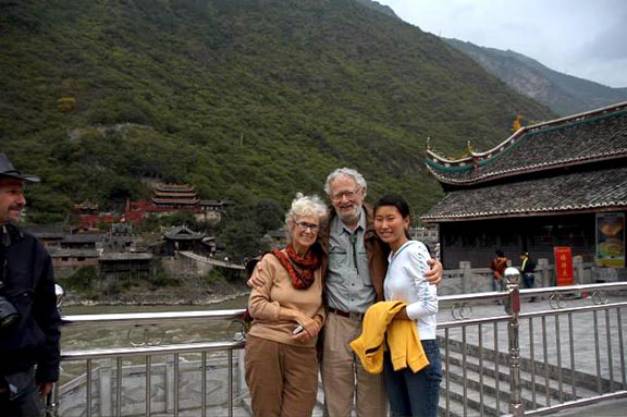

Eva, Alan, and Marty teaching in China 2006

Chengdu

First

impressions of Chengdu....more cars, the bike lanes quite narrowed from two

years ago. Heavy, heavy thick air, like a hand pressing against the chest,

going uphill on a level street. Numerous Starbuck’s with US prices, with bright

energetic Chinese smart young things making deals. The quick pulse of

capitalism; a fancy Japanese hotel and restaurant with a ‘personal chef

advisor’ (A Canadian married to a Chinese woman) to steer us through the menu.

Two large Buddhist temples with devoted worshipers, tourists, vegetarians, and

tea drinkers. I remember being surprised in 2004 to see that Buddhism was being

practiced: but then, many of the images I had of China don’t fit the current

reality. Soon, as we began teaching, we learned how radically family life is

changing.

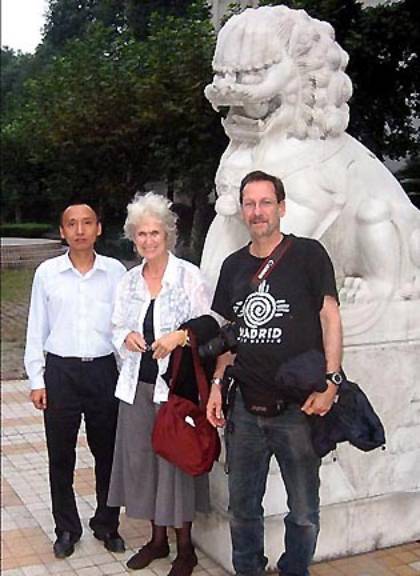

Prof. Nima, Eva, and Martin

Alan and Prof Nima

Perhaps

you will recall that Marty and I had taught for Professor Nima at Sichuan University for an afternoon at the end of

our trip in 2004. We had our students sit in a circle and, after asking them to

pretend to be our ‘California’ students, we taught them to respond as our

students at home would, participating, interrupting, expressing feelings, a far

cry from the usual classroom scene in China, where the professor speaks and the

students are there to write down every word. When we asked for a scene from

their lives, they wanted to work on the problem of the wife and mother who also

has to work. They participated

freely—in two family sculptures’, one depicting a boy who avoided school

because he felt he had to protect his mother from her abusive husband, and one

evoking the plight of a modern working mother being pulled in all directions by

her baby, mother-in-law, boss, best girlfriend, and lastly, her husband.

Each roleplayer tied a rope around her waist and tugged as hard as

she/he could. The students volunteered eagerly and participated fully,

empathizing with her plight and making suggestions as to how she might lighten

her load.

Eva, Alan, and Marty

Despite

this success which led to our being asked to return, I must confess that I was

fretful in anticipating how the teaching would actually go. I had brought

the DVD of ‘Yi Yi’ a Chinese film in Mandarin that I thought could be the

springboard for discussion if all else failed....Oh foolish Alan! No need, no

need, no need. Eva has attained a level of confidence and skill that guaranteed

from the start that the work would be deep, engrossing and heartfelt. The

story of the boy who wasn’t sure about his “flowering” proved to be a leitmotif

throughout the week. Further, the

students all had enough stories of their own families’ life for a year’s

teaching.

So,

imagine a large room, emptied of tables with chairs around the periphery.

Twenty to forty graduate students in a circle. Average age 24, many from rural

villages on scholarships, Most with 7 years of English writing and reading (

and little or no practice in speaking), a gifted translator, Tracy, and the

three of us.

Our

class was populated by graduate students from the psychology and education

departments. Just as at home, the ratio

of men to women was highly skewed.

After

a few group warm-ups which were enthusiastically embraced by the group, we

began by enacting the story I had liked

so much about the boy in Lhasa: One of

the professors had told us a story of an 8 year old boy he had met in Llasa

where he and his family had arrived that day after climbing and kow-towing all

the way for hundreds of miles. The boy told him that his father said that the

merit from this walk was his own flowering. "You can become the very

flower you were meant to be," he said, and the boy added, with a worried

look, "but I don't know what kind of flower I will be!"

To

our delight, Professor Shao Lin volunteered to play the boy, and, to much

laughter, decided to call him “little Nima.” He told the visiting professor (as

we enacted the scene) that he hated kow-towing, that he was tired, and didn’t

even want to become a flower.

Prof. Shaolin

He

wanted to be an eagle, it turned out. It was a sweet scene, with his

role-played mother giving him encouragement and praising him for his

achievement and the father speaking about the importance of buddhist practices

and family tradition—two themes fast disappearing from Chinese culture. As the

students shared their reactions after the scene, it seemed clear that only one

or two empathized with the father. They wanted to be eagles, all of them, and

fly to an American life style with plenty of American freedoms and goods.

First:

a word about family sculptures , because they were to form the basis of our

work for the week. Invented in England, this exercise was used and developed by

Virginia Satir, one of the first and most influential family therapists on the

West Coast. The directions are simple. “I would like you to take the members of

your family (or group) and sculpt them in such a way so that, looking at the

sculpture as I might be if I were passing it in a park, I’d understand

something important about this family.” The sculptor is instructed to use as

few words as possible, and the group or family members are asked to be as pliable

as they can be—like clay, or playdough.The technique is generous: it can be

extended in many ways: sculpt the ideal family, sculpt the family in the worst

of times, sculpt the part of the group that annoys you, etc.

In

our first class we asked students to

form groups of four or five and select a situation from their family lives or

from that of close friends or neighbors that they could sculpt and show to the

rest of the class. The stories varied tremendously—beginning with amusing,

somewhat superficial conflicts---such as the one titled, “How to become a bad

boy,” about one who refused to go to school and stole money from his

grandmother to treat his friends, or the one about the mother who saved her

money so she could send her daughter to Japan to get facialplastic surgery in

order to attract a rich man.

As

time went on, more upsetting themes appeared. A common one was the loneliness

of growing up in the care of a resentful grandmother under the one-child rule.

So often, there was not another child of the same age near enough to play with.

The stories of a four-year old girl who was lured to a neighbor’s house with

the promise of a pear was most upsetting—she was raped—and while justice was

served with the arrest of the man, the story followed her and marked her as a

bad girl even in Kindergarten. We all responded to the story’s pathos, but the

outcome was that she was enraged against men, whom she kicked around joyfully

as the scene unfolded. (Better in a psychodrama

than in real life!) All of the stories were sculpted, titled, and viewed by the

whole class. Then, one by one, we sculpted them again and developed the scenes

into psychodramas, of which I will describe one in detail next time so you have an idea of what went

on.

Sue's Story

I changed her name, but it's worth noting that many of the

studens had both Chinese and English names.

Sue surprised us all by saying she wanted to sculpt her family herself, with no

help from the professors. I (Eva) pretended to leave the room in an exaggerated

show of not being needed any more--but it turned out I was, after all. Her

story was about her mother and herself. Widowed a few years ago, her mother had

remarried a man who was blatantly unfaithful to her. Sue was made the

go-between, sent by her mother to bring him home from his mistress' house. He

refused, saying that if his wife found the situation so difficult, he'd just

head south with his mistress. Sue's compassion for her mother moved all of us;

her sorrow at being able only to deliver bad news was touching. While these

scenes were unfolding, Alan saw that there was another character in this scene,

one who hadn't been sculpted. Using a red velvet drape that had hidden some

equipment in the classroom, he placed it in the scene, saying, "This is

your dead father --he needs to be addressed." As he did this, Sue started

to weep and I went to put an arm around her shoulder, letting her collapse on

me. "Let's go talk to him, " I said, and we both knelt at his feet.

here Sue is looking at Alan who had asked her to pick someone to represent her

father, and explains to her that she may have some feelings to share with him.

Sue has just recovered from her deep sobs, and we go to address her father.

There are no photos of Sue's grief, either

sobbing in the beginning, or quietly weeping at my side as we sat at her

father's feet. My guess is that the photographer was either personally to moved

to shoot, or felt that the moment was too intimate. Sue later told us that she

had felt sad before, but never expressed her grief as fully.

She sat with me --squatted, really

--and told her father how much she missed him, how much her mother needed him,

and how shocked they all were by his sudden death. After this conversation had

gone on a while --I had her role-reversing with her father, of course, and he

told her how sorry he was to have caused her so much pain, how he hadn't known

he was going to die, either--I was wondering how long I could still squat there

with her and, hoping for some lessening of her grief, asked her to tell her

father what she would remember about him, to describe how he was still with

her, in her memory, her imagination, mind and dreams. Speaking as her father

through role reversal, Sue had him say the words she longed to hear, "You

have done the best you could for your mother and your family. You couldn't fix

that all by yourself. I love you and I know you were loyal to me, even though

you were helping mother with her second husband. You seem to think you have done

something wrong, but you haven't. The shame that came to the family is not your

fault.”

As she exchanged stories with him

(role-reversing again) about some of the happy times they had had as a family,

going on picnics, playing behind their house, she began to recover her

composure, allowing her to say another good-bye, and to leave the scene (which

allowed her ancient director to stand up again, much relieved but for less

lofty reasons). Because the theme of losing parents --mostly to go to work and leave

them with their grandmothers--was so common in this group, there was a

unanimous empathy during this scene and Sue, who had been rather peripheral to

the group so far, took a central place as people shared their own deep

reactions after the enactment was over. The next day, we were all delighted and

surprised. She looked so different: transformed, from a serious,somewhat

remote, rather dour person to an open, joyful one. She had isolated herself

with her pain. Having shared it, taken a long step in the journey of grieving,

she was clearly relieved and able to join the class in a new and much more

lively way.

Next: we left the campus to tour the Danba region (part of the 'autonomous'

Tibetan area) with Professors Nima, Shaolin, our videographer, Professor

Buqiong (another Tibetan), Yishi, a Tibetan friend of Nima's, Anthropology

Professor David Burnett and his wife Anne who is teaching English in Chengdu,

Mr.Zhao Xingmin (A Chinese official of some sort whose role never became clear)

and a few students: Mary and Lily, our honorary granddaughters, Summer, the

glamor girl of our trip, Jimmy, a budding businessman pretending to want to be

a teacher, and Carrick, another excellent English speaker and Tom, a psychology

student.

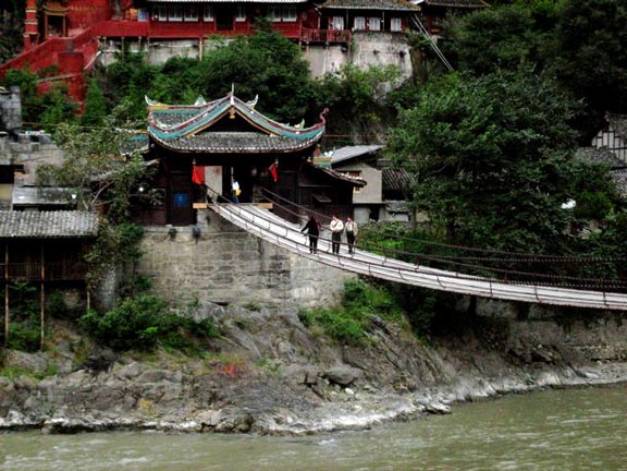

Trip to Luding and

Danba

For two years I (Alan) had wanted

to show Eva some of the Tibetan world that Marty and I had explored in 2004.

The chance to teach together in Chengdu put us within 8 hours of Kham, the

eastern realm of Tibet. Marty had hired a car and guide and was to go with

another couple deep into Kham for three weeks. On the last trip I was

struggling with oxygen deprivation much of the time: the long days of bad roads

and high altitude of Marty’s trip were out of reach.

Professor Nima offered the perfect solution. He planned to

visit a number of Tibetan farming villages at lower elevations to check up on a

number of projects he had started whose purpose was the preservation of local

culture. Would we like to go with him on a week of travel with Danba as home

base? We would go with an anthropologist and his wife,David and Anne

Burnett, Professor Shaolin, several of our Chinese students and two

Tibetan graduate students. YES! Here are Eva's photos and descriptions of that

trip.

Dr.

Nima's intent, in bringing the Chinese students on this trip was to aquaint

them with the Tibetan way of life before it disappears, to encourage them to

help in the effort to preserve this culture. There were many stories of his own

upbringing in the area. Coming from a noble family now scattered and imprisoned

by the communists, he started out in a village in the Danba area,and

worked his way up. First he worked as a messenger for the road crews, than he

worked on the road crew--long, hard days with pay that was almost nonexistent.

He loved to read and showed us the mountain paths he used to travel and the

rocks, in the middle of the river, that held him as he lay there, reading in the sun. In the

villages, he and our hosts and

his informants lectured the students on village festivals, dances,songs, school

life, agriculture and the changes being brought

about by the Chinese government which is mining the entire area, building roads

and hotels and getting ready for tourism. The climax --not attended by us for

obvious reasons--was a hike during which they had to cross a wild river on a

rope bridge, The students were still shaking with remembered fear and

excitement when they told us about it.

Our trusty jeep that took us up

into the Kham Tibetan area-- as we waited to board our vehicle, huge televised

messages appeared on one of the gigantic screens seen here and there on the

campus. "it is 8:45, classes begin in l5 minutes. Hard work means good

jobs. Work hard and achieve!"

The Luding bridge, sometimes

called the Red Army bridge because the 8th Red Army men with machine guns

crossed it and destroyed parts of the town and some of its citizens as they

marched against Chiang Kai Chek I

believe this is the Yamuna Cher river which we followed up into the mountains.

Leaving Cheng Du meant driving on a good road (oh, the illusion that this would

last!) past factory after smog producing factory, small rice and vegetable

farms, and finally, misty mountains and forests.

Some of

the people of Luding and Danba wear modern clothes.

A

typical Danba alley way -- our restaurant was midway up these stairs.

Some of you have asked what we ate --so here it goes: In

Cheng Du, we were well fed in the Foreign Experts Center--sweet and sour pork,

eggs scrambled with tomatoes and onions, chicken and mushrooms, speaking of

which we ate a lot of tree fungi, quite delicious, like black mushrooms but

more delicate--lots of noodles and rice. In the Tibetan area, food

was less familiar. First of all, at every meal and in between is Chai,

the Tibetan tea fortified with tsampa flour and yak butter, the latter usually

rancid. Having got quite ill after tasting some in a Bhutan monastery, I

quickly learned to ask for Chinese tea, which is always available. Breakfast is

a thin gruel, tea, yoghurt, and various noodle, pork and rice dishes made with

hot peppers. Luckily, Alan had foreseen my inability to eat any of this and

brought instant oatmeal which served us very nicely. In the evening, a similiar

meal would be served with many more dishes—momos (noodles filled with meat),

yoghurt, rice, noodles with pork, peanuts,

intestine meat with peppers and other greens. Our hosts were kind enough to

make a small amount of food without the stinging peppers for me.

We

always had enough to eat and the fare was very hearty. Since the Tibetans

seldom eat lunch, I learned to stock up with yoghurt, crackers, and apples for

the mid day. Two customs that surprised me were the lack of ceremony at Chinese

meals. It startling to see people throwing leftovers on the floor, for instance,

and that one is expected to leave the table as soon as the last bite is

swallowed, with almost no comment. Presented with farewell presents, our

students accepted them silently. Even the more formal ceremonies seemed to be

on their way out. A visiting official is met at the border.He is presented with

the usual white scarves, which he puts on, takes off, and gives to his

assistant who wads them up and throwns them into the car. It seems to me the

Chinese are practical --they see to their own and others' needs with great

efficiency--but in our group some of the finer points of social intercouse

seemed often to be missing.

Driving up this river which is

lined with mountains , we were surprised to learn that these hills are

completely undermined—literally -- by tunnels

made to mine the metal ore. We entered one of them--our driver, Dr.

Nima, looking for a short cut-- quickly got lost in the vast, electrically lit

cave that had pathways and exits going in several directions so that we had to

retrace our steps to get out again! "First time I ever got lost in a

cave," said Anne Burnett.

Alan climbing up to our bedroom at our host’s house. .

Children of Danba

Our Last Trip with Dr. Nima

These photos of the high Tibetan mountains and the

Tibetan plateau illustrate the last of our trips with Dr. Nima and our

students.

Still in our three cars, we went back to Danba and then started for the highest

mountain passes --12,500 feet-- and the grasslands above them. Going up the

Chao Jin River Valley (it means following the sheep's path), we drove along the

wild, white river flanked by forests in autumnal reds and yellows. The golden

Aspen, the red grape vines and then--the first look at Gunga Mountain, the

highest peak in the area! Ir can't be described. The intense blue reveals a sky

never seen before and the mountain, surrounded by the whitest of cumulous

clouds...The phrase,"the roof of the world'" makes sense to us now.

Alan surprised us all on this part of the trek, where he had needed oxygen 2

years before and felt quite uncomfortable. This year, Nima and the students

were ready with more oxygen and Alan, who had had 2 carotid stents placed

barely a month before, didn't need any! He felt just fine! So, hats off to

modern medical engineering!

Alan at 12500 ft!

Eva and Alan

triumphant at the top of the pass

These mountains are stark, high, and very cold. The peaks are above 20,000

ft.No one lives at the upper altitudes, but nomads pass there with their herds

of sheep, horses, and yaks.

Every mountain is a testimonial to the spiritual life of the people who string white and colored silk scarves up to the highest peaks, build monasteries, and create chortens and small shrines with mani stones in special places. The people were friendly and stopped us to converse in sign language and (translated) Tibetan. There was no begging.

|

|

|

A Holy woman or warrior?

Sadly enough, with the impact of the train from Cheng Du to

Llasa, and many more routes planned to make access easier, the remoteness of

this area is lessening, and yet another dignified, spiritual way of life

threatened by tourism, seen as the main attraction of this area by the Chinese

occupiers.

On the other side of the passes: a whole new world.

The grasslands --wide expanses of green hills dotted with

hundreds of yaks and ponies--ringed by more snowy peaks, where Eva rode one of

the Tagung ponies decked out in the brightest colors: saddle blankets and

bridles glowing with bright colored wools. The ponies give you a smooth, easy

ride with a single-foot gait.

If I hadn't run

out of breath at 10,000 feet I could have stayed on this pony all day.

Two Khampa ladies on

horses. They almost ran me over.

Our last days took us to the trading town of Song Du Chao, a mountain trading town

where incredibly handsome, bejeweled Khampas haggled over produce, played

billiards, bought huge sides of yak, yak fur & skins and materials to make

their clothes.

A Khampa Beauty

Much toing and froing and lots of laughter, a solid, cheerful

group Coming down was a real comedown.

Buying-out a yoghurt seller

One of the worst roads I've ever been on, rivaling

Dharamsala in India, over washboard roads filled with mad drivers who insisted

on passing on the zig-zag curves that lead us to the Kanding peaks.

Our trip ended in the town of Kanding. First, a farewell lunch in a

traditional restaurant (built for the

tourist trade which is Chinese at this point) watched over by Mao and Co. --

Kanding is a lovely town, at about seven thousand feet -- lots of Chinese

tourists, shops, restaurants, a lovely river -- but our group was still

experiencing some chest pains from the passes -- so we left happily.

Back

in ChengDu

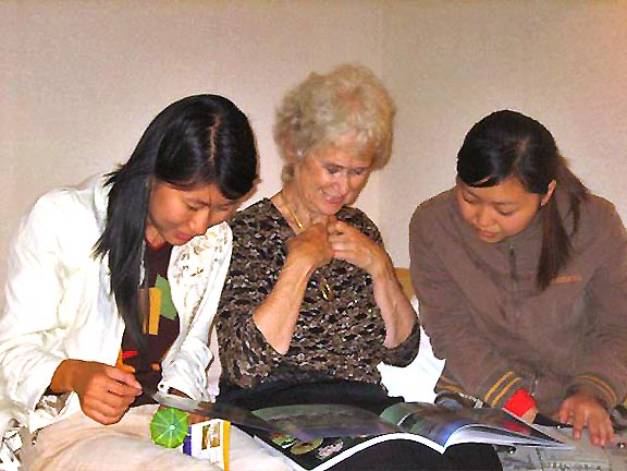

Eva and her “Granddaughters” looking over pictures from Kham.

Our farewells were sad. Our 'granddaughters' Lilly and Mary had taken such good

care of us. Now they wanted to take us out for a last hot-pot dinner and,

though we knew they couldn't afford it, insisted on paying. They declared this

quite dramatically and then managed to slip the bill to Alan who, of course,

paid it happily thanking them loudly. Always carrying their English

dictionaries, they helped us eat, do laundry, shop, going out in the rain to

get us water--very dear. We thanked them by inviting them for a last meal at

"Grandma's Kitchen" the Western restaurant in Cheng Du. They shyly

asked us to teach them how to use a soup spoon and a fork. They live in the

university and had actually never been to the city --the university is on the outskirts,

I don't know whether it's their natural conservatism, lack of cash, or why they

wouldn't chance the bus ride to a new adventure. We had all got to know each

other on this excursion, learned a lot, enjoyed ourselves immensely, and

apparently introduced them to some new ways of teaching and learning.