Bosch were painted many years after his death. In addition a few of those painted during Bosch's lifetime, like the two "Haywains" were declared copies on stylistic grounds. Fortunately, among the panels that survived the carnage there were some, like the four "Flood" panels in Rotterdam, which were confirmed as painted during his lifetime. They had been in doubt. However, nobody has to my knowledge published a new catalogue raisonnée. - In this essay I used Klein's latest dates (private communication 2005). Klein insists that he can determine only the year in which an oak plank had been cut. To obtain the date it was painted Klein (and I) add a standard 9-year drying time, common in Brabant at Bosch's time and confirmed by one painting ("St. John Evangelist in Patmos") in Bosch's case.

Hieronymus

Bosch, AETATIS SUE 45, 1485, 15 x 12.5 cm, Amherst College,

Amherst, Massachusetts The documented details of Hieronymus Bosch's life, 1450-1516, are quickly told: He was born Jeroen van Aken in s'Hertogenbosch. His father, Antonius van Aken, two uncles, and two brothers were painters working in the Aken family shop, which Jeroen headed after his father's death in 1482. His mother was Aleit van Mynnen. In 1478 Bosch married Aleit van de Mervenne, whose extensive property in s'Hertogenbosch secured his financial independence throughout his working life. By 1500 he was one of the wealthiest men in s'Hertogenbosch, allowing him - for his time - an unusual degree of freedom in selecting his subjects. In 1486 Bosch became a member of the prestigious Confraternity of Our Lady in Hertogenbosch. In 1504 Philip the Fair, Duke of Burgundy and Brabant, ordered a large Last Judgment from Bosch. Bosch died as a financially ruined man. His Confreres of the Brotherhood of Our Lady buried him in an unmarked pauper's grave in August 1516 He dated none of his paintings and only signed a few selected pieces with jheronymus bosch, in large, formal, Gothic letters. His artist's surname Bosch signifies his place of origin which is commonly known as Den Bosch. The same toponym was used by a number of other artists. In the 1980s the Museum Boymans and van Beuningen in Rotterdam asked Paul Klein, a dendrochronology expert at the University of Hamburg to determine the date the wings of Bosch's badly damaged "Flood Triptych" to justify an expensive restauration of the panels. In the course of the next twenty years Klein dated all panel paintings attributed to Bosch. To the dismay of the museums and the Bosch experts more than half turned out to have been painted long after Bosch's death. In addition Klein's scientific method completely upset the stylistically determined order of the existing paintings. Rearranging the surviving paintings according to Klein's dates (P. Klein, private communication 2005) showed that one can "read" Bosch's life from his paintings. This is what I am trying to do in this essay. To my knowlege no complete list arranged according to Klein's dates has appeared so far. Of course, "reading" Bosch's life from his paintings is a haphazard, highly subjective undertaking, which will not find everyone's approval. However, in exchange his work and iconography become greatly demystified. One of the results of this new order is that Bosch must have had - as Fraenger (1975) had already surmised - a learned Jewish mentor, Jacob von Almaengien, who supplied the extensive background knowledge to the "Garden" and the "Temptation of St Anthony" Triptychs. Bosch was a highly imaginative painter, but he could not have had the knowledge of the Neoplatonic philosophy he used in his first painting, nor that of then Hebrew text underlying his last. Jacob von Almaengien was Hieronymus' close, lifelong friend. He appears in a majority of his paintings.

Bosch's

Paintings

A

List

of his Paintings is

One of the earliest Bosch paintings - acording to the art historians a "fragment" of a Last Judgment - was painted on oak planks dendrochronologically dated to 1440, i.e., ten years before Bosch's birth. They were planks his father's shop had acquired on an auction of a defunct workshop. All other Last Judgements by Bosch were painted after 1482 . - I consider this fragmentary painting a "sample" of Bosch's devils and hybrid creatures, which were very popular, to let prospective customers chose "their" devils from.

A

Comment on Bosch as “Le

Faiseur des Diables” Pilgrims charms and amulets from a dump excavated in Den Bosch, [Rotterdam Exhibition 2002]

Temptation

of St. Anthony "St.

Anthony in Central Park" because of the skyscrapers in the

background. In his monograph on Hieronymus Bosch (1977) the

German art historian Carl Linfert in all seriousness declared

this small panel in the Prado to be Bosch's last painting : Bosch

had finally quieted down; his devils had become too harmless to

tempt Sant Anthony's meditations.

The

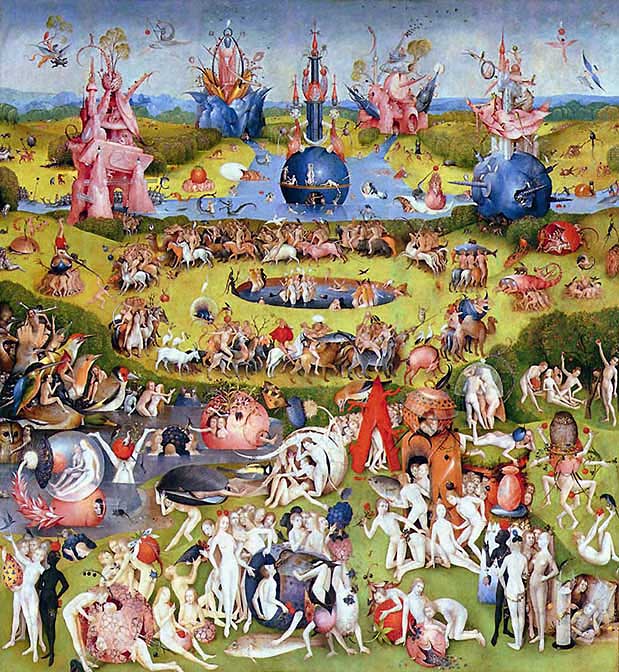

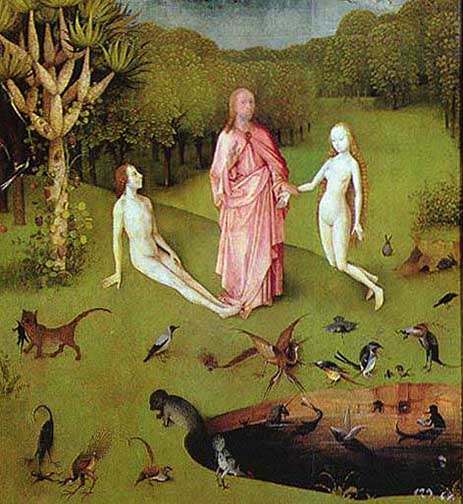

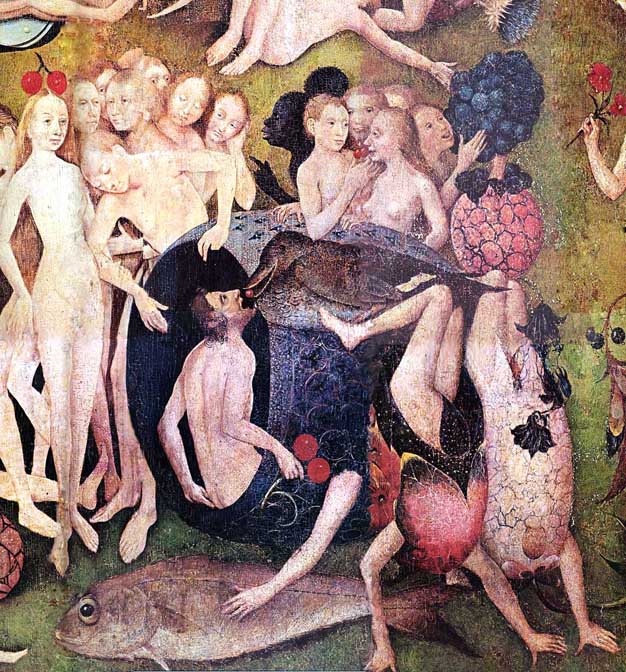

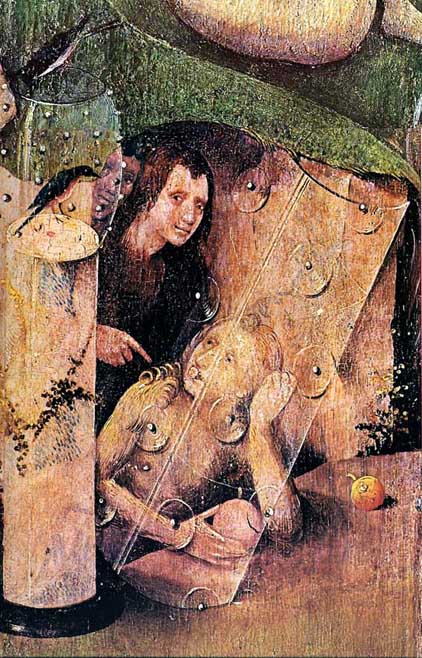

Garden of Earthly Delights

The "Garden of Lusts or Delights" depending on your inclination is Bosch's most celebrated work. It had long been considered his greatest, most mature painting - until Peter Klein showed that its oak planks were cut 1458 and the tripych could have been painted nine years later - i.e. as early as 1467! How could a 17-year-old paint such a deeply mysterious triptych?! The answer, which Fraenger (1975) first expounded, is that he had a mentor, a learned friend who suggested the thematic details and who was Jewish! The alternative would be that Bosch had a Jewish "conversa" for grandmother! - The expensive planks could also have been let to dry another twenty years - to please the art historians. As startling as these suggestions may appear, such cooperation between a learned man and a painter would not be without precedent in Brabant. We have documentary evidence (in the accounts of the Leuven Eucharist Brotherhood) that Dieric Bouts the Elder had two learned, Hebrew-speaking advisors, Professors Jan Varenecker and Aegidius Ballawel, when he painted the Eucharist Triptych in Leuven in during the same decade: 1464-67! - Fraenger later discovered a suitable historical person in Jacob von Almaengien and suggested that he was Bosch's mentor. Closer inspection of the "Garden" triptych shows that Jacob von Almaengien must have been a student of the Neoplatonic philosopher Marsilio Ficino's and a friend of Pico della Mirandola's. The central panel is Bosch's rendition of the Pythagorean Paradise Ficino taught in Florence around 1460. This is the reason why the beautiful people are mere phantoms. They are the souls of the chosen who through Love rise through Ficino's four levels of his Universe, Bosch, however, omitted the fouth, where Ficino places the "graven" image of the Christian God Father(sic!). The physical action in the central panel runs in Hebrew fashion from right to left. The chosen enter through a hidden gate from the hellish place on the right - which is "Our World" This Hell is examined by the “New Man”, of whom Pico della Mirandola in his celebrated “Oratio De Hominis Dignitate" would write (1483): "The Supreme Maker said: 'We have placed you at the center of the world, so that you may observe and consider all that is in the world. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper, mold yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lowest brutish forms of life; but you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine.” The best description of Almaengiens and Bosch's credo. Similarly the left wing does not show the creation of Eve but the establishment of the New Covenant by Christ in the betrothal of Jacob and Sibylle, the sanctification of the happenings in the middle panel. But Bosch disturbes Ficino's universe by a pool of alien creatures below the betrothed and a shimmering, psychodelic death or drug scene in the central panel, both are absent in Ficino's Neoplatonism. The question of who is responsible for these modifications is left to the speculation of the novelist The three authors of the triptych, Jacob von Almaengien, Sibylle, their medium and Jacob's later wife, and young Hieronymus's curly head hide in a cave in the lower right-hand corner of the middle panel. Contemporary German and Dutch art historians deny this exgesis vehemently. This is not the place to argue the evidence. While all interpretations of this triptych are bound to remain speculations, there remains the uncomfortable fact that Bosch painted this most famous - if not necessarily his greatest - triptych in 1467-70, just before he turned 20.

Ecce

Homo This painting, assigned by Klein to 1476, was a commissioned work, possibly painted under the young Bosch's supervision by his father's shop. The sponsors have later been overpainted. This happened frequently with Bosch's lesser paintings. An indication that his fortunes went through several ups and downs. Sometimes he overpainted a painting himself, when a client rejected the commission. He had no compunction in using a painting twice. (e.g. St. John Baptist in the Desert of 1496) In 1478 Bosch married Adeleit van de Mervenne, a local patrician lady who would inherit a large fortune in real estate from her father. This undoubtedly arranged union made Bosch financially independent through out his life - less its last 10 yars. He was a rich man - who died as a pauper. Very unusual for the times, but most important for his oevre : Bosch could paint what he liked, he didn't have to accept commissions with strings attached . After his father died in 1482, Hieronymus took over the family workshop. As he became famous (notorius?) commissions began drifting in. The tedious or undesirable orders he gave to the shop - which explains in part the disturbing uneveness in quality and execution of his oevre.

St.

Hieronymus in Prayer This is a genuine Bosch painting. Hieronymus (St. Jerome) Bosch's name saint in fervent prayer in a luscious "desert". I suggest that Jeroen van Aken (Bosch's baptismal name) painted it at his father's death in 1482.

Last

Judgment Historically 1482 was a year of misfortunes. Not only did Bosch's father die, but Marie von Burgund, the wife of Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg fell from a horse and broke her neck. Maximilian's marriage to Marie had brought Brabant into the Habsburg empire. The rich and powerful burghers of Ghent disliked Maximilian's reign sufficiently that he had to retreat to s'Hertogenbosch to knight Marie's 3-year-old son Philip the Fair and install him as his mother's heir to Brabant. Maximilian's long presence in s'Hertogenbosch resulted in a major commission for Bosch: his first Last Judgement Triptych. Bosch left it to the shop. The dating of its three wings shows that it was worked on for a long time - and it must be one of Bosch's sloppiest paintings. He just wasn't interested in it. However, the triptych has been in the possession of the Hapsburg Archdukes at least since 1502. A document of 1504 in the archives of the Archdukes shows that Bosch was owned a large sum, which, however, seems never to have been paid to him. - It may have been this triptych, which according to Klein took more than 20 years to finish. By the end of 1482 the Ghenter burghers kidnapped young Philip the Fair and kept him as a hostage. Maximilian was powerless to prevent it.

Adoration

of the Magi This commisson by the family Bronchorst and van Boschuyse (coats of arms) caught Bosch's interest to such a degree that he executed at least the central panel himself and - signed it : This Adoration of the Magi is unique in the arts before and after Bosch. It illustrates the apocryphal, non-biblical, Hebrew stories connected with the visit of the Three Magi to Bethlehem. They go back to Adam: Adam had saved Three Precious Things from Paradise: Gold, Incense, and Myrrh, the symbols of his Kingship, his position as High Priest, and of his magical powers of Healing. Noah's sons saved not only Adam's body but also the Three Precious Things. After the Flood they buried Adam's remains on the Hill of Golgatha. The Three Precious Things were brought to Bethlehem by the Magi to anoint the new-born Christ as the King, Priest, and Healer of the New Covenant, as the "New Adam." Christ would, of course, be crucified at Golgatha. At Bosch's time various versions of this story had been translated from the apocryphal Hebrew texts, and a (heretical) Adamite Sect flourished near Brussels. It seems possible that the Bronchorsts were members of it. This

explains the appearance of Adam in the stable door of Bosch's

Adoration. A gleeful, near naked Adam, adorned with all kinds of

highly symbolic paraphenalia, watches the birth of the New Adam.

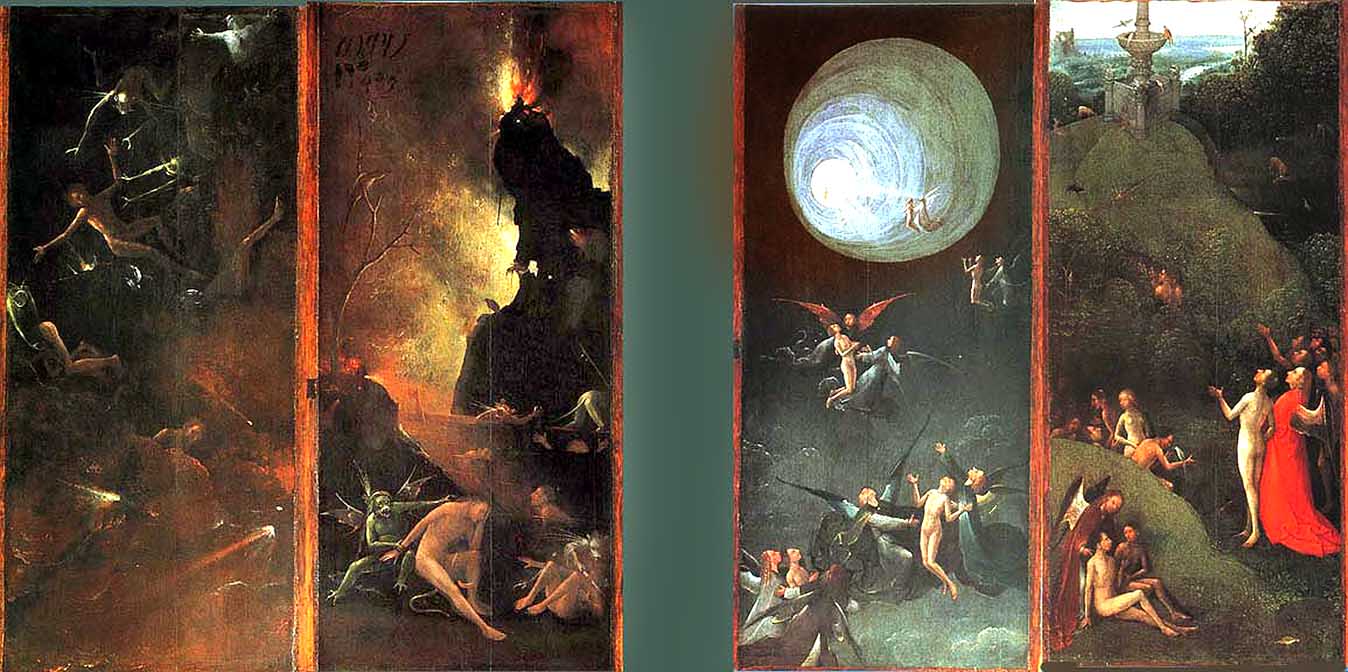

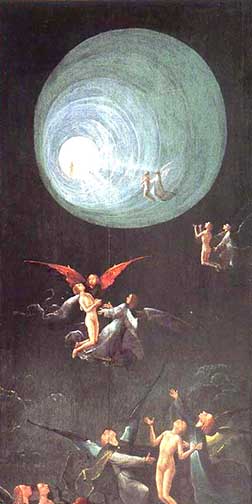

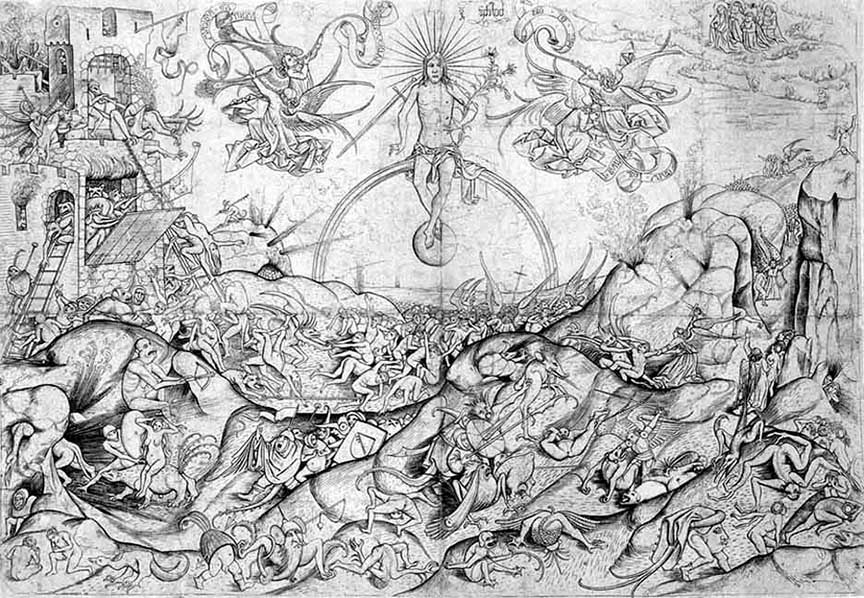

Fragments

of a "Last Judgment" triptych

If the Vienna Last Judgement of 1482 appears like a conventional painting - except for the fashionable Boschian monsters - these four fragments in Venice give an idea of how Bosch himself saw this event: a most unorthodox "transmigration" of the Just to a new life in Christ. This view does not stand alone in Brabantian painting: Dieric Bouts the Elder had painted a similar Two Wings of a Last Judgment in Lille 40 years earlier (~1450). But Bosch's vision has a unique twist to it: Angels transport the just souls through a "sewage" pipe to the Hereafter! Such a vision would not reappear in art until the end of the 20th century, where it is connected to descriptions of shamanic dreams....! There are many other pecularities in both the Bouts and the Bosch triptych : The Descent into Hell wings are conventional but they reside on the right side of the triptych. Both left wings show a man or an angel leading the faithful to the fountain of Life and beyond. The conventional intercessionary role of Church has been dismissed ! The movement in both is anticyclical - "Hebrew" from right to left! “Hell” is on the right, the saved sould ascend on the right-hand side. I believe that a print by Alart Duhameel (1449-1507) in the Kupferstich-Kabinet of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam may depict the central lost panel, of this polyptych. The print adds to, but also elucidates the unorthodoxies of the wings.

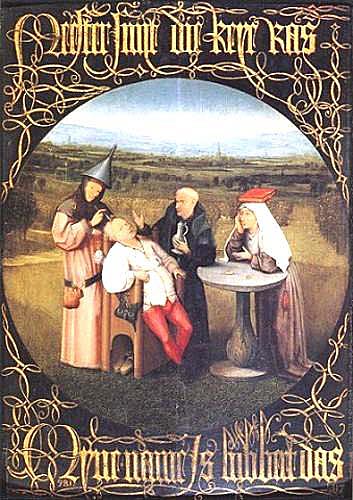

"The

Stone Cutting" In terms of popularity this small panel comes soon after the Garden Triptych. It seems inoccuous except for the strange hats of two of the attendants - which are supposed to indicate that they are quacks. The "doctor" with the inverted funnel seems to perform a brain operation on the patient, to remove the "tumor of folly" (trepanations were already performed during antiquity). However, the Gothic inscription says something relse: "Master, cut the stones out, my name be “Lubbert Das." - das (=Dachs) is the lascivious badger and lubbert means castrated : The folly resides in the testes - and the quack is supposed to cut those out ! There exists a print after Breughel the Elder (1519) which shows a scene at a fair where old women perform several such operations.... - Image from Wilhelm Fraenger (1975)

Triptych

with Three Hermits The subject - the unususal combination of three hermits connected with Christian monasticism - is probably the reason that Bosch painted this triptych himself - and signed it : Two of the three are closely related to his personal name-saints. The painting, now dated to around 1494 - a crucial period in Bosch's life and career - shows his peculiar style : a dark palette, "mystically" overcrowded scenes to the point of being muddled (e.g., The Garden Triptych), and an apparently hasty execution. He worked with highly thinned paints, because they allowed him to work faster. Often the underpainting or layout shows through. This reproduction - digitally enhanced - is from Web Gallery of Art an indispensible resource of excellent reproductions of classical paintings. Don't be mislead, though, by their Bosch assignations and dates. They are based on the pre-1980 literature and are mostly wrong.

The

Wedding at Canaa

There exist several copies of this pivotal panel in Bosch's life - but no original. However, these copies are so similar, that a Bosch original is easily reconstructed. There also exists an earlier drawing by Bosch for the original, which shows several overpaintings - by his own hand? - and clarifies the thematic construction of the painting. On circumstantial evidence I date the original to 1495. It shows a Jewish wedding - albeit with several highly disturbing and decidedly non-Jewish additions: Christ and two Christian canonici attend it, the groom looks like St. John the Evangelist, they serve boar and swan - both forbidden foods - and in the background rises prominently displayed, a "Female Initiation Altar" ! Who is getting married here, and how did Bosch get involved with these people? If one doesn't want to see Bosch's "Jewish" grandmother sitting under the altar, next to the bride, there remains but one plausible explanation : the panel shows the wedding of Jacob von Almaengien with the Sibylle of the Garden Triptych at her parents house. Even the professional critics occasionally admit a similarity between the grooms of the betrothal before Christ in the Garden Triptych and this painting. Or between the groom and St. John Evangelist on Patmos. I have tried elsewhere to weave a possible story connecting these events. Returning to the pecularities of the painting, I suggest that the two learned notables next to Christ are Marsilio Ficino and Albertus Magnus. Two canonical teachers of Jacob von Almaengien. The argument for this lies in a visual comparision with other pictures of the two: Their sitting in front of the golden wall-hanging elevates all three into "virtual" reality. Ficino was still alive in 1495. The most peculiar object, the enigmatic "Female Initiation Altar", cannot be described in simple terms and the reader is refered to op. cit.

The

Pedlar or the

Prodigal Son Klein (private communication 2005) showed that the planks of this tondo (once a rectangular panel) and three minor paintings (Death of the Usurer, Ship of Fools, and Gluttony) were cut from a single tree dendro-dated to 1486/1495. This discovery has led Hartau 2005 to the hypothetical construction of a single triptych, of which the "Prodigal Son" was the outside and the "Wedding at Canaa" the middle panel : If

accepted this would date the Bosch original of the Wedding at

Canaa to 1495. The results of these speculations are presented in op.cit.. The supportive pictorial evidence for such a construction can be derived from Bosch's last Triptych "Sicut Erat in Diebus Noë" Such were the Days of Noah(sic!), commonly also known as "The Great Flood" (1515)

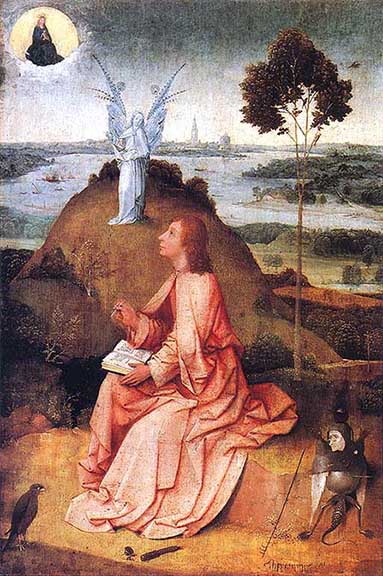

St.

John (Sint Jans!) Evangelist on Patmos

The "proof" that Bosch painted this painting to honour Jacob von Almaengien, recently baptized as Philip van Sin Jans, lies in the features of St. John. This is the same man as in the betrothal of the Garden Triptych, the groom in the wedding at Canaa, and the Prodigal Son. In addition the Brotherhood recorded Jacob's admission at Christmas 1496. Beyond the biographical importance, this panel is the only signed and dated Bosch painting. It was painted 9 years after its dendrochronical date - the single proof for the drying time of Bosch's panels assumed by Klein and myself. The panel has an interesting reverse - which obviously must also have been part of the altar of the Confraternity. A grisaille showing Christ's passion in 6 scenes circling around a pelican feeding his young with its "own blood.”

St.

John Baptist in the Desert The second panel for the altar of the "Confraternity of Our Lady" in s'Hertogenbosch is a retread. It had been painted by Bosch in 1481 as a commission and been rejected by the client. He can still be made out underneath the monstruous black bush with which Bosch overpainted him in 1496.

The

Table of the Seven Deadly Sins This

table at the Prado is a unique piece of furniture which despite

its heretic aura ended in Philip II's personal possession at the

Escorial. A headache for the art historians. Its formal program

is more conventionally Christian than anything Bosch ever

painted: The four Last Things surround a circle of the Deadly

Sins (most ingeniously illustrated). Even the Church has its

traditional role as entry to Heaven. Christ(!) surrounded by

(exactly) 128 rays watches from the center. - There exists no

such table in the liturgical services of the Christian Church.

Sta.

Julia on the Cross Bosch's authorship of the two wings is doubted by some experts. The middle panel is signed in the usual manner - by Bosch himself? The subject matter is not only unique for Bosch but for Northern European art as well. It must have been commissioned by an Italian. Fraenger (1975) devotes a long footnote to the triptych, which exhausts itself largely in a description of the people in the painting.

Adoration

of the Christ Child If

this is a copy of a Bosch original it stylistically appears to

stem from his earlier years. Notwithstanding I date it to 1497

because of the apparent age of Almaengien - whom I believe Joseph

impersonates. If this construct is accepted for the moment, then

the painting shows Sibylle and their child on the 20th

anniversary of the Great Storm Flood of 1477 in which both

drowned.

St.

Christopher This

panel is not signed. The attribution to Bosch rests on the

profusion of symbolic Boschian objects : the jug hanging in the

dead tree, the fish carried by St. Christopher, the various ruins

and monsters in the pastoral landscape.

Christ

Bearing the Cross (Escorial) There exist two "authentic" panels of Christ Bearing the Cross by Bosch from the year 1499, one in the Escorial, the other in Vienna. Neither is signed. Both are an unusual topic for Bosch - and in both show an aged Jacob trying to lighten the heavy weight of the wood on Christ's shoulders. Except to Fraenger (1975) the purported presences of Jacob in the center of these scenes are unimportant or invisible to the Bosch specialist today. To me the paintings express Bosch's increasing anxiety about Jacob, who is still trying to carry Christ's burden on his Jewish shoulders - and is failing.

For

some reason Klein did not date this panel. Was it because the

Vienese Museum feared it would lose another Bosch painting?

Haywain

1 (Escorial)

Both paintings are signed : Copy1 on the left wing, copy 2 on the central panel ! - Klein's datings admit that Bosch could at least have signed both. The triptych appears innocous by comparison with what would follow. The left wing is so conventional that it could have been painted by Bosch's shop, the right wing, assembled from old hell-motives, likewise. The action proceeds from left to right through a central panel - which on closer examination is uncoventional enough to have needed Bosch's personal hand. - The subject is based on the proverbial "Making Money like Hay." Bosch includes Emperor Maximilian I, Pope Alexander VI Borgia, and a "mentally retarded" Philip the Fair among the followers of the money-train to Hell. - But that is as far as he goes in his criticism of the times. Why should he have had the shop make a poor copy in 1504? And why should he have signed that copy on the left, most unintersting panel of a conventional expulsion from Paradise? We can only guess. A tentative explanation is left to the novelist. No art historian who is concerned about his professional reputation will touch this question. Did Bosch paint the triptych in an attack of anger over the unpaid bill Philip owed him for the Vienna Last Judgment triptych? This would be the simplest answer. However any explanation has also to consider the political situation in 1501, the existence of the atrocious Antonius Triptych of 1502 - and Bosch's nemsis, the apostatized Jacob von Almaengien, who unexpectedly appears most prominently for the third time on the outside of this Bosch triptych. It is separated and kept at the Prado.

The

Haywain 2 (Prado) The

second, much more detailed Haywain in the Prado could have been

painted by Bosch himself at the end of 1515. He signed the

central(!) panel. Maybe his brothers had sold the original and

the 1505 shop copy. Maybe Bosch needed some cash badly, and this

painting looked sufficiently innocuous to be a salable piece at

this critical time? - We don't know. Maybe I should remind the reader that copying paintings - the only way in Bosch's time to retain a piece of work - did not have the stigma it has in our days. There exist dozens of copies of Bosch's paintings - he became famous not to say notorious after his death.

Temptation

of St. Anthon Triptych

In 1502 Bosch painted his most acrimonious triptych. According to Fraenger (1975) the triptych is a Hebrew scatology based – like the “Table of the Deadly Sins” - on a visual interpretation of the The Song of Mose, Deuteronomy 32:15 - 33. Every stanza of Mose's harrangue of the Israelites at the time of his death is illustrated by the most daring symbolic images Bosch's mind ever produced. Unless one invokes Jacob von Almaengien as the co-author, it is impossible to understand where Bosch found this obscure Hebrew text, or why he should have painted this triptych. The first translation of Deuteronomy from the Hebrew by Luther would appear only 50 years later. Likewise it is not possible to describe and analyse the three panels in detail here. For a biographical interpretation the reader is refered to op. cit. The central panel describes the misdeeds of the Israelites and the curses Mose lays on them from his deathbed:

”They stirred him to jealousy with strange gods; with abominable practices they provoked him to anger. You were unmindful of the Rock that begot you, and you forgot the God who gave you birth.” [Deuteronomy 32, 16-18] ”They sacrificed to demons which were no gods, to gods they had never known, to new gods that had come in of late, whom your fathers had never dreaded. - For their wine comes from the vines of Sodom, and from the fields of Gomorrah; their grapes are grapes of poison, their clusters are bitter. For their wine is the poison of serpents, and the cruel venom of asps.” [Deuteronomy 32, 20-22] ”They have provoked me with their idols. So I will stir them to jealousy with those who are no people; I will provoke them with a foolish nation.” [Deuteronomy 32. 28] God's punishment will be terrible. - A woman turns into a willow tree, a rider into a thistle, and his horse into a crock spewing sewage. The key to Fraenger's interpretation (1975) is found in the relief images of the broken column of the "Old Covenant" in the middle of the panel. The Israelites have arrived at the border of the Promised Land, which Mose is not permitted to set foot in. Instead of thanking God, they wildly dance in front of the Golden Calf. This lament can only describe Almaengien's Jewish conscience which he thought he could abandon. The outer wings take on the rotten Christian Church. In the right wing a meditating Anthony is oblivious to the sexual travesty next to him - the men holding up the table are castrates, a frog impregnates a virgin in a willow tree. The left wing is more explicit. In the background a prelate enters a pub between the legs of a sodomite, while Antony flies in a sodomite airship across a green-blue sky. - He falls from the height of his dream. Astonishingly, Jacob rescues him and carries the lifeless body across the same bridge, across which Jacob had walked away from the world of the Haywain. Under the bridge the Church sits conniving the pontifical indictment against Jacob and Bosch with a water rat. - On the ice lies Jacob's soul bird, dead, killed by an arrow. Bosch hid the horrors of the triptych behind an elaborate grisaille outside. Hordes of Jews follow ths spectacle of Christ's crucifiction. This

is the only major triptych of Bosch's which Philip II's henchmen

did not confiscate. Long before Philip II invaded the Low Lands

it had been sold - under political pressure? - to Damiaan de

Goes, a Brabantian humanist (1502-1574) and diplomat in royal

Portuguese service.

The

End of Bosch's Painting Career Reading Klein's dendrochronological datings carefully reveals that Bosch ceased to paint after 1505. For ten years after the Antonius Triptych this prolific painter produced nothing - which Philip II had wind of - until in 1515 he painted "Sicut erat in Diebus Noë" also known as "The Great Flood". A year later he died as a ruined man and was buried as a pauper by his Confreres of the Brotherhood of Our Lady in an unmarked grave. What happened? My reading is that Bosch fell from grace after the Table of the Seven Deadly Sins was discovered by the ecclesiastic authorities. The Table served a small group of men who regularily gathered in secret around Jacob to study apocryphal Hebrew texts. The inquisition was quietly hunting down Jewish renegades, and Jacob was known to have deserted his baptismal Christian faith. At first nothing happened. Bosch was an excentric but rich and respected pillar of society. Maybe he was warned of his association with Jacob who enjoyed no such protection. This slow surreptious nagging of the inquision - and a financial argument with Philip the Fair, who had just been elected King of Spain - resulted in the "Haywain Triptych". As the noose tightened Jacob was plunged into a deep crisis with his Jewish heritage. Christ had proven powerless in removing this ancient burden of the Tribe of Jacob. He asked Bosch to help him overcome the curse of Mose. Together they designed the "Anthony Triptych". As the situation grew more dangerous Bosch had the Haywain copied in the shop and got rid of the original. However, the much more dangerous "Antoniy Triptych" he hid with a local sympathizer - who eventually sold it to Damiaan de Goes. In my story Bosch took Jacob on a pilgrimage to Santiago and Portugal in the hope to restore his mental anguish. There they found themselves drawn into the exodus of the Jews fromPortugal and Spain. Jacob died among his tribe on the boat back to Amsterdam. In Bosch's absence the shop went broke. To save herself his wife separated her inherited property from her husband. Bosch, upon his return, found himself a finacially ruined man. His brothers had even sold the copy of the Haywain. This may have happend in 1512 or 1514. Of course, this is all a fictitious sequence of events, there are no direct pieces of evidence, except a report about his sister collecting his last belongings, and a document of Hieronymus Bosch's death and burial paid for by the Confraternity.

Sicut

Erat in Diebus Noë

Briefly, according to Fraenger (1975) the left panels show scenes of Jacob's and Sibylle's life around 1476, the right two show the Nephilim, (Genesis 6, 1-8), the diabolic offspring of the fallen angels, who subsequently drowned in the Biblical Flood. The middle panel is missing. According to Carel van Mander it showed the exodus of the Portuguese Jews from Oporto, around 1507 ! I see this last painting of Bosch as a memorial for Jacob van Almaengien after his death in Portugal. The scenes show Jacob on his knees praying for the rescue of Sibylle from a fire at her father's house, being robbed and beaten by local "Nephelim" in Den Bosch, and finally receiving new clothes from an angel, which leads Jacob to a Saulus-Paulus-like vision of Christ and his conversion. - Sicut erat in Diebus Noë. The fourth panel shows the world after the flood. Jacob kneeling by a dead woman - Sibylle with their child - ties the painting to the Great Flood of 1477 in which Jacob's wife and child drowned. - The readings are Fraenger's (1975). Helped by Klein's dating, I only connected them to the overall biography of Bosch's life. Most of my stories describing Bosch's and Jacobs's life derive from this polyptych. The four panels were discovered in 1927 by a Dutch art dealer in the collection of the Marquis Chiloëdes in Madrid. They are now in the Rotterdam Museum, which, faced with the expense of their badly needed restoration, initiated Peter Klein's dendro-analysis of Bosch's work. The images were scanned from J. Koldeweij et al (2001), the catalogue of the Bosch Exhibition at the Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 2001.

|