Through the West African Desert to Mali

Rihla

Book 14

West Africa and Mali 1351 - 1353

Through

the West African Desert to Mali

Rihla

14, 1352

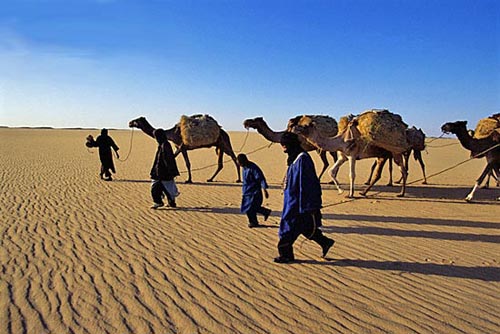

Sijilmassa -Merzouga

Ramadan

caravan at the edge of the desert

Photo werner

daehler, Panoramio

Fom

Marrakush I travelled with the suite of our master [the Sultan] to

Fez, where I took leave of our master and set out for the Negrolands.

I reached the town of Sijilmasa, a very fine town, with quantities of

excellent dates.

I stayed there with the learned Abu Muhammad

al-Bushri, the man whose brother I met in the city of Qanjanfu in

China. How strangely separated they - are !

At Sijilmasa I

bought camels and a four months' supply of forage for them. Thereupon

I set out on the 1st Muharram [February] of the year 1352 with a

caravan including, amongst others, a number of the merchants of

Sijilmasa.

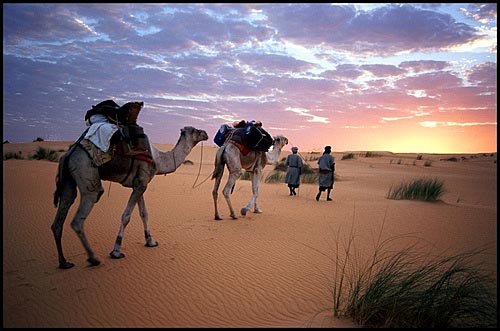

Rihla

14, 1352

Chegga

Caravan

in the the desert

Photo Michael

S. Lewis, Panoramio

From

this point a takshif is hired. The takshif is a man of the

Massufa [Berber] tribe who is hired by the persons in the caravan.

That desert is haunted by demons; if the takshif is alone,

they make sport of him and disorder his mind, so that he loses his

way and perishes. For there is no visible road or track in these

parts— nothing but sand blown hither and thither by the wind.

You see hills of sand in one place, and afterwards you will see them

moved to quite another place.

Our guide there was one who had

made the journey frequently in both directions, and who was gifted

with a quick intelligence.

I noticed, as a strange thing,

that he was blind in one eye, and diseased in the other, yet he had

the best knowledge of the road of any man. We hired the takshif on

this journey for a hundred gold mithqals, he was a man of the

Massufa.

Rihla

14, 1352

Taghaza

Salt

panning in Taghasa

Photo

muzungu03, Panoramio

Taghaza

is an abandoned town in the desert region of northern Mali. Founded

in the 10th century, it was once an important salt-mining centre,

visited by Ibn Battuta in 1352. Slaves quarried the salt in 200 lb.

blocks, which were then transported 500 miles by camel to Timbuktu

and exchanged for gold. Taghaza produced salt throughout the

fourteenth and fifteenth centuries under Berber supervision. It was

drawn into the Songhay Empire in the late 15th century.

After the

town's destruction by Moroccan forces in 1591, Taoudenni took its

place as the region's key salt producer. (Wikipedia)

After

twenty-five days we reached Taghaza, an unattractive village, with

the curious feature that its houses and mosques are built of blocks

of salt, roofed with camel skins. There are no trees, nothing but

sand. In the sand is a salt mine; they dig for the salt, and find it

in thick slabs, lying one on top of the other, as though they had

been tool-squared and laid under the surface of the earth. A camel

will carry two of these slabs.

No one lives at Taghaza except

the slaves of the Massufa [Berber] tribe, who dig for the salt; they

subsist on dates imported from Dar'a and Sijilmasa, camels' flesh,

and millet imported from the Negrolands.

The negroes use salt

as a medium of exchange, just as gold and silver is used [elsewhere];

they cut it up into pieces and pay with it. The business done at

Taghaza, for all its meanness, amounts to an enormous figure in terms

of hundredweights of gold-dust.

Rihla

12, 1351

Taoudenni

Another

Morning

Photo Philippe

Buffard, Panoramio

Water

supplies are laid in at Taghaza for the crossing of the desert which

lies beyond it, which is a ten-nights' journey with no water on the

way except on rare occasions. We indeed had the good fortune to find

water in plenty, in pools left by the rain. One day we found a pool

of sweet water between two rocky prominences. We quenched our thirst

with it and then washed our clothes.

This desert swarms with

lice, so that people wear string necklaces containing mercury, which

kills them. At that time I used to go ahead of the caravan, and when

we found a place suitable for pasturage we would graze our beasts.

We went on doing this until one of our party was lost in the

desert; after that I neither went ahead nor lagged behind. We passed

a caravan on the way and they told us that some of their party had

become separated from them. We found one of them dead under a shrub,

of the sort that grows in the sand, with his clothes on and a whip in

his hand. The water was only about a mile away from him.

Rihla

14, 1352

Tasarahia-Tichit

Shadows

in the Sand

Photo Hanson

Hosein, amistrel.tripod.com

We

came next to Tasarahia, a place of subterranean water-beds, where the

caravans halt. They stay there three days to rest, mend their

waterskins, fill them with water, and sew on them covers of

sack-cloth as a precaution against the wind.

From this point

the takshif is despatched to go ahead to Iwalatan, carrying letters

from them to their friends there, so that they may take lodgings for

them. These persons then come out a distance of four nights' journey

to meet the caravan, and bring water with them.

It often

happens that the takshif perishes in this desert, with the result

that the people of Iwalatan know nothing about the caravan, and all

or most of those who are with it perish.

Rihla

14, 1352

Iwalatan-Qualata

Houses in Qalata

Photo vincenzo

francaviglia, Panoramio

On

the night of the seventh day [from Tasarahia] we saw with joy the

fires of the party who had come out to meet us. Thus we reached the

town of Iwalatan [Walata] after a journey from Sijilmasa of two

months to a day.

Iwalatan is the northernmost province of the

negroes. When we arrived there, the merchants deposited their goods

in an open square, where the blacks undertook to guard them.

The

merchants presented themselves to then governor of Iwalatan. The

merchants remained standing in front of him while he spoke to them

through an interpreter - although they were close to him - to show

his contempt for them. It was then that I regretted of having come to

their country, because of their lack of manners and their contempt

for the whites.

Later on the mushrif [inspector] of Iwalatan

invited all those who had come with the caravan to partake of his

hospitality. At first I refused to attend, but my companions urged me

very strongly, so I went with the rest.

The repast was

served—some pounded millet mixed with a little honey and milk,

put in a half calabash shaped like a large bowl. The guests drank and

retired. I said to them " Was it for this that the black invited

us?" They answered "Yes; and it is in their opinion the

highest form of hospitality."

This convinced me that

there was no good to be hoped for from these people, and I made up my

mind to travel [back to Morocco at once] with the pilgrim caravan

from Iwalatan. Afterwards, however, I thought it bettert to go to see

the capital of their king [at Malli].

Rihla

14, 1352

Qualata, The Morals of the

Massufa

Massufa

Berbers...

My stay at Iwalatan lasted about fifty days; and I was shown honour and entertained by its inhabitants. It is an excessively hot place, and boasts a few small date-palms, in the shade of which they sow water-melons. Its water comes from underground waterbeds at that point, and there is plenty of mutton to be had. The garments of its inhabitants, most of if whom belong to the Massufa tribe, are of fine Egyptian fabrics.

...and their women.

Photos Mathilda's

Anthropology Blog

Their

women are of surpassing beauty, and are shown more respect than the

men. The slate of affairs amongst these people is indeed

extraordinary.

Their men show no signs of jealousy whatever;

no one claims descent from his father, but on the contrary from his

mother's brother. A person's heirs are his sister's sons, not his own

sons. This is a thing which I have seen nowhere in the world except

among the Indians of Malabar. But those are heathens; these people

are Muslims, punctilious in observing the hours of prayer, studying

books of law, and memorizing the Koran. Yet their women show no

bashfulness before men and do not veil themselves, though they are

assiduous in attending the prayers.

Any man who wishes to

marry one of them may do so, but they do not travel with their

husbands, and even if one desired to do so her family would not allow

her to go.

The women there have "friends" and

"companions" amongst the men outside their own families,

and the men in the same way have "companions" amongst the

women of other families. A man may go into his house and find his

wife entertaining her "companion" but he takes no objection

to it.

One day at Iwalatan I went into the qadi's house,

after asking his permission to enter, and found with him a young

woman of remarkable beauty. When I saw her I was shocked and turned

to go out, but she I laughed at me, instead of being overcome by

shame, and the qadi said to me "Why are you going out? She is my

companion." I was amazed at their conduct, for he was a

theologian and a pilgrim to boot.

Rihla

14, 1352

Karsakhu-Sokolo

The

Niger near Karsakhu

Photo Galen

Frysinger

After

leaving Zaghari we came to the great river, that is the Nile on which

stands the town of Karsakhu.

Battuta

believes the Niger

is the upper end of the Nile. He gives a long geographical

description, recounting all the sultans along its course. The

deception is made complete, because the Niger flows towards the East

in this part of Africa. It discharges in Southwestern Nigeria into

the Gulf of Guinea.

When

I decided to make the journey to Malli, which is reached in

twenty-four days from Iwalatan, if the traveller pushes on rapidly, I

hired a guide from the Massufa (for there is no necessity to travel

in a company on account of the safety of that road), and set out with

three of my companions.

A traveller in this country carries

no provisions, whether plain food or seasonings, and neither gold nor

silver. He takes nothing but pieces of salt and glass ornaments,

which the people call beads, and some aromatic goods. When he comes

to a village the womenfolk of the blacks bring out millet, milk,

chickens, pulped lotus fruit, rice, funi (a grain re-sembling mustard

seed, from which kuskus and gruel are made), and pounded haricot

beans.

Ten days after leaving Iwalatan we came to the village

of Zaghari, a large village, inhabited by negro traders called

wanjardta, along with whom live a community of whites of the Ibadi

Sect [For a description of this Islamic sect see my marker for

Nizwa in Oman]. It is from this village that millet is carried to

Iwalatan.

Rihla

14, 1352

A Crocodile

African

Crocodile

Photo Wikipedia

I saw a crocodile in this part of the Nile, close to the bank; it looked just like a small boat. One day I went down to the river to satisfy a need, and lo, one of the blacks came and stood between me and the river. I was amazed at such lack of manners and decency on his part, and spoke of it to someone or other. He answered "His purpose in doing that was solely to protect you from the crocodile, by placing himself between you and it."

Rihla

14, 1352/53

Malli -Bamako 1352/53

On

the riverbank across from Bamako

Photo

lightstalkers.org

We

arrived at Karsakhu on the river of Sansara, which is about ten miles

from Malli. It is their custom that no persons except those who have

obtained permission are allowed to enter the city. I had already

written to the white community [there] requesting them to hire a

house for me, so when I arrived at this river, I crossed by the ferry

without interference. Thus I reached the city of Malli, the capital

of the king of the blacks.

I met the qadi of Malli, 'Abd

ar-Rahman, who came to see me; he is a negro, a pilgrim, and a man of

fine character. I met also the interpreter Dugha, who is one of the

principal men among the blacks.

All these persons sent me

hospitality-gifts of food and treated me with the utmost

generosity—may God reward them for their kindnesses!

Ten

days after our arrival we ate a gruel made of a root resembling

colocasia [Taro or Elephant Ear, a leaf vegetable - in its raw form

it is toxic due to the presence of calcium oxalate, although the

toxin is destroyed by cooking], which is preferred by them to all

other dishes. We all fell ill—there were six of us—and

one of our number died. I for my part went to the morning prayer and

fainted there. I asked a certain Egyptian for a loosening remedy and

he gave me a thing called baydar, made of vegetable roots, which he

mixed with aniseed and sugar, and stirred in water. I drank it off

and vomited what I had eaten, together with a large quantity of bile.

God preserved me from death but I was ill for two months.

The

date of my arrival at Malli was the 28th of June 1352 and of my

departure from it the 12th of February 1353.

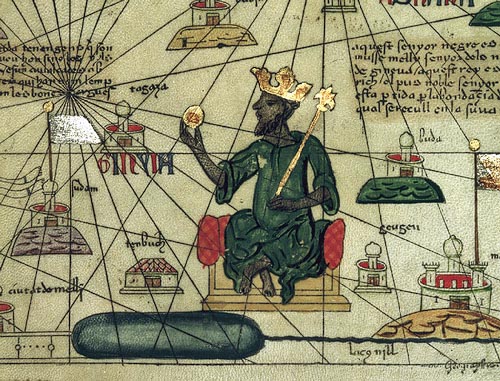

Rihla

14, 1352/53

At the court of Mansa

Sulayman 1352/53

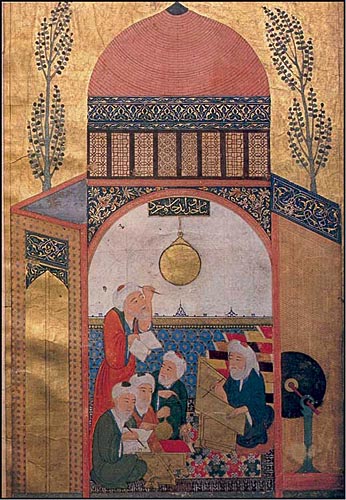

The

Mansa of Mali

Photo metmuseum.org

Mansa Sulayman's

Audiences

The sultan of Malli is Mansa

Sulayman, mansa meaning [in Mande] sultan, and Sulayman being his

proper name. He is a miserly king, not a man from whom one might hope

for a rich present.[sic!] It happened that I spent these two months

without seeing him, on account of my illness. Later on he held a

banquet to which the commanders, doctors, qadi and preacher were

invited, and I went along with them. Reading-desks were brought in,

and the Koran was read through.

When the ceremony was over I

went forward and saluted Mansa Sulayman. The qadi, the preacher, and

Ibn al-Faqih told him who I was, and he answered them in their

tongue. They said I to me " The sultan says to you ' Give thanks

to God,' so I said "Praise be to God and thanks under all

circumstances."

When I withdrew the [sultan's]

hospitality gift was sent to me. It was taken first to the qadi's

house, and the qadi sent it on with his men to Ibn al-Faqih's house.

Ibn al-Faqih came hurrying out of his house bare-footed, and entered

my room saying " Stand up; here comes the sultan's stuff and

gift to you." So I stood up thinking [since he had called it "

stuff"] that it consisted of robes of honour and money, and lo!

it was three cakes of bread, and a piece of beef fried in native oil,

and a calabash of sour curds. When I saw this I burst out laughing,

and thought it a most amazing thing that they could be so foolish and

make so much of such a paltry matter.

For two months after

this I received nothing further from the sultan, and then followed

the month of Ramadan. Meanwhile I used to go frequently to the palace

where I would salute him and sit alongside the qadi and the preacher.

I had a conversation with Dugha the interpreter, and he said "Speak

in his presence, and I shall express on your behalf what is

necessary."

I rose and stood before him and said to him:

"I have travelled through the countries of the world and have

met their kings. Here have I been four months in your country, yet

you have neither shown me hospitality, nor given me anything. What am

I to say of you before [other] rulers?" The sultan replied "I

have not seen you, and have not been told about you." The qadi

and Ibn al-Faqih rose and replied to him, saying "He has already

saluted you, and you have sent him food." Thereupon he gave

orders to set apart a house for my lodging and to pay me a daily sum

for my expenses.

Later on, on the night of the 27th of

Ramadan, he distributed a sum of money which they call the Zakdh

[alms] to the qadi, the preachers, and the doctors. He gave me a

portion along with them of thirty-three and a third mithqals, and on

my departure from Malli he bestowed on me a gift of a hundred gold

mithqals.

On certain days the sultan holds audiences in the

palace yard, where there is a platform under a tree, with three

steps; this they call the “pempi." It is carpeted with

silk and has cushions placed on it. [Over it] is raised the umbrella,

which is a sort of pavilion made of silk, surmounted by a bird in

gold, about the size of a falcon. The sultan comes out of a door in a

corner of the palace, carrying a bow in his hand and a quiver on his

back. On his head he has a golden skull-cap, bound with a gold band

which has narrow ends shaped like knives, more than a span in length.

His usual dress is a velvety red tunic, made of the European fabrics.

On reaching the pempi he stops and looks round the assembly, then

ascends it in the sedate manner of a preacher ascending a

mosque-pulpit. As he takes his seat drums, trumpets, and bugles are

sounded....

The interpreter Dugha comes with his four wives

and his slave-girls, who are about a hundred in number.

They are

wearing beautiful robes, and on their heads they have gold and silver

fillets, with gold and silver balls attached. A chair is placed for

Dugha to sit on. He plays on an instrument made of reeds, with some

small calabashes at its lower end, and chants a poem in praise of the

sultan, recalling his battles and deeds of valour. The women and

girls sing along with him and play with bows. Accompanying them are

about thirty youths, wearing red woollen tunics and white skull-caps;

each of them has his drum slung from his shoulder and beats it.

Afterwards come his boy pupils who play and turn wheels in the air,

like the natives of Sind. They show a marvellous nimble-ness and

agility in these exercises and play most cleverly with swords. Dugha

also makes a fine play with the sword....

If anyone addresses

the king and receives a reply from him, he uncovers his back and

throws dust over his head and back, for all the world like a bather

splashing himself with water. I used to wonder how it was they did

not blind themselves.

Rihla

14, 1352/53

The Character of Malli's Inhabitants

Mali

women in their compound

Photo kangatours.com

The

negroes of Malli are of all people the most submissive to their king

and the most abject in their behaviour before him. They dislike Mansa

Sulayman because of his avarice and swear by his name.

Among

their reprehensible qualities are that the women servants,

slave-girls, and young girls go about in front of every-one naked,

without a stitch of clothing on them. Women even go into the sultan's

presence naked and without coverings, and his daughters also go about

naked.

Another reprehensible practice among many of them is that

they eat carrion, dogs, and asses.

However, they also possess

some admirable qualities. They are seldom unjust, and have a greater

abhorrence of injustice than any other people. Their sultan shows no

mercy to anyone who is guilty of the least act of it. There is

complete security in their country. Neither traveller nor inhabitant

in it has anything to fear from robbers or men of violence.

Another

of their good qualities is their habit of wearing clean white

garments on Fridays. Even if a man has nothing but an old worn shirt,

he washes it and cleans it, and wears it to the Friday service. Yet

another is their zeal for learning the Koran by heart.

Rihla

14, 1353

Return from Mali

The

startling hyppopotami

Photo mamadou,

everythingspossible.wordpress.com

We

came to a wide channel which flows out of the Nile and can only be

crossed in boats. The place is infested with mosquitoes, and no one

can pass that way except by night.

We reached the channel three

or four hours after nightfall on a moon-lit night. On reaching it I

saw sixteen beasts with enormous bodies, and marvelled at them,

taking them to be elephants, of which there are many in that country.

Afterwards I saw that they had gone into the river, so I said

to Abu Bakr "What kind of animals are these?" He replied:

"They are hippopotami which have come out to pasture ashore."

They are bulkier than horses, have manes and tails, and their heads

are like horses' heads, but their feet like elephants feet.

I

saw these hippopotami again when we sailed down the Nile from Tumbukt

to Gawgaw. They were swimming in the water, and lifting their heads

and blowing. The men in the boat were afraid of them and kept close

to the bank in case the hippo-potami should sink them.

They

have a cunning method of catching these hippopotami. They use spears

with a hole bored in them, through which strong cords are passed. The

spear is thrown at one of the animals, and if it strikes its leg or

neck it goes right through it. Then they pull on the rope until the

beast is brought to the bank, kill it and eat its flesh. Along the

bank there are quantities of hippopotamus bones.

Rihla

14, 1353

Return from Mali: Segou

Sunset

on the River Niger

Photo iursound,

Panoramio

We

halted near this channel at a large village, which had as governor a

negro, a pilgrim, and man of fine character, named Farba Magha. He

was one of the negroes who made the pilgrimage in the company of

Sultan Mansa Musa [father of present Mansa].

Farba Magha told

me that when Mansa Musa came to this channel, he had with him a qadi,

a white man. This qadi attempted to make away with four thousand

mithqals and the sultan, on learning of it, exiled him to the country

of the heathen cannibals. He lived among them for four years, at the

end of which the sultan sent him back to his own country. The reason

why the heathens did not eat him was that he was white, for they say

that the white is indigestible because he is not " ripe,"

whereas the black man is " ripe" in their opinion.

Sultan

Mansa Sulayman was visited by a party of these negro cannibals,

including one of their amirs. They have a custom of wearing in their

ears large pendants, each pendant having an opening of half a span.

They wrap themselves in silk mantles, and in their country there is a

gold mine.

The sultan received them with honour, and gave

them as his hospitality gift a servant, a negress. They killed and

ate her, and having smeared their faces and hands with her blood came

to the sultan to thank him.

Someone told me that they say

that the choicest parts of women's' flesh are the palm of the hand

and the breast.

This hearsay tale may

have been connected with the mysterious Dogon people who live off

Battuta's tracks to the east. The Dogan

have mined iron and possibly gold since prehistoric times. The

canibal tale may have been invented to scare people from going to

that region.

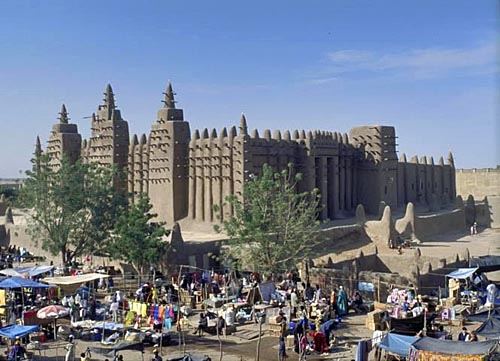

Rihla

14, 1353

Return from Mali: Segou,

Djenne

The

Great Mosque of Djenne

Photo manolosonamission.com

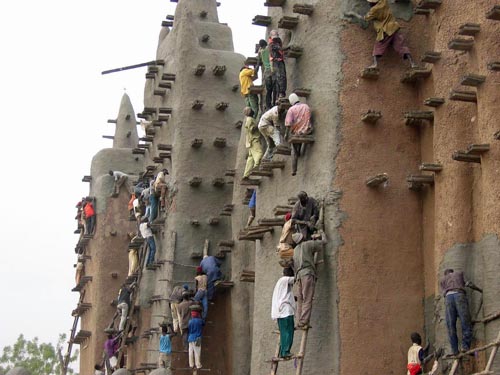

Rihla

14, 1353

Mopti

The

annual re-mudding of the Great Mosque of Mopti

Photo

visitgaomali.com

The mosque is almost entirely built in banco (raw earth). The mosque's maintenance consists mainly of repairing the mud rendering. The sticks serve as scaffolding for this annual renewal of its outside.

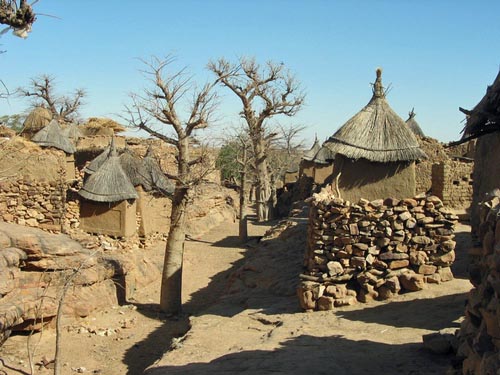

The

mysterious Dogon Villages

Dogon

Village of Dourou

Photo coolgarey,

Panoramio

Rihla

14, 1353

Korienze

The

Mosque of Korienze

Photo Sebastian

Schutyser, Archnet.com

Rihla

14, 1353

Timbuktu

East

façade and rooftop minaret of Djingareyber Mosque the oldest

mosque in Timbuktu.

Photo Archnet.org

Tumbuktu

stands four miles from the river. Most of its inhabitants are of the

Massufa tribe. In this town is a mosque built by the meritorious poet

Abu Ishaq as-Sahili of Gharnata [Granada].

Born in Granada,

Andalusia (Muslim Spain), Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Sahili studied the

arts and law in his native land. Al-Sahili gained a reputation as a

man of letters and an eloquent poet in Andalusia.

In

1324 al-Sahili met the ruler of Mali, Mansa Musa, during his

pilgrimage to Mecca. According to the chronicler, Mansa Musa was so

delighted by the poetry and narrative talents of al-Sahili that he

invited him to Mali. Al- Sahili settled in the growing intellectual

and commercial center of Timbuktu, where he built an audience chamber

for Mansa Musa.

So impressed was Musa that he engaged the

Andalusian to construct his new residence and the Great Djingereyber

Mosque in Timbuktu. While the residence has been lost to time, the

Great Mosque still stands in Timbuktu. (Wikipedia)

An example for

the accuracy of Battuta's information.

Rihla

14, 1353

Sailing down the Niger

Sailing

down the Nile [aka. the Niger!] in a barga. Notice the sail's

rigging.

Photo Dottor

Topy, Panoramio

From Tumbuktu I sailed down the Nile on a small boat, hollowed out of a single piece of wood. We used to go ashore every night at the villages and buy whatever we needed in the way of meat and butter in exchange for salt, spices, and glass beads.

Rihla

14, 1353

Gao

Drying

laundry on the banks of the Niger

Photo mamadou,

everythingspossible.wordpress.com

Eventually I reached Gawgaw [Gao], which is a large city on the Nile [Niger], and one of the finest towns in the Negrolands. It is also one of their biggest and best-provisioned towns, with rice in plenty, milk, and fish, and there is a species of cucumber there called inani which has no equal. The buying and selling by its inhabitants is done with cowry-shells, the same as at Malli. I stayed there about a month, and then set out in the direction of Tagadda by land with a large caravan of merchants from Ghadamas.

Rihla

14, 1353

Taggada-Tegguiada

Pulling

water from a well

Photo saharanvibe.blogspot.com

We

now entered the territory of the Bardama, who are another tribe of

Berbers. No caravan can travel [through their country] without a

guarantee of their protection, and for this purpose a woman's

guarantee is of more value than a man's.

The houses at

Tagadda are built of red stone, and its water runs by a copper mines,

so that both its colour and taste are affected. The inhabitants of

Tagadda have no occupation except trade. They travel to Egypt every

year, and import quantities of all the fine fabrics to be had there

and of other Egyptian wares. They live in luxury and ease, and vie

with one another in regard to the number of their slaves and

serving-women.

Their women are the most perfect in beauty and

the most shapely in figure of all women, of a pure white colour and

very stout; nowhere in the world have I seen any who equal them in

stoutness. They never sell their educated female slaves, or but

rarely and at a high price. When I arrived at Tagadda I wished to buy

an educated female slave, but could not find one. After a while the

qadi sent me one who belonged to a friend of his, and I bought her

for twenty-five mithqals. Later on her master regretted having sold

her and wished to have the sale rescinded.

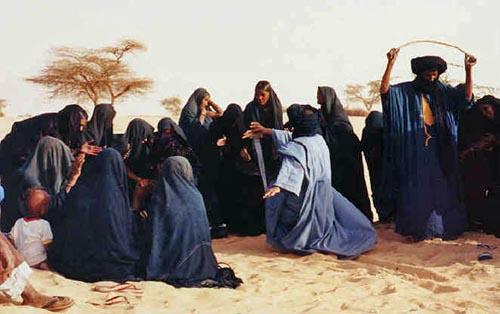

Rihla

14, 1352

Izar's encampment

Dancing

the takamba

Photos Galen

Frysinger

I

wished to meet the sultan, who is a Berber called Izar, who was then

at a place a day's journey from the town. So I hired a guide, and set

out thither. He was informed of my coming and came to see me, riding

a horse without a saddle, as is their custom. In place of a saddle he

had a gorgeous saddle-cloth, and he was wearing a cloak, trousers,

and turban, all in blue. With him were his sister's sons, who are the

heirs to his kingdom.

He had me lodged in one of the tents of

the Yanatibun, who are royal guards, and sent me a sheep roasted on a

spit and a wooden bowl of cows' milk.

Near us was the tent of his

mother and his sister; they came to visit us and saluted us, and his

mother used to send us milk after the time of evening-prayer, which

is their milking time. They drink it at that time and again in early

morning, but of cereal foods they neither eat nor know.

I

stayed with them six days, and every day received two roasted rams

from the sultan, one in the morning and one in the evening. He also

presented me with a she-camel and with ten mithqals of gold. Then I

took leave of him and returned to Tagadda.

Rihla

14, 1353

Tamarasset, Crossroads of

Sahara Routes

I

left Tagadda in September 1353 wlth a large caravan which included

six hundred women slaves. We came to Kahir, where there are abundant

pasturages, and thence entered an uninhabited and waterless desert,

extending for three days march.

We journeyed next for fifteen

days through a desert which, though uninhabited, contains

water-points, and reached the place at which the Ghat road, leading

to Egypt, and the Tawat road divide. Here there are subterranean

water-beds which flow over iron; if a piece of white cloth is washed

in this water it turns black.

Ten days after leaving this

point we came to the country of Haggar, who are a tribe of Berbers;

they wear face veils and are a rascally lot. We encountered one of

their chiefs, who held up the caravan until they paid him an

indemnity of pieces of cloth and other goods.

Our arrival in

their country fell in the month of Ramadan, during which they make no

raiding expeditions and do not molest caravans. Even their robbers,

if they find goods on the road during Ramadan, do not touch them.

This is the custom of all the Berbers along this route.

We

continued to travel through the country of Haggar for a month; it has

few plants, is very stony, and the road through it is bad.

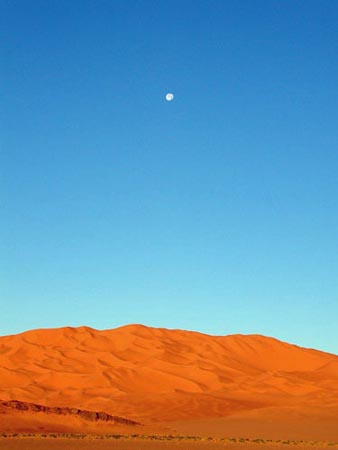

Rihla

14, 1353

Buda-Ain

Salah

The

Moon at Sunrise near Ain Salah

Photo Nabil

Benmoussa, Panoramio

We

came next to Buda, one of the principal villages of Tawat. The soil

there is all sand and saltmarsh; there are dates, but they are not

good, though the local inhabitants prefer them to the dates of

Sijilmasa. There are no crops there, nor butter, nor olive oil; all

these things have to be imported from the Maghrib.

The food

of its inhabitants consists of dates and locusts, for there are

quantities of locusts in their country; they store them just like

dates and use them as food.

They go out to catch the locusts

before sunrise, for at that hour they cannot fly on account of the

cold.

Rihla

14, 1353

Dar at-Tama on the return

Winter 1353

Ruins of

Dar-at-Tama, 1950 m high

Photo pera,

Panoramio

I set out from Sijilmasa on 29th December 1353, at a time of intense cold, and snow fell very heavily on the way. I have in my life seen bad roads and quantities of snow, at Bukhara and Samarqand, in Khurasan, and the lands of the Turks, but never have I seen anything worse than the road of Umm Junayba. On the eve of the Festival we reached Dar at-Tama. I stayed there during the day of the feast and then went on.

Rihla

14, 1353

Fez 1353-55

Writing

the Rihla

Photo scienceinschool.org

I

arrived at the royal city of Fa's [Fez], the capital of our master

the Commander of the Faithful (may God strengthen him), where I

kissed his beneficent hand and was privileged to behold his gracious

countenance. I settled down under the wing of his bounty after my

long journey. May God Most High recompense him for the abundant

favours and ample benefits which he has bestowed on me; may He

prolong his days and spare him to the Muslims for many years to

come.

Here ends the travel-narrative entitled la Rihla, a

Gift to those interested in the Curiosities of the Cities and Marvels

of the Ways of the World. Its dictation was finished on the 9th of

December 1355. Praise be to God, and peace to His creatures whom He

hath chosen.