|

The

Life and Times of |

Table of Contents

1.

Jacob's first visit to s'Hertogenbosch, Jeroen paints

Terra Nostra, 1467-1468

2. Jacob returns, Jeroen

paints the Garden Triptych, 1468-1470

3. Sibylle

and Jacob's Wedding, They leave for Antwerp, The Storm flood,

1472-1477

4. Jeroen marries Aleit, His Father

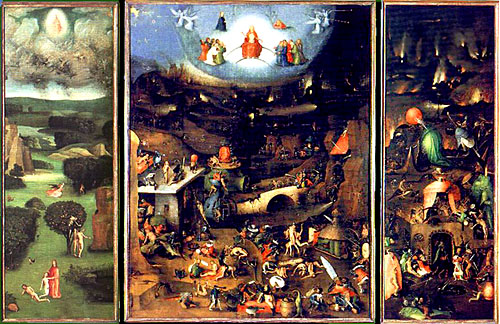

dies, Bronchorst Epiphany, Last Judgment, 1478-1492

5. Jacob

returns, Jacob's Baptism and admittance to The Botherhood of Our

Lady, 1494-1496

6. The Table of the Seven Deadly

Sins,The Temptation of St. Anthony, 1497-1502

7. Disaster

Strikes, The Haywain, Jacob persued by the Archbischop of Colologne,

1502-1504

8. Jeroen takes Jacob to Spain and

Portugal, Jacob dies on the ship home, 1505-1506

9. Jeroen

returns to bankrupt shop, Sicut Erat in Diebus Noë, He dies a

pauper, 1507-1516.

10. Notes to the unwary

Reader

Bosch's

Paintings

1.

Pilgrim's Badges excavated in Den Bosch, 15th cent,

Rotterdam

2. Fragment of a Last Judgment,

1466, Munich

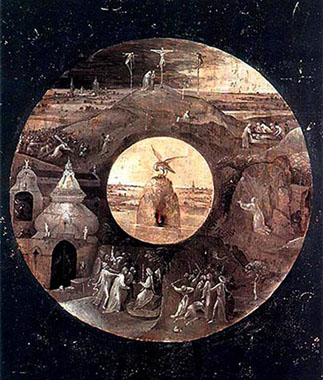

3. Temptation of St. Anthony,

1466, Madrid

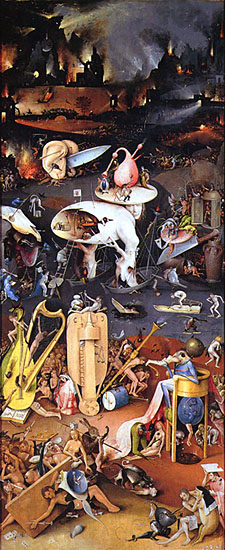

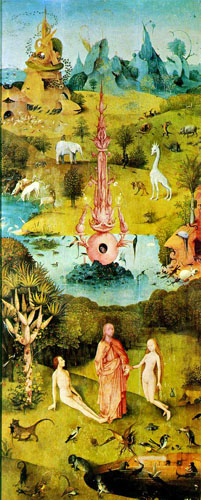

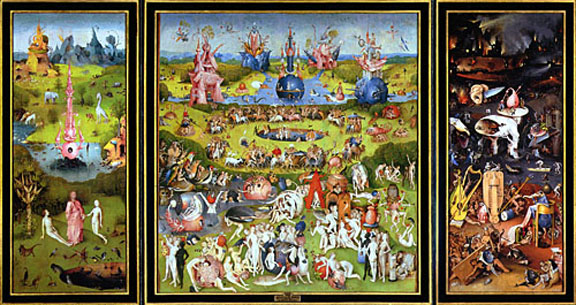

4. Garden Triptych, Right Wing,

the Burning City, 1467, Madrid

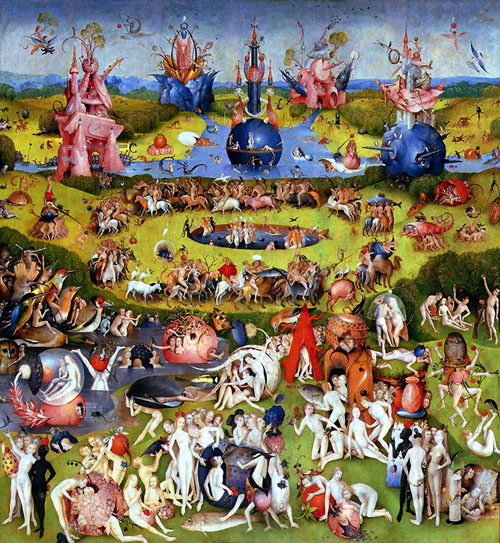

5. Garden

Triptych, Right Wing, the Tree Man, 1467, Madrid

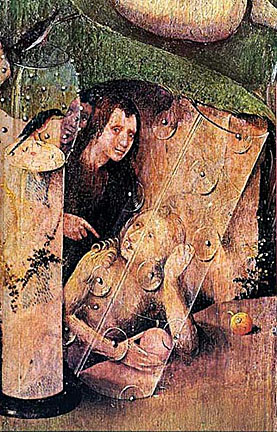

6. Garden

Triptych, Right Wing, Musical Instruments, 1467, Madrid

7.

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, the Emperor Bird, 1467,

Madrid

8. Wedding at Canaa, Female Initiation

Altar, copy 1568 (original 1476), Cologne

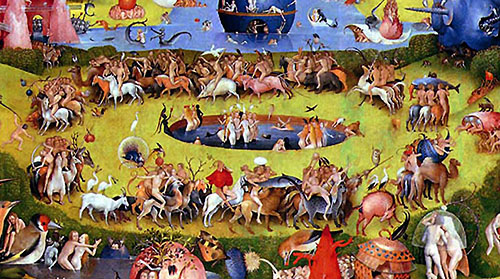

9. Garden

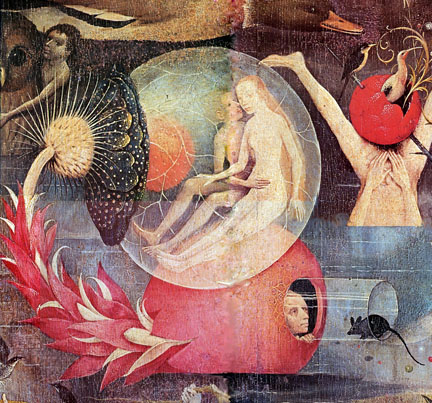

Triptych, Right Wing, Terra Nostra, 1468

10. Garden

Triptych, Central Panel, Wedding Cavalcade, 1468, Madrid

11.

Garden Triptych, Central Panel, Sibylle and Death in

Paradise, 1468, Madrid

12. Garden Triptych,

Central Panel, Love and Death in Paradies, 1468, Madrid

13.

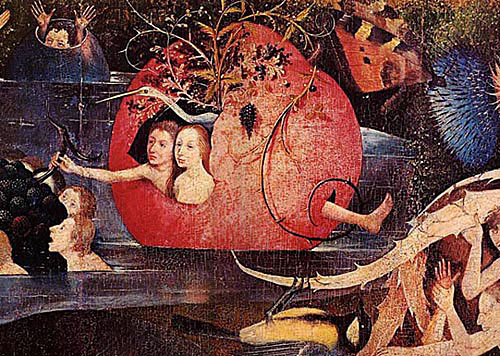

Garden Triptych, Central Panel, Loving Couple in a

Pomegranate, 1468, Madrid

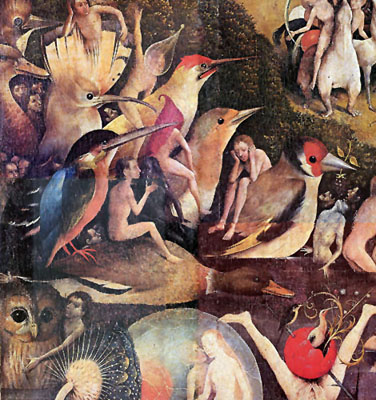

14. Garden

Triptych, Central Panel, The Hoopoe and the Persian Birds, 1468,

Madrid

15. Garden Triptych, Central Panel,

Jeroen and Sibylle, 1468, Madrid

16. Garden

Triptych, Central Panel, The Cave, Jacob, Sibylle, and Jeroen 1468,

Madrid

17. Garden Triptych, Central Panel,

The Paradise,1468, Madrid

18. Garden

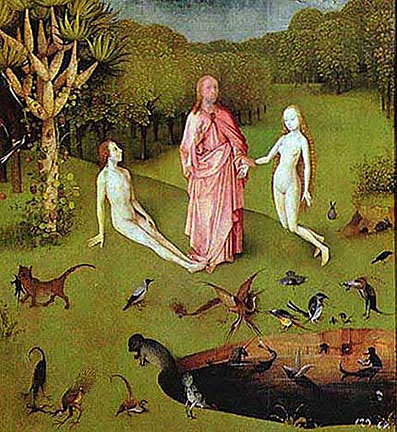

Triptych, Left Panel, Creation of the New Covenant,1469, Madrid

19.

Garden Triptych, Left Panel, Betrothal of Jacob and

Sibylle,1469, Madrid

20. Garden Triptych,

1470, Madrid

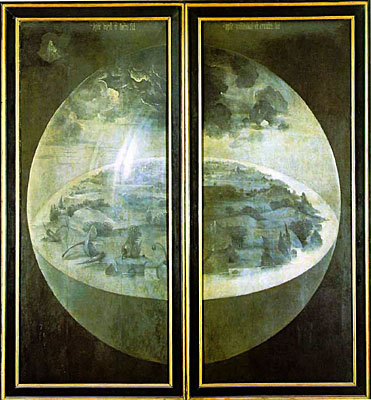

21. Garden Triptych, Outside,

Third Day of Creation, 1470, Madrid

22. Wedding

at Canaa, copy 1570 (original 1475), Rotterdam

23. Wedding

at Canaa, Christ, Ficino-Albertus Magnus, 1570 (original 1475),

Rotterdam

24.

Wedding at Canaa, Jacob, Sibylle, Female Altar, 1570

(original 1475), Rotterdam

25. Wedding at

Canaa, Drawing after Bosch painting, Louvre, 16th cent

26. St.

Hieronymus in Prayer, 1482, Ghent

27. The

Second Coming of Christ, 1482-1496, Vienna

28. The

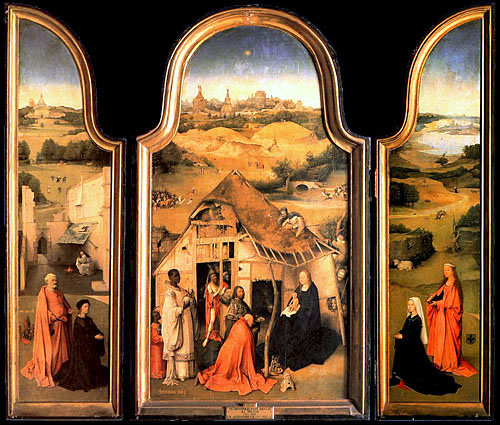

Bronchorst Epiphany, 1485, Madrid

29. The

Bronchorst Epiphany, Adam 1485, Madrid

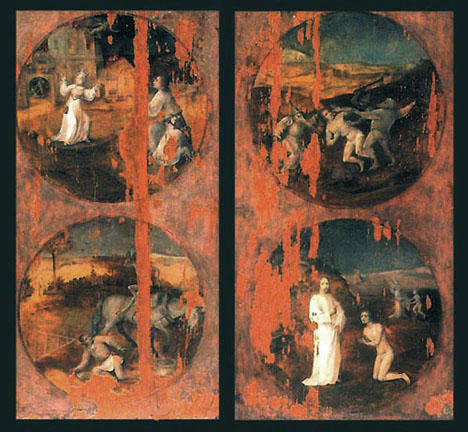

30. Four

Wings of Christ's Second Coming, 1492, Venice

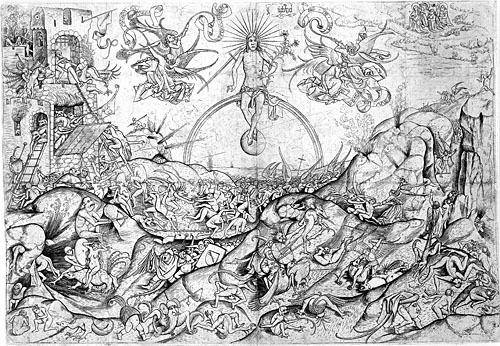

31. Allard

Duhameel, Engraving of a Last Judgment after Bosch, 15th cent,

Amsterdam

32. The Prodigal Son, 1495,

Rotterdam

33. St.

John the Evangelist on Patmos, 1496, Berlin

34.

St.

John the Evangelist on Patmos, Reverse: Christ's Passion, 1496,

Berlin

35.

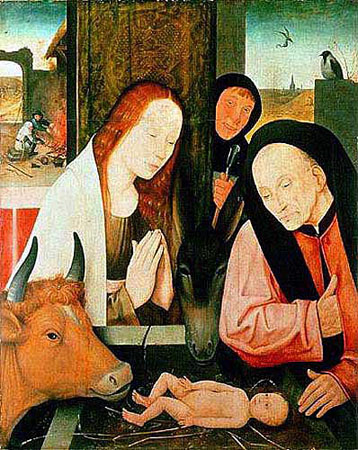

Adoration of the Christ Child, copy 1568, (original

1496), Cologne

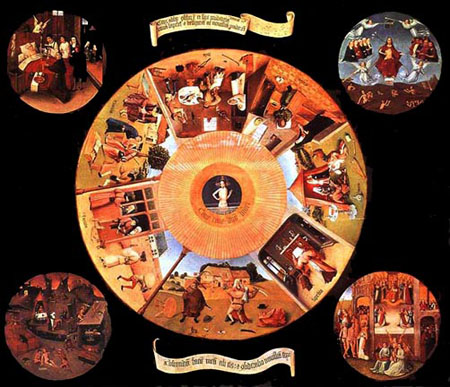

36. The Table of the Seven

Deadly Sins, 1498, Madrid

37. Christ Bearing

the Coss, 1499, Escorial

38. St Christopher

carrying the Christ Child, 1497, Rotterdam

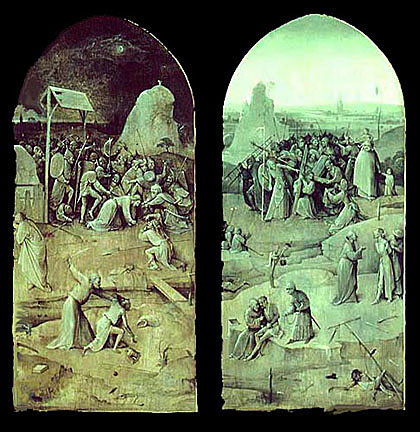

39. Temptation

of St.Anthony, Outside, 1502, Lisbon

40. Temptation

of St.Anthony, Middle Panel, 1502, Lisbon

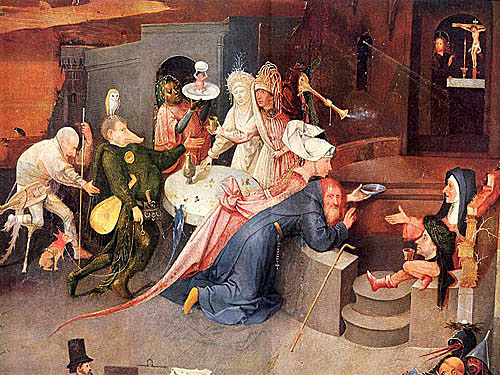

41. Temptation

of St.Anthony, Middle Panel, St. Anthony, Black Mass, 1502,

Lisbon

42. Temptation

of St. Anthony, Middle Panel, Duck-Ship, 1502, Lisbon

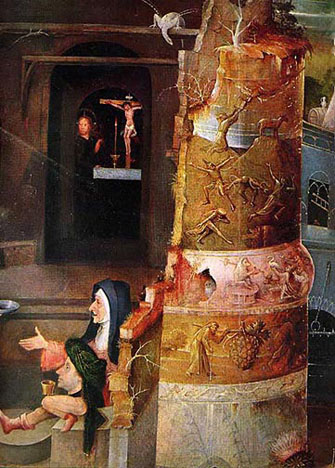

43.

Temptation of St.Anthony, Middle Panel, Broken

Column of Deuteronomy, 1502, Lisbon

44. Temptation

of St.Anthony, Middle Panel, Army of Enemies, 1502, Lisbon

45.

Temptation of St.Anthony, Middle Panel, Stricken

People, 1502, Lisbon

46. Temptation of

St.Anthony, Right Wing, St. Anthony in the Desert, 1502, Lisbon

47.

Temptation of St.Anthony, Right Wing, St. Anthony

among the Travestites, 1502, Lisbon

48. Temptation

of St.Anthony, Left Wing, St. Anthony's Fall from Grace, 1502,

Lisbon

49. Temptation of St.Anthony, Left

Wing, St. Anthony flying,Sodomite Airship, 1502, Lisbon

50.

Temptation of St.Anthony, Left Wing, Papal Bulle,

St. Anthony's Rescue, 1502, Lisbon

51. The

Haywain, Middle Panel, copy 1516, (original 1504), Madrid

52.

The Haywain, Outside of Triptych, Jacob on

Pilgrimage, 1516, (original 1504), Madrid

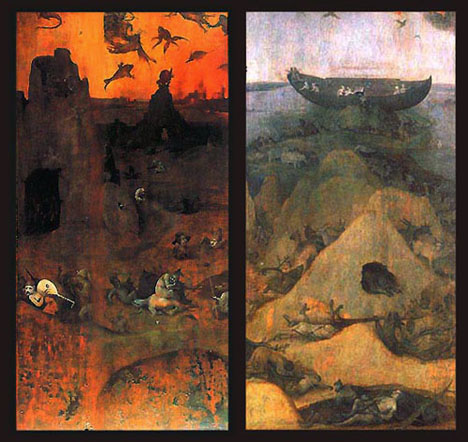

53. Sicut

Erat in Diebus Noë, Sibylle's Rescue, Jacob's Conversion, 1415,

Rotterdam

54. Sicut Erat in Diebus Noë,

The Nephilim, Noah's Ark, 1415, Rotterdam

55. Sicut

Erat in Diebus Noë, Sibylle and her Child, 1415, Rotterdam

The cover uses a little-know painting: Portrait of Hieronymus Bosch at the age of 45, mid 16th cent, Amherst College, Mass, scanned from the catalogue of the Rotterdam Bosch Exhibition, 2001. All other reproductions are from the author's collection.

On a late September day in 1467 Jacob wandered among the booths of the Michaelis Fair in s'Hertogenbosch. A good-looking, tall man with a prominent nose, a sensuous mouth. and intelligent dark eyes below a two-part receding hairline. Jacob was well-dressed for a semi-itinerant magister of philosophy, astrology, and mathematics. He had arrived in Brabant as one of the tutors of the eight-year-old Maximilian of Hapsburg.

Maximilian had been sent by his father Friedrich III, Archduke of Austria and Roman Emperor, as an emissary to attend the inauguration of Charles the Bold as Duke of Brabant. But the true purpose of Maximilian's journey was for him to make the acquaintance of ten-year-old Marie of Burgundy, the heiress to Charles the Bold's possessions in Brabant, the Low Countries, and Burgundy. A delicate political mission which offered the promise to greatly increase the realm of the Hapsburg dynasty.

Jacob had much free time to explore s'Hertogenbosch. One reception followed the other, at which he was not needed. They were roasting three oxen in the town square, which together with an abundance of wine the influential citizens of the city had presented to Duke Charles. The common folks crowded the fair in a meadow extra-muras of town. Jacob liked what he saw, the people, their bucolic dances, and their refreshing spirit. Innsbruck, where he had spent most of the year with Maximilian, was a small, sedate town trapped between mountains. Before his appointment to the Emperors court he had lived several years at Galeazzo Sforza's court in Milan and in Florence at the feet of Marsilio Ficino, at Cosimo di Medici's famous Neoplatonic Academy. Italy was ruled by autocrats and the all-pervasive Church. By comparison Brabant was a wide open country inhabited by unruly people. The power lay in the hands of the wealthy merchants, of its rich cities, and a few landowners. Their Burgundian Dukes lived far away. The simple people stood on two legs, always ready to defend their independence. They were strong-willed and obstinate, a trait which was missing among the commoners of Austria and Italy. There was an openness to revolutionary, often heretical ideas here, which the Church suppressed further south.

Jacob was Jewish. Although he did not practice his religion, the Christian Church was anathema to him. A mind-set he had learned to hide. He had been born in the German Rhineland, which had earned him the surname van Almaengien. He had left his town and the narrowness of its community early in exchange for a life as an independent wanderer through the learned cities of Europe.

There were dozens of stands on the fair grounds, temporary tents and scaffolding. Anything was being sold from trinkets, to kitchen utensils, earthenware, bread, vegetables, and precious cloth. In its central square, surrounded by eateries and wine merchants, they were dancing to a simple band of fiddles, drums and pipes. A chaotic, burlesque scene. He walked down a narrow lane in which fortune tellers, vendors of herbal medicines, and dentist practiced their trades. At the end of the lane ladies of easy virtue beckoned to the "feine Herr." The lane opened into a meadow, where in a guest-house a troop of prostitutes from Amsterdam had taken up residence for the occasion. The wings of a windmill turned on a neighboring hill.

He turned into a neighboring lane and found himself in front of two booths. A sign on the first said "Jeroen van Aken – Schildereij,"---paintings. In the other sat a young, red-blond woman with her back to him. The sign on her stall announced "Sibylle - Palm Reader - Pilgrim's Badges." Sibylle and the young Jeroen, a man of about eighteen with curly hair, broad lips, and a tanned complexion, were absorbed in an intense conversation. Sibylle gesticulated with her hands to make a point to Jeroen, who every now and then broke out in hearty laughter. Although he saw her only from the back, her graceful, lively gestures and her intensity intrigued him. She radiated a power, which he could not explain. He watched them for a while. Absorbed as they were with each other, they did not notice him.

Suddenly Sibylle turned and stared at him. For a few seconds she said nothing, then got up, made a deep curtsey before him, and to his surprise addressed him in Hebrew, "My Lord, are you the Messiah who will deliver us from this vale of tears? I offer you my life."

Jacob stared at her in bewilderment. Her ageless face, her eyes! He courtly extended his hand to raise her. She examined his hand, but said nothing. "How did you guess that I speak Hebrew?" he asked perplexed. She looked at him and their eyes met, full of intense questions.

Jeroen's laughter broke the spell. "I didn't understand what she said to you," said Jeroen innocently. "Sibylle often has attacks of clairvoyance. She sees things, we cannot see. Sir, don't be offended by her words. She means no harm. Come sit with us." Jeroen went into the back of his stall to get a stool for Jacob.

Avoiding her eyes Jacob said embarrassed "I am no Messiah," and added with annoyance in his voice, "What a preposterous idea." Sibylle did not respond. She sat on her stool staring at him, mute. Jeroen took over. "She is exhausted from seeing you," he said. "Sir, look at her trinkets."

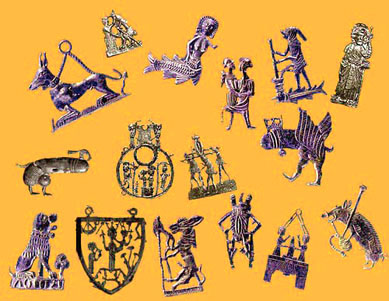

Pilgrim's Badges excavated in Den Bosch, 15th cent, Rotterdam

He pointed at Sibylle's table. It was strewn with pewter amulets, a Madonna in a mandorla, Christ with thorns, various saints, a witch riding a broom, and an assortment of profane objects, a penis with wings and feet, a couple copulating, a vulva carried in state by three penises. Jeroen explained, "The pilgrims who come to the fair buy these amulets. They are very fashionable. I design them, and she has them cast from wooden molds."

Jacob listened absentmindedly, the silent woman disturbed him. What else did she know? Where was she from? He felt a confused attraction to her. "Let me show you my schilderen," said Jeroen. They got up and walked into his stall. Being out of reach of Sibylle's intense gaze helped.

Fragment of a "Last Judgment", 1466, Munich

In the back of his booth Jeroen kept a large panel. On a dark background he had painted a motley collection of suffering people with such realism as Jacob had never seen before. A naked woman standing in the black lava issuing from a fire-spewing volcano watching over an emaciated man trying to rise from the ground. A king or pope crowned with a tiara but without clothes wringing his hands in agony. People drowning, writhing, dying. In the center of the panel colorful hybrid creatures, half insect, half bird attacked more naked people. One animal half rat, half bird dragged a woman upside down across rocky terrain. On the far right an old witch hovered under the fire rain of another volcano....

A chill crept over Jacob's back. How far he had ventured from sunny Italy, from its restrained formal beauty! No Italian would paint this "vale of tears" as drastically or as horrifyingly as this young man. The passions under the surface of these Brabantian Northerners were frightening. He asked Jeroen, what this painting was. Jeroen shrugged, "A pattern sheet, an example of my abilities. From it people can chose their own hell or just order a painting of one of those creatures for their private use. I am known as the faiseur des diables to the French speaking-people from Flanders, who like this kind of excitement."

Compared to Jeroen's the beasts of the apocalypse seemed harmless. Jacob asked where he had seen these creatures. Jeroen said light-heartedly, "In my dreams at times. Some, however, are the inventions of Sibylle. To imitate the creatures she sees in her visions, she will beat her arms, make a rat face and screech like an owl. Then I see such a mixed animal in my imagination, and when the Guelders devastate the country one can see any number of mutilated people dying. Sibylle also has visions of great fires and is much afraid of them. The world can be a horrifying place."

Sibylle had recovered, and asked Jacob to chose one of her trinkets. He could not have said why he selected the thorn-crowned Christ. When he pulled out his money, she insisted on making the pendant a present to him. "If you are not the Savior," she said enigmatically, "Christ is the Messiah."

For the remainder of the day Sibylle's haunting face and Jeroen's strange creatures befuddled Jacob's mind.

Maximilian's mission was going well, and it was decided to stay longer in Hertogenbosch. Jacob was content. Occasionally he had to attend Maximilian's meetings with Marie and her ladies-in-waiting. It was Jacob's obligation to show-off the intelligence of his student to the Burgundians. Maximilian was bright, quick in comprehension, and had an excellent memory. It was a pleasure to work with him. At the same time he was unusually self-confident for his age, without arrogance. One day Jacob made the two youngsters play mathematical games with a magic square. At another Maximilian recited the neoplatonic teachings of Ficino by heart. The great success came when Jacob had carefully rehearsed him in the complete horoscope of Marie. The courtiers of both parties were utterly astonished. They had to perform this show twice. At the second time Maximilian added his own illustrious horoscope and showed how, by the constellation of their natal planets, Marie and he were practically destined for each other.

However, Jacob's mind was preoccupied with the Brabantian Sibyl and the imaginative talents of Jeroen the painter. One afternoon he slipped away and walked out to the tent city of the Fair. To his disappointment, Sibylle was not there, but Jeroen received him with a show of pleasure and a measure of ironic amusement. "Your friend is supervising the casting of more badges. She sold most of the ones you saw," he said tilting his curly head. "She has been talking about you ever since she met you. I cannot tell why she is attracted by you, maybe because you are Jewish like she is, maybe just because you are an elegantly dressed foreigner"

Jacob took the opportunity to learn more about her. Jeroen described how they had known each other since early childhood. She lived in Vught, a village a mile away on the other side of the river Dommel. His grandmother had also lived in Vught. There was a small Jewish community there. "Oh well," he said. "Sibylle was my first sweetheart, and her visions have held me captive to this very day. She knows more than you can imagine, all learned from her grandmother. Her grandparents fled to Vught from Provence in Southern France." He laughed. "I guess, there were more heretics in Provence than good Christians."

Jeroen looked inquisitively at Jacob. Maybe he shouldn't say such dangerous things, he hardly knew Jacob. He hated the Church and its corrupt clergy, and yet the Church had been a very generous client to his father and brothers, all painters. He said, "After the great fire five years ago we painted several triptychs for the burnt-out monasteries and for city hall. All religious subjects. I should not revile the hands who feed us, but I can no longer see pictures of fat priors sitting in pomp before a sweet Mother Mary."

Jacob asked, "Your grandmother in Vught is not Jewish, is she?" Jeroen blinked. "You mean, because I am against Christian institutions? -- She is dead, and we don't talk about such things at home. She went to church, but that doesn't mean much. She was an old woman, when I knew her." Jeroen, suddenly pensive, said, "However, this would be a good explanation, Grandmother van Aken, a converted Jewess?" He shook his head and continued, "I have always attributed my un-Christian state of mind to the influence of Sibylle, she is two years older than I. But I also dislike Jews, certain dishonest Jews."

Jacob smiled sadly, some of the worst Jew-haters were Jews who had broken with their religion. Jeroen's face brightened. "You are right. Sibylle's father is such a Jew. He buys and sells 'antiques' and lends money to the local landowners and merchants. At her house they celebrate the Jewish holidays in Hebrew, but to prove his modern independence her father eats pork, and they never attend Jewish services. But nobody in that house is baptized. Her mother died at Sibylle's birth. Her stepmother brought her up. After the death of his wife her father turned into a pompous man. This is why Sibylle is searching for the Messiah and gave you this Christ-with-thorns pendant. She believes that Christ is the Messiah. I have kept her from getting herself baptized in Church."

Jacob turned these news over in his mind. He had stumbled into a complicated family tangle. He was not a medical healer as many of the scholars were whom he had met. He enjoyed teaching young people, but he knew enough about the mind and soul to guess that Sibylle's precariously hypersensitive imagination was connected with the chaotic religious situation at her home.

Jeroen interrupted his thoughts. "But who are you?" he asked bluntly. "I have heard in town that you are the tutor of young Maximilian. Are you a scholar then? Your dress and behavior is not that of one of the rich and powerful. They don't come here." Jacob, seeing that Jeroen's question was more than justified, briefly told him his story. "Sibylle thought me a wandering missionary or even a prophet," he added recalling his shock at her Hebrew pronouncement. "I have no religious message or want to reform the world. I think much like you do. The people I come in contact with, although they are often nominal priests like my teacher Ficino, are open-minded. They pay lip-service to the Church, but we occasionally discuss the failings of Christianity. Ficino considers the Greek philosophers to be his great models."

The idea occurred to Jacob to find out what Jeroen knew of Italian Renaissance painting. As it turned out, Jeroen had seen some contemporary paintings which had been brought back by rich Brabantian merchants from Italy. "Their application of paint is very clever and formal," Jeroen said, "but they don't expose the troubles we have here, the brutality of the wars, the suffering of our people, the deplorable state of our Church and governors." He finally said emphatically, "Their way of seeing and painting doesn't suit me." Jacob told him of his astonishment at his free and scathing handling of the human body. Jeroen laughed. "But that is what man looks like and what some of us see. Why should I brighten up reality?" "No," said Jacob, "I mean that you paint people like that. In Italy and Germany that is difficult to do. Naked people are still relegated to mythological or approved religious themes or have to be established saints, like St. Anthony, according to Athanasius he had visions like yours." Jeroen pulled a face. "Saint Antonius is not my lucky subject. I'll show you."

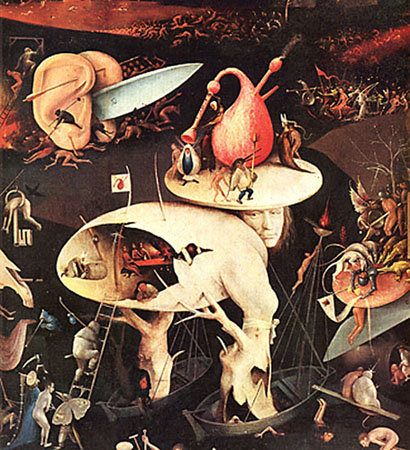

Temptation of St. Anthony, 1466, Madrid

From the recess of the booth he brought a modestly sized panel, a contemplative St. Anthony sitting in a tree stump by a brook. A number of grotesque but rather harmless monsters were threatening the hermit. Between trees a city of white, tall buildings was visible in the background. "The New Jerusalem," said Jeroen. The painting appeared flat and unimaginative compared to his "pattern-sheet." Jeroen said, "This Anthony was a commission, which I painted two years ago. The client rejected it. He felt, the saint was too well-fed. I am now trying to sell it to some enthusiast. I have been told that nobody has ever painted Anthony's visions." Jacob asked whether such a rejection was not a sizable financial loss. Jeroen told him that it was painted on some old planks his father had bought at an auction of a bankrupt painter's shop. Jacob was right, competition for commissions was fierce. Jeroen returned to Jacob's earlier question. "But there is one painter in Leuven, Dieric Bouts, who paints Hell like I see it. He also has an unusual vision of the Last Judgment. The good people go straight to heaven without the help of the Church. That is what I sometimes hope for. I admire Bouts." Jacob had not heard of Bouts. He was impressed by Jeroen's directness and by his uncompromising opinions. He would make an exceptional student.

Sibylle appeared with a young man carrying a basket holding the day's production of amulets. She seemed a different person. Her eyes sparkled when she saw him, "Here you are! I shouldn't tell you, that I have been thinking of you all these days. I am happy to see you and that you haven't forgotten us." Jacob felt that, if Jeroen had not been present, he would have embrace the vibrant figure. Awkwardly he attempted to help take the heavy burden from the man's shoulders. "No," she said cheerfully, "the badges are too fragile." The man carefully backed the basket on top of her table and slipped out of its straps. Together the three unwrapped the amulets. Among them was a new, more complicated casting. A large circle enclosing a naked man with a crown and an ornately dressed woman. Between them in a rectangular box stood an angel protecting a young boy. The contraption was topped by a man and a tiger holding up what looked like a shirt. Jacob looked at it in puzzlement. She laughed. "The knight is you, he has a sword in his hand. The lady is I, and in the center stands Jeroen protected by his guardian angel." Jacob blushed and asked, "But whose shirt are the two figures on top holding up?" She winked at him. "That is the Golden Fleece. The amulet is really supposed to show Jason and Medea and her brother being led to sleep. But today I saw us three in it."

Watching her nimble hands arrange her wares in careful patterns, Jacob mused about this allegory. Now she saw him stealing the Golden Fleece with her! He felt tempted to purchase this second prophecy, but restrained himself. Don't fan the flames! Her soul was afire, not to mention his own.

As if she had read his thoughts, she began in an agitated voice relating a dream of a few nights ago. A great conflagration. A city burning, smoke and fire billowing from the houses, people with hooks precariously balancing on ladders trying to tear down burning timbers. The sky all red. A burning windmill. Across a bridge over a river an army marched behind an armored knight on an old horse led on by a half-crazed footman. Naked people were jumping into the river to escape the heat, only to drown. Sibylle looked at Jacob, "You appeared in my dream and said that they were Spaniards devastating the Low Countries." She said. "If you had called them Guelders or Frenchmen, but Spaniards?" She shook her head. "I woke. Fires frighten me."

Jeroen had got a piece of paper and in rapid strokes drew a sketch of her dream. His houses were tall. He had added birds fleeing from the flames and people running from the city through a burning gate tower. They stood around him watching the drawing grow. Sibylle offered some additional detail, a single tree by the river and a sailboat on a lake at the foot of the city where more people were drowning. Jacob watched him draw this frightening scene. Full of admiration Jacob asked, "Now you will convert the drawing into a painting? I already see the red sky, the white heat, and the black smoke." Jeroen nodded. "She is going to dream up other parts of Our World." He said excited. "Terra Nostra will be a large panel and take me a couple of months."

Jacob visited them a last time before Maximilian's court moved on to Dijon, the Burgundian capital. Sibylle had invaded his dreams. She was around him all the time. On the one hand he pondered what could be done to stabilize her dangerously virulent mind, on the other he knew that it was her visions that attracted him. His consciousness reminded him of Jeroen, who had been her companion for many years. She would probably endow him with the power to separate her from Jeroen. What could he do to keep the friendship between the three of them in balance? Should he try to remove Sibylle from her miserable family and take her with him? So far this loomed like a large unresolved responsibility in his mind. He smiled at himself: Jacob the Savior!

Jacob found them both in their booths. Jeroen had made several new drawings for his envisioned painting. Most eager to hear Jacob's opinion, he laid the sketches out on the counter of his stall. To Jacob they were as strange as the large panel of model monsters, but the details of the drawings were precisely controlled and highly evocative.

Two oversized ears cut apart by a large butcher knife and speared together by an arrow. Jacob noticed that the knife's edge was chipped. "Yes," said Jeroen, "we once threatened each other with a knife in an argument over 'hear who has ears,' When I threw the knife at Sibylle, it hit the ground and got chipped." He opened a drawer and pulled out the knife. Sibylle covered her eyes with her hands. "His neighbor, a knife-smith, makes them." Inside the ear Jacob discovered a small black figure with a lance. "The devil," explained Jeroen, "who makes our ears ring and arouses our passions."

He pulled out a large sheet with a tree-man. Two ghostly withered willow trunks as legs supported the body of the man: a hollow egg-shaped deformity, broken open. Inside of this belly Jacob noticed five comrades tippling the wine an old woman drew from a barrel. However, most disturbing, this unnatural figure had a head with a highly intelligent face looking critically at the observer. The head of the tree-man was covered by a circular disk on which all kind of people danced around an enormous bagpipe. The feet of the grotesque creature were two derelict boats stuck in a frozen lake, where naked skaters drew circles.

"This drawing is an old dream of mine," Sibylle said, "from the days of the knife quarrel. Only in the last weeks have I understood its meaning. The frozen lake represents our frozen consciousness. The body of the tree-man is lifeless and rotting. His belly is inhabited by five intoxicated good-for-nothings: our five senses. On his hat a couple is being mislead by desire and debauchery, turning round and round to the frivolous tune of an obscene bag-pipe." She looked straight at Jacob, and said, "and the Face observing Our World from the center of the painting you know."

"Yes," said Jacob, narrowly evading her allusion. "He is the New Man. Pico, a friend and co-student in Florence described him to me. Pico's writings are the quintessence of Marsilio Ficino's teachings." And he recited the celebrated paragraph of Pico della Mirandola's Oratio De Hominis Dignitate:

"The Supreme Maker said: 'We have placed you at the center of the world, so that you may observe and consider all that is in the world. We have made you a creature neither of heaven nor of earth, neither mortal nor immortal, in order that you may, as the free and proud shaper, mold yourself in the form you may prefer. It will be in your power to descend to the lowest brutish forms of life; but you will be able, through your own decision, to rise again to the superior orders whose life is divine.'"

Jeroen had listened with rapt attention, and asked Jacob to repeat the quotation. He exclaimed, "You have put my deepest beliefs into words. It will be the theme of this painting. I now see a great triptych describing this New Man. The center panel is still empty. Will you teach me what should go there?"

Quietly Jacob said "Yes, I will." It would be a larger challenge than he had ever taken on as teacher. He had no experience in painting. Seeing, real or spiritual, was not his domain, his strength were words. The new aesthetic theories of the Italian Renaissance would obviously not apply here. But to become the instructor and friend of this young man would justify any effort on his part. Jeroen would supply more than enough imagination for the two of them. He recalled Pico's affiliation with Boticelli, but they were of the same mind. His relationship to Jeroen would be full of dark, completely new adventures into the unknown recesses of man's mind. And Sibylle? He soberly analyzed his attraction to her as physical, but no less there was his deep curiosity about her unstable female soul.

He

turned to Sibylle, "What would you think if I became Jeroen's

teacher?" "I often cannot put words to my visions,"

She said sweetly. "Jeroen intuitively understands me and paints

what I see. But I have to find the explanations of my visions myself.

He is not a man given to words. Being with you has opened a new

understanding of old dreams."

There remained his obligations

to Maximilian and his father Emperor Friedrich. For the time being

his livelihood depended on them. He had saved some money, Friedrich

was very generous, but he would need a job in Brabant to be near

Jeroen and Sibylle.

Jacob had left with Maximilian's entourage. Winter shrouded the country in ice and snow. Gray clouds drifted across the wide sky. Sibylle was often crying over the loss of Jacob, who had expanded her mind with such ease. She and Jeroen did not see each other often. Jeroen was kept busy in his father's shop. Several commissions had to be finished before Christmas. The drawings for the triptych of the New Man lay idle. Besides Sibylle depressed him. She was in love with Jacob, and he knew no remedy for that.

The thought of marrying Sibylle had occurred to him many times in the past, but his parents were decidedly against such a liaison. Apart from her being Jewish, their reasoning was straightforward. He was the most imaginatively gifted of his brothers. He should take over the shop. But he was, in his father's opinion, too restless and moreover sloppy at times. He could paint a panel with great speed and without any under-drawing, but his brush work was often hasty and careless, which displeased their clients as much as his revolutionary ideas. If he wanted to continue this free-style life, he better marry a well-heeled woman whose means could provide for his independence and, as his father hoped, tame his unruliness. Jeroen laughed, the first perhaps, the second never. However, he conceded that Sibylle, as much as he loved her, was not the woman who would make a suitable companion for the rest of his life. He did not feel inclined to follow Jacob's unsteady wandering life. Maybe his mind was restless, but his heart was surely conservative.

He realized that the triptych of the New Man was a grandiose plan that far exceeded anything he had worked on. He smiled thinking of his father's exhortations, but he was fully aware that to make this project a success, he had to refine his painting technique and do a carefully considered layout. He still could not see the middle or the third panel of the triptych. Jacob and he had not discussed that. Did Jacob know? Skeptical as he was, he doubted it. He talked to several people who had been to Florence, and whom he occasionally met at the illustrious "Confraternity of Our Lady", of which his father was an elected member. One or the other traveler had heard of Marsilio Ficino, the Neoplatonist, but could not put his philosophy into words. Where was Jacob? He would finish the right wing with Sibylle, the other two parts would have to wait for Jacob's return.

Jeroen took his drawings for the new triptych to his beloved sister Herberte's place, who lived with her twins, a boy and a girl, in the large house of their grandmother's in Vught. Herberte was the dark sheep in Jeroen's family. The father of her children had been black and so were the twins. Holland had proven too cold for him, and he had left her.

Sibylle and Jeroen's meetings at Herberte's were often tense. He had added a sketch of monsters attacking armored knights which would fit into the area behind the Face. Sibylle dismissed them with a shrug. The leader of the knights, stretched out on a circular disk, was being torn apart by reptiles. A knight was being hanged in a tree. Several more knights poured from a stable lantern, driven on by gnomes with spears. This scene was balanced on the edge of another of his neighbor's butcher knives. Below them, in a cave a naked man was riding on a whore, and two whimsical figures on a plank above the frozen lake were quietly discussing the mayhem.

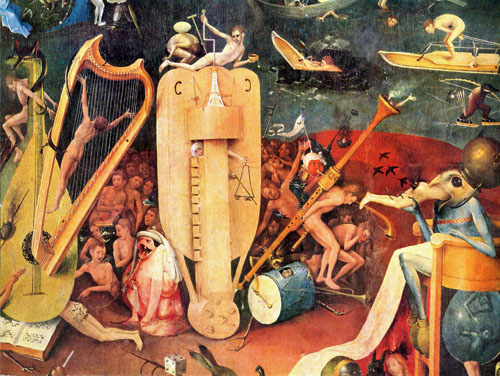

These scenes would cover the upper half of the panel. What to do with the lower half? Sibylle had a suggestion. Jeroen had long been fascinated by the obscenity of certain oversized musical instruments like the bassoon and the bag-pipe. There were already several sketches of those around. Sibylle said, "People will think that this is an ordinary rendition of hell. If you would add one of your bassoons that would show them that this is not a Christian Hell. Who has ever heard of music in hell?" Jeroen set to work. Soon a long "bombard," issuing curly smoke from its end, crossed the center of a new sheet. The bassoon was blown by a blustering man in a long-pointed night-cap. Sibylle remarked that the bassoon needed a female companion. Before her eyes Jeroen created a life-like hurdy-gurdy as tall as a house. A nude man lying on its top was turning the crank. From its sound hole a woman striking a triangle looked intensely at the beholder. Jeroen turned to Sibylle, "She is the female counterpart to the Face, the only person who makes a pure sound."

They couldn't agree on other equally ribald instruments. She left, and late that night Jeroen started over again, adding an oversized harp. Into its strings a naked man was strung. Next to it a reptilian monster had hanged a man to the neck of a giant lute. Below and between the instruments a group of naked people, led by a chimera, sang Christian hymns from notes emblazoned on the naked behind of a prostrate man. In the early morning hours Jeroen examined his drawing with pleasure.

A few weeks later Sibylle tracked him down. She was very excited. "Tonight I had a vision of the Emperor sitting on a kind of high-chair, a latrine over a sewage hole. He appeared as a bird-man devouring people, which he excreted in a amniotic sack into the hole below. At his feet sat a young pregnant woman, maybe Eva, in the spindly arms of a fox-monster, who was feeling her all over." She shook herself, the vision had been revolting, but she thought it would fit into his layout.

They went to Herberte's house and Jeroen drew her dream. He added a few details like a big fart and a flight of birds escaping from the behind of a victim the bird-man was eating. He put an inverted copper-cauldron on the emperor's head to show his empty bird-brain. He made a man and a woman issue in the amniotic sack, and below them a man vomiting into the sewer, supported by a woman. Eva in the arms of the fox-devil saw herself in a mirror covering the backside of a tree-monster, an old, favorite subject of his.

During the summer Jeroen began to paint. He carried his easel, brushes, and the mineral pigments to Herberte's house and ground and mixed the paints himself. The days were longer now, and he often worked by candle light way into the night.

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, the Burning City, 1467, Madrid

Sibylle's dream of the burning city rose in apocalyptic terror: The windows of the buildings, glowing in white heat, sent rays of light into the black sky. Following their quixotic leader the Spanish army, a frightened bunch of heavily armored soldiers, retreated across the bridge. The winged crosses of two windmills were ablaze, and naked people drowned en masse in the lake.

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, the Tree Man, 1467, Madrid

Below this skyline the scenes spun around the Tree-Man and his Face in a tight spiral driven by the visual power of the three-story-high musical instruments and the ears forever disconnected by the ominous knife of his discord with Sibylle .

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, Musical Instruments, 1467, Madrid

The ghastly blue Emperor-bird sat on his throne. In one bottom corner of the panel he added Fortuna disrobed holding on to a turned-over gaming table to which one of the players had been staked by a sting-ray shark. A crowd of shouting people demanded the resumption of their games of fortune. In the lower right corner a young member of the Knights of St. John carried a sealed ecclesiastical Bulle to be signed by a fat pig in the dress of an abbess, who was about to swindle an honest man out of his property.

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, the Emperor Bird, 1467, Madrid

Sibylle liked the additions and examined the panel. His brushstrokes were precisely controlled, the layout of the crowded painting superb. The colors and objects of the lower half created a fitting contrast to the burning city. She exclaimed cheerfully, "You have outdone yourself. The other two panels of this triptych will celebrate my wedding." Jeroen was taken aback and gloomily asked, whom she was going to marry. "Oh," she said nonchalantly, "the New Man, of course, if he ever comes back! Whom did you think of?" He had expected that, but not that she would say it so frankly. He dropped his brush. His hands hanging by his side he looked at her, tears in his eyes. He said in an defeated voice, "So this is how our friendship will end." "Nonsense," she said stroking his head. "It has just started. Look at your painting. We have never worked together like this. Jacob has opened my mind. I have been able to give names to what I see and tell you. This has never happened before." She kissed him and smiling at his saddened face said, "You may not realize that you have also become a new man. Instead of doodling monsters of your fantasies, you painted an extraordinary panel which will become a timeless masterpiece. You are revolutionizing Brabantian painting. Everyone will imitate and copy you. I love you and our friendship will remain as long as I live. Together with Jacob we will change this world to the better. I see it and believe in it like I have never believed in anything else before."

Sibylle hugged him and his tears slowly dried. Sibylle said sweetly, "My stepmother told me that to the Persians birds are symbols of the souls of men. All people have a soul-bird which reflects their personal character. Jacob's is a magpie. He knows and talks a lot and inquisitively pries into other people's minds. He may also be argumentative and jealous. Yours is a hoopoe." Jeroen looked at her mockingly and asked what a hoopoe stood for. She said cheerfully, "You see the invisible and paint what you see. You are the messenger of the other world." He smiled and said, "You always know hidden things I have never thought of. I a hoopoe?" He shook his head.

Sibylle said, "Let me tell you the Fable of the Birds which my stepmother told me. It is a Sufi teaching story which these wandering minstrels brought to Provençe from Persia."

"Once upon a time," she began, "the birds congregated to elect a king. They felt they had no aim and purpose in this world, maybe a king would give them direction. They asked the hoopoe. He told them that the name of their true king was Simurgh, but he lived far away behind seven valleys which they would have to cross to find him. It would be a perilous journey. Like you, the hoopoe made them see a vast wasteland cut by terrifying valleys where lost people were dying.

The vain Parrot was all for this journey, he longed for immortality. The Peacock wanting to become whole joined him. But the Partridge said he was content with his collection of precious stones, the Sparrow considered himself too weak and insignificant for such a labor, and the Nightingale was in love with the rose and didn't want to leave its intoxicating smell. The hoopoe showed them their conceit. The passionate attachment of the Nightingale to the rose would prevent her from recognizing the Simurgh, when she finally reached the end of the path.

They set out to cross the first Valley of the Quest, a vast stony desert. Every night some birds got lost, others died of thirst in the heat of the day. The Hoopoe told them, that only those will survive who gave themselves completely to the quest and divested themselves of all that seemed certain in their previous life: convention, dogma, religion, beliefs or unbeliefs. One night he gave the birds a vision of the beautiful realm of the Simurgh, and they flew on in their search.

The second valley, the Valley of Love they saw themselves among men and women in the fiery flames of love for each other and God. The lukewarm were consumed by the fire and perished in ecstasy. You must be free, said the Hoopoe to sacrifice your heart to the beloved or you will never grasp its secret.

This you will learn in the third Valley of Understanding, which has no end or beginning: Knowledge is useless and temporary. How many have lost their way, cried the Hoopoe, in search for one who claims to possess the knowledge of the mysteries. Once you have stripped yourself of this false goal you will become aware of the secrets, which God has hidden in your soul. There are as many different ways to cross this valley as there are different souls, but those who are sluggish or asleep will perish by the wayside.

The weak littered the path of the fourth valley, the Valley of Independence and Detachment. An icy wind so violent that it devastates the landscape of your mind, unless you can rise and detach yourself from all desire to possess your deepest longings and cravings. Nothing old or new had value here. If you survived bared of all false power you emerged like a new-born in the drop of water from which the world was created.

What was left of them was broken into a thousand pieces and then recomposed in the fifth Valley of Unity. The hoopoe made them see that the myriad of different people despite their multitude are one complete whole. He showed them that the secret of this valley was beyond words and names. The New Being, they will become, will cease to think of eternity as before and after.

The hoopoe showed them how the sixth Valley of Bewilderment and Astonishment will overcome them. There sighs will be like swords, each breath an agony of bitterness. Sorrow and lamentation will be their lot, and they will be attacked by depression and despondency. But he who has achieved unity will overcome these sorrows and himself and understand with certainty, that he knows nothing, that he is unaware of his soul, that he is in love, but knows not with whom.

The last Valley of Deprivation and Death the hoopoe could not describe, it could only be experienced. You will fall like a drop into a big ocean and cease to exist, but when you emerge from this deprivation of your senses you will become aware that you have been created a New Being who has lost its separate existence and participates in the harmony of the movements of the Ocean of his Soul, which is God.

Only thirty of the hundreds of birds who set out survived this journey of many months and years. They became aware that the Simurgh was an allegory of the ocean of their soul. By immersing themselves in the Simurgh they found joy, became part of all secrets, and died to receive immortality."

She turned to face Jeroen. "Do you think you can paint these visions for all of us to see? It will be the subject of the middle panel."

In late September a letter from Jacob arrived.

Carregi-Fiorentino, 20 August, 1467

Dear

Jeroen, beloved Sibylle!

A full year has passed since I met you,

and many things have happened. I left Friedrich's and Maximilian's

employ and moved back to Florence for the winter. Maximilian has

become increasingly engaged in the political schemes of his father.

We moved around a great deal, no time for leisurely philosophical

conversations. We separated on good terms, he will always remain a

friend and student of mine.

Marsilio

Ficino

has become the head

of the Florentine Academy. Cosimo di Medici has given him a beautiful

house in Carregi, where Marsilio has collected a congenial group of

young students. His love for them is ever present. A wonderful place

to be and discuss Plato, whose dialogues he has just finished

translating into Latin. He is now working on an extensive commentary

to Plato's "Symposium" to which each of us is encouraged to

contribute. Imagine, all about Love! We celebrated Plato's birthday

with a philosophical banquet in his spirit.

Following Plotinus,

Marsilio envisions a hierarchy through which man rises to perfection.

At the bottom are physical man, animals, and minerals. On the next

level man perfects his divine qualities until he acquires the

"rational soul" which occupies the third level. Above

resides the angelic world and finally God. Central to this universe

is a "world soul" in which all men partake and which is the

true essence of all things created by God. He is convinced that this

universe is held together by the force of love in the Platonic sense.

True love between people always involves at least three, two

individuals and God. He advocates contemplation to ascend to this

joyful state. Any person should be able to attain the ultimate goal.

The reward is immortality of the soul.

How

is Jeroen's painting coming? I have looked at many paintings. Some

painters, for example Boticelli, have tried to translate Ficino's

thoughts into images, but they don't have your power and acuity,

Jeroen. If I return to you, and I am planning to do so coming Spring,

I would like to be involved with the layout of this triptych. I spent

many days thinking about the central panel. At this time I feel it

should depict the second, third, and fourth level of Ficino's

universe. The misery of our physical world you have shown more

powerful than he, the kind man, could ever imagine ---and God is

invisible, indescribable, and unimaginable to me. He does not have a

fatherly beard and should not be shown.

There is one question

Ficino does not address, except by implication. It is death. We have

discussed Plato's "Phaedo", and Marsilio has avoided

illuminating us how man, who is both body and soul, could cope with

his fear of death, except by giving up the body and becoming all

soul. Is suicide an option? I have a hunch that a woman might know

the answer, but there isn't a woman in Ficino's circle. I am hoping

dearly that Sibylle knows. Who else could?

Another disagreement I

have with Marsilio is that he tends more and more to an all-Christian

point of view. I still am not reconciled to the idea that Christ is

the Messiah and Savior of all mankind, who facilitates and through

the Church controls our ascent to God. Marsilio is. But one must not

forget that the Church holds a powerful sway over the life of people

in Italy. They constantly search for heretics, and Ficino is closely

watched. Of course, he is a priest who is preparing to be ordained as

a canon of the Duomo in Florence next year.

I like your critical

view of Christian institutions, Jeroen. Life in Brabant is much freer

than here. I even found the canon of St. Janskerk sufficiently

open-minded to discuss this subject. Again I must listen to Sibylle

who believes in Christ, as a Jewess.

I am planning to make the

pilgrimage to Den Bosch as soon as the passes open. Maybe I could

collect a small circle of people in s'Hertogenbosch who are

interested in exploring neoplatonic ideas. Ficino's Academy is a

persuasive example. But although I have met many influential and

educated people in Brabant, I see no one who would be the equal of

Cosimo di Medici.

I am longing to be with you, my dearest

friends.

In Love.

Your

Jacob

They discussed Jacob's letter, and Sibylle pointed out that the story of the birds fitted Jacob's vision of the middle triptych. "The birds and Ficino are on the same quest, but to me the Messiah is missing, He would be able to resolve the imbalances of Ficino's universe."

Sibylle

was overwhelmed by Jacob's expectation that she would solve the

ultimate mystery of man's life. She was a young woman who had not

born children conceived in the fire of a great love. "I am not

afraid of death as you are and Jacob seems to be," she tenderly

confided to Jeroen, who did not feel strong enough to object, "but

I cannot explain why I have this certainty."

She thought

about her dilemma, and late that night told Jeroen a strange story:

"I have never told this to anybody, but when I first became a

woman my stepmother said this event had to be celebrated. She asked

me to bring a kerchief with my menstrual blood as proof, and late at

night, from a chest she had rescued from her life in Provence, she

unpacked a number of

strange

objects.

They were not large, the size of a hand, and looked very ordinary.

She first took out a white replica of a woman's breast cut by a slit.

She said the slit was the vagina and that it represented the cycle of

fertility that I was entering into. Then she brought to light two

large crocks and a smaller one and placed them on a shelf next to the

breast. They represented the family, two parents and a child between

them. On the right of the breast she set up an ibis, pulling with its

beak at the down of its chest to make a bed for its young, and an

earthenware pot, which she said was the womb of the earth. This she

explained represented the lowest level of a woman's life.

On a next higher shelf she placed a mortar with a pestle, an obscure object, which she said was a frog holding up an egg, an old, bent-over woman with a cane, a couple dancing back-to-back holding up a funnel, and another pot she called an urn. I stared at these things uncomprehending. Stepmother explained that these objects represented the secret knowledge of woman: the grinding of the male organ in a woman's crotch. The frog rising from its fertile moisture holding up the egg of the world. The woman with the cane represented woman at an advanced age. The dancing couple was fighting over the meaning of life, and the urn represented inevitable death.

She dug up one more object, an ancient oil lamp incised with a frog and a cross around which was a Greek inscription. She read it to me: 'ego eime anastatis"---I am the resurrection. I did not understand, resurrection? A frog? Stepmother explained that this lamp came from Egypt, where the frog was an ancient symbol of resurrection form the swamps of the world. She placed the lamp on a third shelf above the frog holding the egg.

Wedding at Canaa, Female Initiation Altar, copy 1570 (original 1475), Cologne

High

above this collection, which she called the 'Female Initiation

Altar', she placed a sponge under a large bell-shaped hood, saying

that in the original setup moisture from the heavenly bell and the

sponge rained down on this secret woman's world to make the new woman

fertile.

She hung the kerchief with my menstrual blood on the

altar, made me undress, and lie with my head towards the altar.

Mumbling invocations in Provençal Hebrew, she touched my

mouth, my breasts, my belly, and my crotch. At the end she bade me to

remember these symbols, saying that I was now fully initiated into

the female secrets of maternity. Next morning she took me to the

Jewish bathhouse where I had to take a purification bath under her

supervision."

Sibylle shook her head and looking at Jeroen's perplexed face asked, "Do you understand any of this? I still don't." Jeroen looking past her said, "How can I, I am a man. I will make a drawing of this altar and think about what you told me."

A few nights later he showed her his drawing. She suggested a few corrections. The objects were much cruder than he had imagined. "You should," said Jeroen, "talk to your stepmother again about death and female insights. I cannot deduce anything from this altar." She said, "If you come with me, my hoopoe, my lover, I will."

Jeroen had met Sibylle's stepmother before. On this occasion she appeared more formidable and frightening to him. She is a witch, he thought. Sibylle broached the subject by asking how, when everyone seemed scared of death, she should not feel this apprehension. "My child I am not surprised," said the woman severely, "you experienced your mother's death when you were born. People who have experienced death are not afraid of it." Sibylle, embarrassed by this explanation asked how she could teach other people this certainty. The old woman fidgeted with her answer. Eying Jeroen with suspicion she said, "You don't mean this young man?" Sibylle blushed. "Yes, but you know Jeroen since he was a small boy." With a severe voice stepmother retorted, "He still is a man. Men are to be pitied, they cannot bear children and will never understand that giving birth and dying are closely related. This experience is the great secret of women. Life is like a circle without beginning and end. A woman knows this beyond words." She glanced at Jeroen and in a sharp tone said. "Men throughout their life make up words and idle designs trying to escape this circle and go straight to heaven, where they think they will finally find peace from their nagging fear of death."

Jeroen's face had darkened. He stepped a few feet back and kept silent. On their way Sibylle said, "She suspects that we are lovers. You will never be acceptable to her as a son-in-law. But she did not tell the full truth. A woman can teach a man what she knows, if she loves him with all she has."

That night Sibylle had a dream. She was drowning in a dark ocean. A fierce wind was blowing, and she clutched her first-born child.. She knew the child was dead. She made some frustrated attempts at swimming and suddenly saw the Jeroen's great triptych with all the people loving each other. A great peace came over her. The wind died. She let loose of her body and became part of the great ocean that filled her soul.

Sibylle saw him walking down the lane between the stalls. It was Easter week, and she and Jeroen had set up their booths at the annual Spring Market. In wild abandon, crying and laughing, she ran to take Jacob into her arms. His clothes were crumpled and dusty from his long journey. With closed eyes Sibylle ran her fingers over his face. He took her hand and tenderly kissed it. A brown mongrel followed Jacob, which sat down next to him, wagging his tail. "May I introduce you to Maxi?" said Jacob pointing at the dog. "He has been my companion on this long journey."

She took him by the hand to Jeroen who embraced Jacob. "Sit down, you look tired," said Sibylle. "You must have traveled a long way." Jacob looked at the woman who had left him no peace. Her dark, loving eyes beguiled him and at the same time made him shy. Screeching and cawing a magpie landed next to them. Maxi barked ferociously at the bird and chased it away. "Ever since I have set foot on Dutch soil, I seem to be pursued by this kind of bird," said Jacob. "What do you call it?" "It was a magpie," said Sibylle with an enigmatic glance at Jeroen "The moment has passed. Maxi doesn't like the bird." They put up Jacob at Herberte's. He offered to pay for his meals. The twins were a surprise to him, but they could see, he liked Herberte.

Garden Triptych, Right Wing, Terra Nostra, 1468

They took Jacob into the room where Jeroen kept the finished painting. Jacob spellbound at first, finally said. "If the middle panel will be twice the size of this one it will be a large triptych. It is taller than I!" He stared at this hell for a long time. The burning city had turned out more frightening than he had imagined from Jeroen's drawings. He remembered the wise face of the New Man with his ironic smile. The enormous musical instruments attracted his attention. Sibylle explained that the instruments would mystify those who thought this was an ordinary Hell and said, "There is no music in Christian Hell!" Jacob nodded and said, "There is more to this. Ficino thinks that his universe is composed of heavenly harmonies and all Italian poets and painters are enamored by this Pythagorean idea. You destroyed that dream most effectively." He made a dismissive gesture and continued. "These days music has ceased to be a pleasure to God's ears. It has been degraded into a cacophony produced by obscene instruments and the hymns of liars." He shook his head. "I would have never conceived of such a fitting symbol for the depravity of our misbegotten world. How did it occur to you?" Jeroen described how Sibylle had demanded a bassoon, and how he had spent a night drawing this entire orchestra. He pointed at the woman with the triangle inside the hurdy-gurdy. "Did you notice her? The only pure sound in this world, my counterpoint to the Face." "And the blue bird on the latrine?" exclaimed Jacob. "Who is he?". Sibylle said gaily, "Isn't he ghastly? He is the Emperor of the Underworld devouring people. Another nightmare of mine." Jacob, as Jeroen had expected, liked the piggish abbess, but did not recognize the young man carrying the papal Bulle as a Knight of St. John. "Why the Order of St. John?" asked Jacob. "Well," said Jeroen, "because our Johanniters think they own spirituality and holiness."

As it grew dark Sibylle brought candles. The panel glowed in the background. Jeroen asked Jacob about his ideas for the middle panel. "In your letter you said that it should contain three levels of Ficino's speculation about the ascent of the soul." Jacob explained that he dreamed of the triptych as a teaching aid for his lectures on Ficino's interpretation of Plato. The lowest level of the central painting should show, what Ficino, borrowing from Plotinus, called the variations of 'rational love' in an idealized future world. A Platonic love, by which Ficino meant a spiritual relationship between two people and God. This did not exclude physical love, if undertaken in the right spirit. It should show how man's soul can be animated by love, how it will ennoble him and raise him to higher levels, closer to God. "I see a great garden," he described a circle with his hands, "a kind of paradise in which people purify their souls in the pursuit of loving each other. Sometimes these people appear to me like phantoms, not quite real. Like children fully grown but without guile. Having shed their worldly disguises they should all be in the nude, which will not startle you. I'll leave that to your imagination."

"And the next stage?" asked Jeroen. Jacob explained that the second level should be populated by souls with wings flying in a Pythagorean landscape, and as they ascended to the next higher level they would loose their human shapes and become winged creatures. "Call them cherubim." Said Jacob. "But you will see such winged souls much easier than I can." After some thought Jacob added, "As a Jew I cannot imagine God hovering above this world. God is invisible, not describable and should be omitted as a figure. His glory permeates all levels, which will be difficult to show, but he himself remains elusive." Jeroen nodded. He saw the beauty of the enchanted people in this painting, how could a man-made image of God surpass it? He too had doubts about showing God in a painting. The Bible explicitly forbade it. "All my life, I have seen and painted the misery of man on the cross and elsewhere. It will cost me an effort to show only man's joy and bliss. However, if I imagine these people as not being real men, not being weighted down by earthly toils and the fear of death. I can see what you describe."

Sibylle asked whether Jacob had ever heard of the Persian tale of the 'Conference of the Birds'. Jacob was astonished. He had, but only very recently. An Arabic scholar, who a few years ago had fled from Constantinople to Florence, had translated the Mantiq at Tayr, the Language of the Birds, a long poem by the Persian poet Farid ud-Din Attar and read it at Ficino's Academy. "Where did you come across this piece of Persian Sufi lore?" Sibylle explained that her Provençal stepmother had told her the story. Of course, she had not known the name of the poet. She told Jacob a shortened version of the tale and asked, "Isn't this the same quest as Ficino's? Both seem to come to very similar conclusions." Jacob shook his head and said, "Yes, of course, and Attar says it in a much more flowery language. Some of us remarked on that after the reading, but Ficino thought that Attar's a poem would not be transparent to Western audiences. But you and Jeroen, who are used to seeing winged creatures have no such problems." Jeroen showed him some sketches of birds he had made and said, "They will be very colorful and more real than the people in the painting. I think their arrival on the scene of your future paradise will be an excellent allusion to the meaning of Ficino's vision." Jacob was delighted.

Sibylle raised the difficult subject. "You wrote, that death is part of this Garden of Eden and that I as a woman might be able to enlighten you on why and how." Jacob put his head between his hands and said softly, "This is my view. In Ficino's world there is no death as we know it. His souls, as they get lighter, fly straight to heaven leaving the useless body behind. If you wish, man becomes more and more transparent by breathing in God's glory. In discussing Plato's Phaedo, the account of Socrates' death, the suspicion arose in my mind that Ficino is swayed by his all-pervasive Christian belief. To him death is powerless, and man's fear of it could be overcome by a strong faith. I doubt that and see a need for incorporating the death experience in my vision of this non-Christian paradise. We don't go straight to heaven, we have to pass a dark tunnel to the next world."

Sibylle became serious. "You are right to suspect that a woman may have a different view of Life, Love, and Death compared to a man. I have no fear of dying, but lack the experience and courage to explain why. I questioned my stepmother. She says that in giving birth, a woman can experience her death and understand intuitively that life is a closed circle. Men, who cannot have this experience must forever search for a religious or philosophical theory to calm their fear of death." Jacob raised his hands towards her and said, "You confirm one of my oldest intuitions. In Ficino's Academy there are no women, and like with the story of the birds, no one dared raise that question in earnest." He paused thinking and said, "Only now it occurs to me that Heraklitos the Greek—a man!—has left us an obscure mystical utterance: 'There is no beginning or end on the periphery of a circle.' For the first time I understand what he meant. He must have learned it from a woman." Sibylle exclaimed, "Those are the exact words my stepmother used."

Jeroen produced a bottle of wine and they drank to their reunion. Staring into his glass Jacob said, "How to incorporate death into that joyful assembly of loving people, I don't know." Sibylle looked at him. "You are not thinking of a male skeleton with a scythe, are you? He would be out of place." "No," said Jacob, "But how else can we show death? I have thought that a suicide scene might describe death, but suicide has likewise no place in this vision." Jacob took a gulp of wine and said with a laugh, "Maybe we should allow drunkenness in paradise. The Persian poets are experts at that."

Jacob grew serious again and returned to Plato. "In Phaedo Plato described in minute detail the death of Socrates by poisoning. But Socrates had been condemned to drink the poison, because he had taught the Athenian youths ways of understanding themselves, which disturbed the conventional notions of their elders. Similar things are happening again, but they should not be part of this painting." Jeroen reminded him that there were other drugs that were less poisonous and produced hallucinations which, he was sure, could reveal one's death. Jacob asked whether he had experience with that. "No," said Jeroen laughing, "I don't need drugs, my imagination is already virulent enough as is." Jacob nodded and pointedly asked, "So, what do you know about dying?" Jeroen fell silent.

Sibylle came to their rescue. Excited by a sudden inspiration she suggested, "How about depicting death as a beautiful woman, who beguiles man with her charm, love, and female knowledge?" The two men looked at each other. Jeroen guessed what she meant, but Jacob seemed confounded. A moment later, knocking his head with his fist, he said, "I am a fool, in Italian death is female, la morte, and some poets write love poems to the beautiful woman whom they will meet at death. However, in painting death is a skeleton just like here." He looked questioningly at Sibylle, who blushed deeply.

While Sibylle sailed high on Jacob's attention, Jeroen grew ever more downhearted. He locked himself into his room for hours. When they asked him what he was doing, he mumbled that he was struggling with the layout and details of the middle panel. No, he was not going to show them his work until he was sure of his version of Jacob's paradise. But the reasons for Jeroen's despair lay elsewhere. He was fighting a wild attack of jealousy. "Rational Love!" he cried to himself one night. "These two can say that easily. I am expected to paint their dreams, but how can I do that without her? She spends all her love on Jacob. I need her for this journey." He did not argue with himself about who was going to marry her. Jacob would. There his mind was clear. But the excitement of working with her in Jacob's absence was gone. His dark mood effected the whole house. Whenever he emerged his friends avoided him, feeling guilty without knowing why.

One night he drew Sibylle in her full beauty, the irreproachable personification of love and death and female knowledge. She would stand at the center of the garden. He surrounded the garden with a rose hedge, the hortus conclusus of female secrets. Its entrance would be on the right. A smaller garden with strawberry trees ante muris would receive the chosen from the hell of Our World. On its left he indicated a lake, representing the Ocean of Souls the birds were searching for. A vanguard of birds, larger than people, would arrive from the left.

Whenever he was depressed he looked at his drawing of Sibylle. It reminded him of the nights they had spent together and that consoled him. He recalled that she had said that this triptych would celebrate her wedding. Somewhere there had to be a wedding.

Garden Triptych, Central Panel, Wedding Cavalcade, 1468, Madrid

In his wounded blindness a bizarre cavalcade floated before his eyes. Dozens of male animals of all species carrying naked men circling a pool from which young women were watching the parade. Riding on a white horse the bridal pair, concealed by the red flower petals of a sweet-pea, closed the relentlessly circling riders. He had to laugh, this would startle Jacob. The pestle and the mortar in reverse! A male circle in this female paradise. Good Ficino, the Italian, would be horrified by such barbarian ribaldry desecrating his universe. Cheered he drew a second oval above the mystical garden and filled it with a fantastic ring, of, four abreast, horses, boars, bears, camels, stags, a billy goat and a unicorn, a panther and a kind of huge lizard which he had seen on a drawing brought back by a traveler from Africa.

He emerged from his seclusion laughing, and found Sibylle and Jacob engaged in an argument. Sibylle was demanding that the Messiah be given some role in the triptych and Jacob adamantly refused. Jeroen listened to them for a while. He laughed that they appeared like a fighting couple under an inverted funnel. Sibylle gave him a warning look, he wouldn't dare reveal her altar! "Listen," said Jeroen, "why such an argument. I will include Christ in the form of a fish, his old symbol. I like fish! Few will recognize him in this disguise." Ashamed by his obstinacy Jacob relented and finally praised Jeroen's cleverness. Jeroen drew the two in the ante-garden fighting each other back-to-back under a shrubbery of thorns. On top of the bush he placed an owl deep in thought.

One day Jacob noticed Herberte beating her laundry with a large wooden paddle with longer and shorter notches along its length. He recognized it at once as a calendar used in Jewish communities to remember their holidays. He asked Herberte where it came from. She had inherited it from her grandmother. He didn't tell her, what he knew, but asked whether there were other things left behind by her grandmother. Herberte waved at the furniture, most of which had been hers and then took him to the attic. She opened a big chest with her grandmother's belongings. Hidden below old clothes Jacob found a Bible printed from wood-blocks in Portugal at the beginning of the last century. It was written in Hebrew. Herberte told him that Portugal was where her paternal great-grandparents had come from. She couldn't read Portuguese and had never looked a the book. Jacob asked her permission to take it to his room, where he spent the night deciphering the difficult to read Hebrew writing. He had guessed right when he had asked Jeroen. Their grandmother was a conversa, whose parents had fled to the freedom of Brabant. Jeroen was not available, he would tell him some day. Meanwhile he kept his discovery to himself.

Vught was a small village and its tightly knit Sephardic community held together. Jacob, the foreigner, had, of course, been noticed and his comings and goings at Herberte's house were watched from behind closed curtains. His association with Sibylle, the strange, medial daughter of the man who openly defied Jewish customs and raised pigs at his house, was much talked about. One had to be careful of outsiders spying in their midst, especially if they were Jews who were not part of their group. Jacob's aloof Ashkenazi ways had made matters worse. He had never talked to any of the neighbors.

It should not have surprised anyone in the know, when one night Jacob returned in unfamiliar clothes badly beaten up. His eyes stared transported at his friends. "What has happened to you?" asked Sibylle. "You look like you have gone out of your mind." Stuttering, he told them that he had been attacked by a gang of men who had beaten him up and then taken his clothes away. They had spoken Hebrew. "As I lay by the wayside an angel appeared with clothes to cover my nakedness." His words left him. His eyes bulged, staring at some apparition they couldn't see. He began to cry. Sibylle touched his blotched, stony face with her fingertips. He passed out. Sibylle ran to get some cold water. Jeroen took a knife and cut the ill-fitting shirt to give him air. They watched him helplessly. When he finally opened his eyes he said in Hebrew, "I have seen the Messiah." Sibylle, kneeling by his side, barely caught his words.

It took Jacob a week to recover. Sibylle tenderly cared for him. She guessed that he had seen his death but kept quiet. Jacob never spoke about the experiences of this night. He was much the same and did not proclaim Christ like Saulus-Paulus had, but he never objected again to Sibylle's longing for the Messiah.

A couple of months later another incident occurred. One night a messenger came running telling them that the house of Sibylle's father was on fire. Sibylle was not with them. They knew her to be at home to celebrate Yom Kippur with her family. They rushed there in great alarm. Flames were blazing from the house. A man in the courtyard was beating one of the guests. Jacob knelt by the wayside and prayed. Screaming, Sibylle in formal Jewish dress came running from the flames, unhurt. Jacob took her into his arms. "My fear of fire and now this!" she said breathlessly. They took her to Herberte's house. When she had recovered, she told them that the arsonists had been unknown Jews, who must have resented her father's liberated ways and his affront of keeping pigs. Jacob was sure that they were the same people who had robbed and beaten him, but they all knew that the magistrate would not investigate these crimes. They were Jews.

This tragic event finally broke the spell between them. Jacob cleared the air by asking Sibylle to marry him, and at Hanukkah he was formally invited to the restored house of her father.

The oppressing clouds having been swept away, Jeroen recovered his creativity. He did not show them his drawings, but he asked Jacob about the "Pythagorean landscape" of the next level of the panel. Jacob described four crystalline structures, from which the four rivers of paradise issued. Jeroen immediately saw what they looked like. Two should be male and two female to show the unification of opposites at that stage. "Leave it to me," he said. "They will be most resplendent."

The question of the left panel was less easily resolved. Jacob wanted it to show the hieros gamos, the sacred marriage in God which signified the ultimate goal of the path. But he adamantly refused to accept God hovering above the first couple in the way the left panels of contemporary triptychs showed Adam and Eve in a Christian paradise. "Then you would have to include their Fall and Expulsion from paradise. Here Genesis does not hold. In this future paradise they will live in blissful union forever." Sibylle solved this impasse for them, by saying, "Long ago I told Jeroen that this triptych will celebrate my betrothal to you, Jacob. I want Jeroen to show Christ marrying us in this side panel." Jacob let her be, mumbling, "It will look like the creation of Eve from Adam's rib." She was unmoved. "It will add to the mystery of this triptych when people realize that it is Christ who performs this marriage not God." Jacob looked at her saying, "You are right, it should express the New Covenant created by Christ for all people, Jews and Gentiles alike, which St. Paul is talking about."

Jeroen now saw the entire triptych, but he still labored over the middle panel. The upper parts, the castles of Pythagoras and the flying souls would be easy, but the happenings around the entry, the arrangement of so many euphoric people, and the death scenes still troubled him. He had consulted a trusted pharmacist in town about hallucinatory potions. The man had offered him a box of small red pills containing refined opium imported from India. He had said that he always kept them around for another, God forbid, epidemic of the plague. This potion was the last resort of the dying. They would be freed of their pain and see the most glorious visions of the Thereafter. Jeroen bought the box and would have experimented with the pills ---Jacob's question whether he had tried drugs still nagged him ---had the pharmacist not warned him at the last moment, never to use the pills when he was depressed or alone. He didn't want to share this experiment with Jacob, and he was not sure that he wasn't still depressed.

Garden Triptych, Central Panel, Sibylle and Death in Paradise, 1468, Madrid

The idea of using fish as symbols of Christ and His resurrection appealed to him. He lovingly redrew Sibylle and placed her next to a "death" experience, which he would shimmer in all colors of the rainbow. A man was sitting in the open maw of a barrel, or was it the entrance to the tunnel to the next world Jacob had talked about? Above the gaping opening he placed a dark Barbery Duck, the one who doesn't speak. It held one of the red opium pills in its beak ready to drop it into the open mouth of the man. He redrew the sketch and placed the duck on the bent knee of a woman who was trying to make a handstand. Her head and upper body would be covered with colorful feathers: a half-complete transformation into a soul-bird. The woman like the duck could not see nor talk, but touched with one anxious hand a large fish to reassure herself of her resurrection. Jacob had told him, that in Pythagoras' world only the fully balanced people could achieve a perfect handstand. He drew another woman next to the half-finished metamorphosis who, fully plumed, stood freely balanced on her hands. He sketched in a crowd of men and women watching eagerly from behind the barrel. Imagining it in color, he looked at his drawing and saw it was good.

Were the people of this future world all beautifully young, innocent, and nubile? He shook his head. Sibylle certainly was neither innocent nor ignorant. There should also be older people, and seasoned Beghines past their prime and, he thought of Herberte's twins, black people who would find entrance to this realm. He decided that he would include a few older men as teachers and moral guardians. He laughed, bliss alone offered no guarantee for keeping this paradise in harmonious balance.

Jacob had said, making love "in the right spirit" was permitted. Right spirit? He thought of Sibylle's passion. Finally he drew an old man carrying a big, half-open, black mussel from which protruded the four legs of a couple in tight embrace. Two pearls rolled from between their legs. The man would carry his precious burden towards the lake.